No headline provided

October 21, 2011

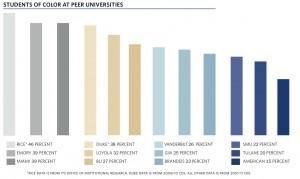

The racial and ethnic diversity of Tulane’s total undergraduate population is lower than that of peer institutions.

According to 2010-11 numbers from the Common Data Set, a set of standardized higher education statistics, “students of color” compose 20 percent of Tulane’s undergraduate population. Meanwhile, Emory University’s and University of Miami’s student population both have 39 percent, Vanderbilt University’s has 26 percent and Rice University’s has 46 percent students of color. Students of color include students who identify as black, Hispanic, Asian, American Indian/Alaskan Native, Pacific Islander or multiracial.

Tulane’s black undergraduate population, at 8 percent, is comparable to that of its peer institutions. Much of the difference in ethnic representation between Tulane and the other schools lies in its Hispanic and Asian populations. Five percent of Tulane’s undergraduates are Hispanic and 5 percent are Asian. Meanwhile, the Hispanic undergraduate percentage is 25 percent at Miami, 10 percent at Southern Methodist University and 12 percent at Loyola University New Orleans. The undergraduate populations at Duke, Emory and Rice are all more than 20 percent Asian. Dean of Admissions Earl Retif

said that a variety of reasons could explain Tulane’s smaller Asian population.

“You’d have to take a look at all kinds of factors that go into why a particular school is more desirable than another school,” Retif

said. “But distance is one, particularly for ethnic students, more so than Caucasian students.”

School of Continuing Studies’ Impact on Diversity

Tulane’s undergraduate student population is split between the five schools of Newcomb-Tulane

College and the School of Continuing Studies. While Tulane’s black undergraduate population is similar to that of its peer institutions, according to the Tulane Registrar 70 percent of the black undergraduate population in 2010-11 was in the School of Continuing Studies. Without the School of Continuing Studies, Tulane’s undergraduate student population is 3.55 percent black.

School of Continuing Studies students can take classes at Newcomb-Tulane

College, and other undergraduates can do the same in the School of Continuing Studies. However, all School of Continuing Studies students are part-time, only 2 percent live on campus and some take classes on the Biloxi and Madison, Miss. campuses. In fact, undergraduate School of Continuing Studies students are represented in the Graduate and Professional Student Association, not the Undergraduate Student Government.

While the other universities have part-time undergraduate students, 23 percent of Tulane’s undergraduate population attends part-time. Of Tulane’s peer institutions, Miami is the closest to Tulane’s percentage with eight percent part-time students.

Richard Marksbury

, dean of the School of Continuing Studies, said that a major intention of the school is to recruit students from New Orleans who can only attend college part-time because of work and family responsibilities. At the School of Continuing Studies, where the average student is 28 years old, any person with a high school diploma or GED can attend.

“Our philosophy is we let people come here and prove themselves once they’re here,” Marksbury

said. “Once you walk into the door and enroll here, the standards that we apply to our students are the same as the rest of the university.”

Seventy percent of undergraduate Continuing Studies students come from the New Orleans Metropolitan Area, and the New Orleans population itself is 62 percent black. Marksbury

said it makes sense that the percentage of black students at the School of Continuing Studies would be greater than at Newcomb-Tulane

College because the latter draws from across the country, and 12.6 percent of the national population is black.

Retif

said that the School of Continuing Studies does not follow the same admissions guidelines as Newcomb-Tulane

College, and that might be why there are more minority students there.

“The School of Continuing Studies, with lower tuition rates, class times designed for working students and an open admission policy that requires a high school diploma or GED, may offer greater access to some minority or first-generation college students,” Retif

said.

DIVERSITY AND ADMISSIONS

Students have noticed the discrepancies between racial groups on campus. Many believe that the root of the diversity issue is the admissions process.

“Due to many factors, including demographics, family income, cultural preferences and the academic achievement gap between minority and white students, more than 60 percent of students taking College Board exams [such as the SAT] for universities nationwide, including Tulane, are white,” Retif

said.

Tulane currently has several initiatives in place to attract minority students, including a partnership with the Posse Foundation, a national organization that recruits urban public high school students from certain areas and sends them to universities in groups, or “posses.” The Newcomb-Tulane College Summer Transition Program allows minority students from the New Orleans area to spend a summer taking courses at Tulane. If the students do well, they are eligible for admission to the university.

“It’s not like the university is not doing anything [to recruit minority students],” Assistant Vice President for Intercultural Life Carolyn Barber-Pierre said. “They have been working with a number of initiatives to work with a number of underrepresented groups.”

Jeff Schiffman, senior associate director of the Office of Admissions, said that Tulane has programs to increase the percentage of students of color.

“Between the fly-in [of admitted students of color], between the Posse foundation, between our partnership with the Kipp program, between the high schools that we visit…as far as what we’re doing, we know there’s always improvements that can be made, but we’re really doing a lot to try to recruit students of color,” Schiffman said. “It’s just one of those things where you can only do so much.”

He said, however, that race and ethnicity are only parts of diversity. When making acceptance decisions, he said, admissions looks for diversity in a variety of areas, from geographical origin to unique talents.

“Whether it be diversity based on a student being First Generation College, a student being a fencer … those are all things that come into play in the admissions factor, but we don’t admit them based on those factors,” Schiffman said. “We admit them first and foremost based on their academic performance, their SAT scores and their extracurricular activities.”

Despite Tulane’s recruitment efforts, some students said they are displeased with how the university recruits students of racial minorities.

