Remembering Katrina: Cowen, staff reflect on aftermath of storm

August 26, 2015

This past Saturday, 1,730 new students were welcomed to Tulane University at Convocation. On this momentous occasion ten years ago, however, the ceremony was a little different. Instead of wearing his formal robes, President Emeritus Scott Cowen sported bermuda shorts and a T-shirt.

Instead of rushing students in to their first days as Tulane students, Cowen rushed them out.

“Welcome to Tulane University,” Cowen said. “We were formed in 1834. We’re a fabulous place, we’re delighted to have you here and we’re so delighted to have you here that we have to send you home for four days.”

By Sunday, the entire campus had evacuated except for about 40 faculty and staff that chose to ride out the storm in the Reily Student Recreation Center, as well as about 200 physicians and faculty at the downtown campus hospital.

“I remember it very, very vividly, how horrific it was,” Cowen said about how he and his colleagues stayed in the stairwell away from the windows in case they blew out. “You couldn’t even see outside the Reily Center because the wind and the rain was actually going horizontal, not vertical but horizontal, it was raining so hard.”

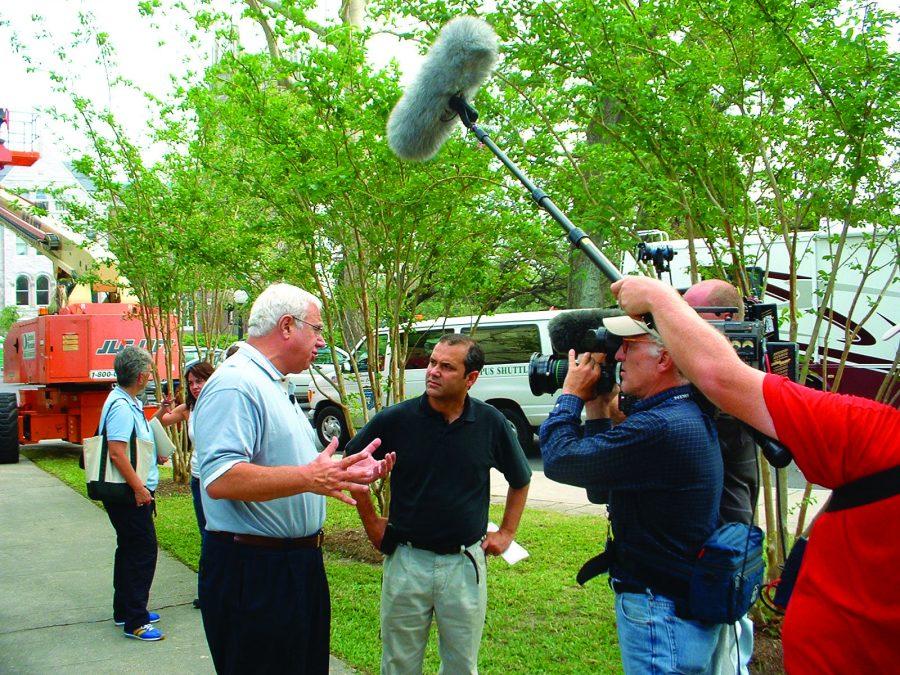

Immediately after the storm, early Monday afternoon, Cowen drove around campus in a golf cart assessing the damage. The initial damage consisted of shattered windows, displaced roof tiles and broken tree limbs.

Later that same day, the levees breached. Cowen and his colleagues spent another night in Reily. The flooding came within 36 hours.

“Where the football stadium is now, there was about three feet of water,” Cowen said. “The water was from back on campus all the way to Freret Street and from Broadway all the way to Calhoun.”

In the 97 degree heat, Cowen and his team lost all power, water and cellphone service.

“That’s when we knew that this was way beyond anything we had ever comprehended,” Cowen said.

In the days after the flooding, Cowen motored around campus in a boat to find food and water. He ultimately broke into Bruff Commons.

“We didn’t have enough provisions to last us but a few days,” Cowen said.

Cowen then received a text from his youngest daughter, his first communication in days. As it was 2005 at the time, the text caught Cowen off-guard.

“I didn’t know what texting was … I had no idea,” Cowen said. “I just saw my phone went off and I was shocked it was my daughter. She became my first lifeline because of texting and that’s how I learned how to text.”

Cowen evacuated the campus after five days.

“It is true I took a boat, it is true I took a golf cart, it is true that we took a dump truck and we ran it through the fence at Audubon Park and we caught a helicopter on the Mississippi River,” Cowen said.

That Friday night, he and his team relocated to Houston to begin recovery plans.

“For all intents and purposes, Tulane University did not exist,” Cowen said.

According to Cowen, three quarters of the Uptown campus was flooded and communication had been lost between the Uptown and downtown staff.

“We made three decisions in that first 24 hours when we were in Houston that really turned out to be important decisions,” Cowen said.

