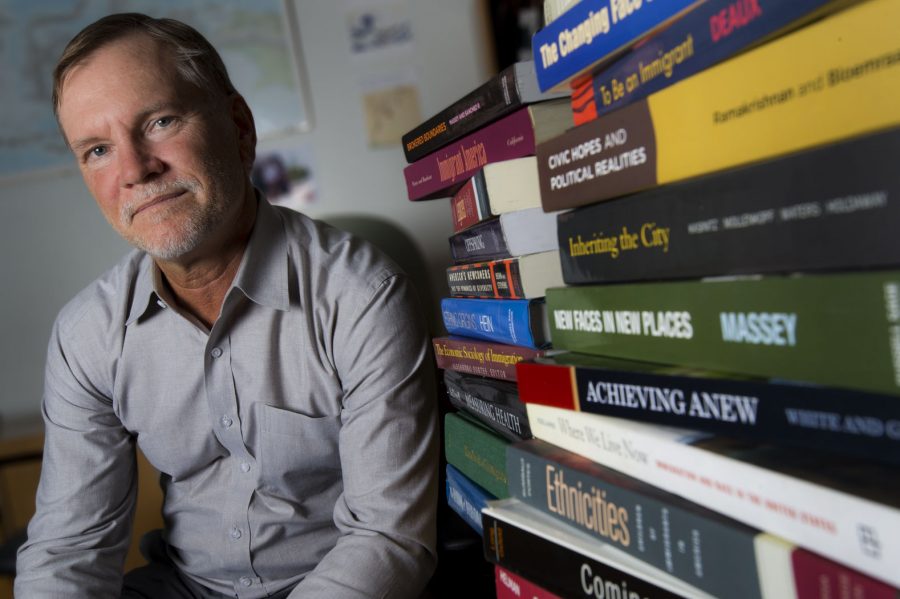

Professor receives millions to study effects of Hurricane Katrina

Mark Van Landingham received millions of dollars to study the long term impact of Hurricane Katrina on different demographics of people in conjunction with other universities including Harvard University.

November 11, 2015

Ten years later, Hurricane Katrina’s effects still linger throughout New Orleans, more in some areas of the city than others. One Tulane professor is exploring these effects.

Mark VanLandingham, a professor of global community health and behavioral sciences, recently received a $6.7 million grant from the National Institutes of Health for a multi-university study of the long-term health, demographic, social and economic effects of Hurricane Katrina.

“We just don’t know how the consequences of disasters play out in the long term, and how these consequences vary for different individuals and different social groups,” VanLandingham said.

Data regarding how and to what extent specific populations affected by the disaster have recovered will be collected over the next two years by researchers from Tulane, New York University, Brown University and the University of Michigan. Tulane, however, is the principal recipient of the award and administers the project.

Studying the long-term effects of a natural disaster like Hurricane Katrina is very rare due to its costs, but also necessary to understand the whole picture.

“The effects of Katrina are likely to vary a lot in the short-, medium- and long-term,” VanLandingham said. “Some people who appeared to bounce back quickly may suffer later from impacts that weren’t adequately dealt with. Others who struggled in the short-term may show resilience in the long run.”

Laura Kelley, a professor in Tulane’s history department and New Orleans resident at the time of Katrina, echoed VanLandingham’s sentiment that those who may have struggled with the immediate threat of Hurricane Katrina some people struggled with is not always indicative of the future.

“What Katrina taught us is that we could have lost New Orleans,” Kelley said. “I hear this story all the time about people who are New Orleanians, who had moved away for a job, and after Hurricane Katrina, quit their job, and moved back to the city, because they were like, ‘Oh, New Orleans will always be there,’ but all of a sudden, Katrina brought home the point that it may not be.”

The mass amount of data and findings that will come out of this project will most likely have significance for future politics. VanLandingham stressed that in order to alleviate the negative consequences of disasters, like Hurricane Katrina, it must be understood that the consequences of the same disaster can vary greatly for different individuals and demographics.

Kelley described what it was like coming back to New Orleans not long after the hurricane.

“We slept outside, and we didn’t hear birds for months and months and months,” Kelley said. “The only noise you heard were the helicopters, you didn’t see rats, you didn’t see anything, it was weird, the lack of life … and then you slowly would see when someone would come back … there were so few people, that you noticed when a neighbor you didn’t know came back.”

VanLandingham hopes to capture the experience of people like Kelley, who came back to and embraced the city of New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, as well as those who were affected more adversely by the disaster and may still be recovering, and everyone in between.

Leave a Comment