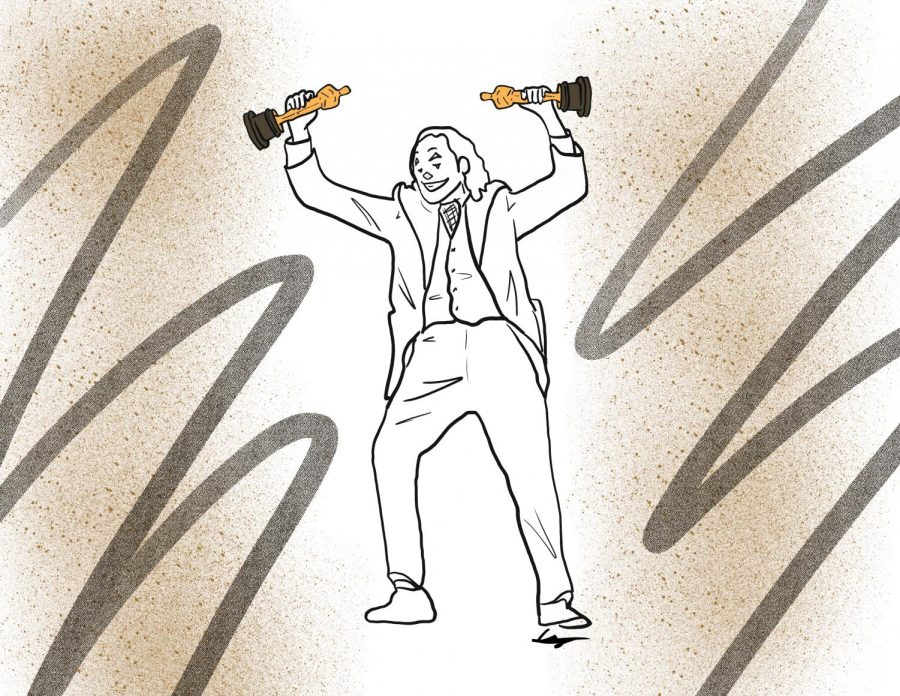

Joker deserves Oscar nominations despite blowback

Czars Trinidad | Senior Staff Artist

Joker has won 11 Oscar nominations

January 23, 2020

Love it or hate it, there’s no denying “Joker” is a cultural phenomenon. After winning Best Picture at the Venice Film Festival in September, the Todd Phillips-directed Joker origin story became perhaps the most anticipated film of 2019. When it finally hit the box office in October, it became the first R-rated film to gross over $1 billion.

Reviews of the film were polarized and became even more so after “Joker” received 11 Oscar nominations, more than any other film. Though there are plenty of good faith critiques of the film as a work of art, some critiques from film critics, journalists and social media users dismiss the film for the wrong reasons. “Joker,” a superhero film that examines society’s mistreatment of the mentally ill, has become an unlikely victim of outrage culture.

The main political critiques of the film include the film being “problematic” because it supposedly promotes gun violence, glorifies white male loners and, especially in light of its Oscar nominations, takes attention away from issues facing women and minorities. The outrage surrounding these overstated claims shows how political disputes have spilled over into the entertainment industry and contributed to a polarized climate.

There is some legitimacy to the concern that the film could spark violence by portraying a character who finds his voice through violence. There is, however, no evidence of “Joker” leading to gun violence, despite the hype and hysteria surrounding the film.

Additionally, the point of the film is not to glorify violence, but to condemn it. As director Todd Philips himself states, the film was meant to spark a conversation around gun violence. As its R rating suggests, the film portrays violence, but this doesn’t in itself make “Joker” any more “problematic” than “John Wick” or “Pulp Fiction.”

Other claims surrounding the film have less legitimacy. A journalist for Vanity Fair, for example, claims “Joker” is one of several films nominated for Best Picture about “white men who feel culturally imperiled.” Another article on another entertainment site claims that Arthur Fleck, the character who becomes the Joker, is “based upon the archetypes of white supremacists and ‘incel’ culture.”

A person of any race can be a lonely, mentally ill clown who snaps and becomes a violent criminal. Race is not a major theme in “Joker.” And that’s okay. A film doesn’t have to center race, gender or sexual identity to have artistic value.

This point brings us to the final critique: that films made by women and people of color deserved some of the nominations “Joker” ate up, as some articles suggest. Accusing the Academy of sexism accomplishes little.

Academy members are free to choose which films they believe are best, and claiming racism or sexism to delegitimize their picks takes away from identifying the true issue at hand. The real, underlying issue deserving of our attention is the relative lack of female directors and directors of color in Hollywood being given opportunities to make well-funded, well-marketed and high-grossing films.

Director Todd Philips shares some of these concerns. In an interview with The Wrap, he claimed that though his film was not meant to “push buttons,” some people seemed eager to pounce on a film they perceived as problematic.

“I think it’s because outrage is a commodity, I think it’s something that has been a commodity for a while,” Phillips said in the interview. “What’s outstanding to me in this discourse in this movie is how easily the far left can sound like the far right when it suits their agenda. It’s really been eye-opening for me.”

Though Philips specifically blames the far left, the impulse to react with outrage transcends right and left, extending to anyone along the political spectrum who seeks to politicize or weaponize media. Of course, people are free to like or dislike a film for any reason that sticks out to them, but arguing a film is morally or artistically bad solely because it doesn’t confirm your existing political beliefs doesn’t make for productive discourse.

As college students, we should be careful how our political biases affect our analyses of media. Movies are movies, not opportunities to show off all your correct political opinions. Rather than rushing to dismiss certain films, ideas or people on grounds of racism or sexism, let’s instead engage in thoughtful analysis and debate.

Leave a Comment