The first decision was to continue paying everyone who worked for Tulane University.

“That was a very big decision because we had no idea where we would get the money to pay everybody but we figured we would because they were going through their own hardships and in fact we did wind up paying people for four or five months at a cost of about 40 million a month,” Cowen said.

The second decision was to reopen Jan. 16, 2006.

“We had to set a goal,” Cowen said. “If we didn’t set a goal, people would think that Tulane would never reopen.”

The third was to ask the heads of higher education to take in not only Tulane students, but all students affected by Katrina during the fall of 2005 so that their education would go uninterrupted.

“That started the process after Katrina of rebuilding the university and rebuilding New Orleans, a process that took us about two or three years before we were relatively secure … Now we’ve been at it 10 years and we still have issues related to Katrina,” Cowen said.

The predicted return rate was only 50 percent, but nearly 86 percent of students decided to return to Tulane after Hurricane Katrina.

“I think we have terrific students that come to Tulane,” Cowen said. “They were watching what was going on around the country and they wanted to come back to help the university and to help the city.”

Enrollment in the fall of 2006, however, was impacted by Hurricane Katrina. Only 823 new students enrolled. At the time, a typical freshman class consisted of about 1,600 students.

After Hurricane Katrina, public service was incorporated into the core curriculum, creating a new angle for recruiting students.

“Our pitch was if you really want to make a difference in your life there’s no better place in the world than to come to Tulane and New Orleans at this moment in time,” Cowen said. “So you continue to get a first rate education in the classroom as you always would, but you’ll get an unprecedented opportunity to participate in the recovery of New Orleans.”

The university’s recovery has “far exceeded my expectations, it’s way beyond anything I ever thought,” Cowen said.

Tulane commits to public service

The post-Katrina recovery efforts drew in not only new service-oriented students, but faculty as well. Bridget Smith, the Center for Public Service program manager, came to New Orleans in March 2006 after volunteering abroad.

“It just seemed like the right thing to do,” Smith said. “I wanted to give back to my nation.”

Smith worked in the Red Cross Hurricane Recovery Program and assisted families living in Federal Emergency Management Agency trailer parks covering 13 parishes. Some of these parks were in wooded, rural areas that did not get cellphone service.

“[The] families that had been living in the Ninth Ward … had a super cohesive social network and community,” Smith said. “Everybody relied on everybody and now they were living completely disconnected from the rest of the world.”

Smith’s job was to connect families to resources after the hurricane. Many displaced hurricane victims, however, were not only disconnected from resources, but loved ones as well.

“FEMA tried to keep some families together, but those trailers were so small, some families were too big for one trailer,” Smith said.

Her colleague Benjamin Brubaker, Center for Public Service senior program coordinator, was entering his sophomore year at Tulane when Hurricane Katrina hit. Brubaker housed 15 Tulane students and two Loyola students at his home in Shreveport, Louisiana when the school was evacuated.

In the past when hurricanes warnings came and went, campus closings due to an impending storm were like a “Hurrication,” Brubaker said. “A couple days off school.”

According to Brubaker, there had been similar storm predictions the year before Katrina that had not come true.

Therefore, students were not expecting Hurricane Katrina to be any more dangerous than storms of the past.

“We didn’t really know until we saw the damages,” Brubaker said.

Katie Houck, Center for Public Service assistant director, joined the Tulane community as the Newcomb College assistant director for student programs. She was at Tulane for only three months before Katrina hit, and spent the next 18 months doing recovery work.

“Overall the university is in a better place now than it was,” Houck said. “Obviously it had to make some really hard decisions that were unpopular, but I think the university itself is in a stronger place now because of those decisions.”

One of those decisions was to officially incorporate public service into Tulane’s core curriculum.

“I think most people can see this has put us on a different path and has benefits, benefits for the community and benefits for the university itself,” Houck said.

Tulane’s new emphasis on public service has drawn in a student body more passionate about the issues in their community and contributing to these issue’s solutions.

“I think there were already a lot of students at Tulane who didn’t know they cared about service until they experienced Katrina, and I think every year since then has attracted largely a different type of student who comes here for that experience,” Brubaker said.

Lawrence Smith III, the Center for Public Service departmental administrator, is a New Orleans native. The city’s opinion of Tulane and its relationship with the Tulane community changed for the better after Katrina, according to Smith.

“After Katrina the students and faculty went out into the community and rubbed elbows and stuck, not just touched them, but actually bonded,” Smith said.

His colleagues agreed.

“Before Katrina, Tulane very much had the reputation in the city that Tulane will come into the community and use their resources and take that back to the university and do their research and get recognition, but then that never trickles back down to the community,” Houck said. “I think after Katrina that relationship has very much changed. The community is benefitting from our resources more and more.”

Leave a Comment