“One way [to attract minority students] is to stop using current programs and measures as copouts,” said Matthew Bourda, president of the Black Student Union. “A prime example is the Posse program. It does attract students of color, but it is primarily a leadership initiative. I think Tulane has gotten a little too safe with it, as a means of attracting students of color.”

Barber-Pierre said the Posse program brings in 10 to 15 students each year from the Los Angeles area. For the class of 2015, it brought in 10 students. For the next year’s incoming freshman class, there will also be a “posse” from New Orleans. Similarly, of the approximately 20 students who participate each summer in the Newcomb-Tulane College Transition Program, Barber-Pierre estimates that four to seven enroll each year.

Because Tulane’s most advertised diversity recruitment programs do not enroll a large number of students, some students feel that the university is not making enough of an effort to attract minority students.

Efren Lopez, president of the campus Latino organization Generating Excellence Now and Tomorrow in Education, or GENTE, said he does not feel that Tulane is concerned with recruiting minority students for the sake of improving diversity. Lopez said that from speaking with administrators such as President Cowen, he feels that getting students of color is on Tulane’s agenda mainly to increase rankings.

“It’s always, ‘Our retention rates are such and such,’ and then rankings come into the conversation, and then diversity comes into the conversation,” Lopez said. “It’s interesting that it’s always in that order.”

Barber-Pierre said that a major obstacle in bringing racially and ethnically diverse students to campus is the high price of Tulane’s tuition.

“It’s difficult to recruit students of color to a predominantly white campus, particularly with the price tag that we have and with the requirements to get in,” Barber-Pierre said. “The best and the brightest ethnic students are being wooed all over the country by major institutions that have more money. It’s going to be difficult to compete with some of the other incentives which other schools can give.”

Nonetheless, students said they feel that Tulane can do more to attract more students of ethnic minorities.

“You cannot possibly tell me that there are not more qualified black students who can come to this school,” Thorne said.

PERCEPTIONS OF DIVERSITY ON CAMPUS

The Office of Multicultural Affairs’ April 2010 Diversity Climate Survey assessed the opinions of 3,840 undergraduate and graduate students to learn their perspectives about racial diversity at Tulane.

Of the students who completed the Diversity Climate Survey, 59.14 percent of students identified as White/Caucasian, 17.55 percent identified as Asian/Pacific Islander, 12.66 percent identified as Black/African American, 8.35 percent identified as Hispanic/Latino and 1.73 identified as Native-American or Alaska native or indigenous.

Beyond ascertaining the number of minority students on campus, the Diversity Climate Survey report listed significant findings and responses from the surveyed students. The report states: “African-American students disagreed strongly with the statement, ‘I feel welcome on campus as a member of a racial/ethnic minority group,”‘ and “African-American students and Native-American males strongly agreed that they don’t belong at Tulane.” Additionally, it found that “African-American students were the only group to agree with the statement that “Tulane University does not promote respect for racial/ethnic diversity'” and that “African American and Hispanic females and international students strongly disagreed with the statement ‘I know where to find information related to discrimination and harassment policies and reporting procedures at Tulane University.'”

“When students who come to campus see that there isn’t any diversity, they find themselves lost,” Lopez said. “Some students find it hard to reach out to OMA, and those students who don’t reach out get lost and drop out of school.”

When the Diversity Climate Assessment asked, “would you recommend Tulane to a friend or relative?” one responder said:

“I love Tulane, but for my friends and family, as an African-American, I would not tell them to come here. To me, I think that Tulane makes a huge effort but it falls short. They’re unable to recruit students from different races because the moment you step on campus its a white-out.”

Barber-Pierre said that a main problem on campus is that students of color do not feel that they have a community or a forum through which they can communicate.

“For students of color at a predominantly white institution, they need to have some identifiable community that they feel they can interact [with],” Barber-Pierre said.

Some students, however, said they feel that the issues of diversity on campus are more rooted in the divide between students of color and white students. Derek Landrum, a Students Organizing Against Racism student of color co-convener and sophomore at the School of Continuing Studies, feels that animosity stems from the fact that few minority students are active on campus.

“Diversity is having multiracial people in a space,” Landrum said. “Tulane is very good at that. But are students of color actively being a part of this campus? No. If the Office of Multicultural Affairs is the only office addressing these issues, that’s an issue.”

Ethnic minority students on campus also feel that there is a divide between athletes and non-athletes.

“I feel like I got here on my own accord,” Bourda said. “I don’t think I’m an affirmative action kid. But I feel like I’m a little bit overshadowed by the athletes because people give them so much praise and attention. Meanwhile, students who are not here for athletics do just as much work.”

According to Barber-Pierre, 95 out of 209 black students were athletes in the 2010-11 academic year. In this year’s freshman class, 15 out of 48-53 black students – numbers differ between OMA and the Office of the Registrar – are athletes.

Though students said they recognize the divide, they do not necessarily begrudge the athletes for not intertwining with the rest of the multicultural community.

“I wouldn’t blame the athletes,” Thorne said. “They have to become an isolated group because it helps them become a better team, and they just don’t have time to get involved in the other organizations. For other students of color, that’s all they have. For the athletes, the athletics program is taking care of the students of color who are athletes. You don’t see a lot of scholarship athletes in student organizations.”

Athletes recognize that they have access to a larger than average number of minority students simply by being a part of the athletics program.

“[Because I’m a football player,] I’m always around people of color,” junior Chris Hanuscin said. “People who aren’t athletes don’t get that brotherhood. I feel better. I feel more at home.”

Leave a Comment