Your donation will support the student journalists of Tulane University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

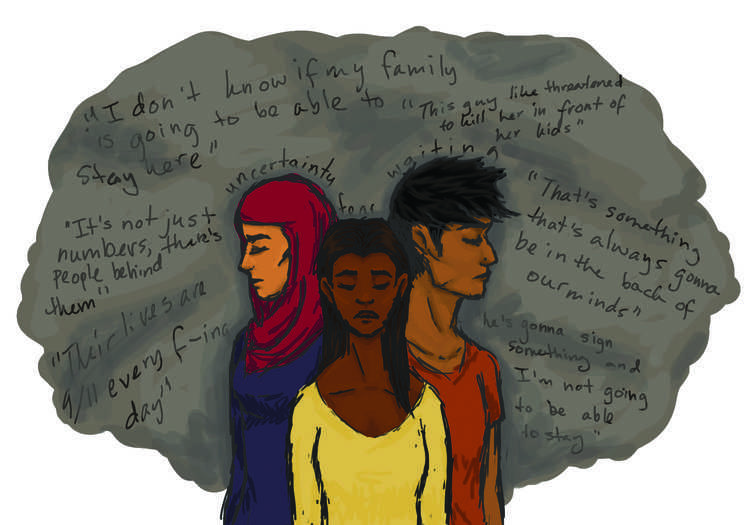

Illustration by Adelaide Basco

‘Muslim Ban’ intensifies Tulane students’ fears and uncertainty

February 2, 2017

Tulane sophomore Haneen Islam said she is wrought with uncertainty, waiting for news of whether or not her sisters will be allowed to remain in the country after President Donald Trump’s “Muslim Ban.” While Islam is U.S.-born, her sisters are both from Pakistan, complicating their immigration status.

The “Muslim Ban“ is an executive order signed by Trump on Friday that temporarily bans citizens from Iraq, Iran, Libya, Somalia, Sudan and Yemen while permanently banning Syrian refugees. Like Islam, many Tulane students find themselves affected by the changing immigration policies, whether it be through their own immigration status or through the effects on their families.

A sense of insecurity looms over the affected community, whether or not one’s country is included in the executive order, as it waits for more information from the Trump administration and from Tulane itself.

Islam finds herself in an odd position. While she was born in the United States, her parents and two older sisters were born in Pakistan. Her parents visited earlier in the year and returned to Pakistan, but her sisters remain in the United States awaiting the result of their pending visa extensions, which could be threatened by the new immigration policies.

“The strongest emotion I’m feeling right now is uncertainty because I don’t know what’s going to happen at this point,” Islam said. “I don’t know whether [my] family is going to be able to stay here. I don’t know whether they’re going to be able to come and go as they please. I don’t know whether having Pakistan stamped on my passport is gonna affect me in any way.”

Sophomore Sarah Amkieh has family in Syria and said she believes the Tulane community needs to be more accepting of Muslim people.

Sophomore Sarah Amkieh, who is Syrian-American and Muslim, said she is worried about Islamophobia increasing on campus in light of the executive order. She is more worried, however, about her friends who live in the greater New Orleans area, especially for Muslim women who wear the hijab. Her friend, who wears the hijab and is a Tulane student, said she received threats following the election.

“She was in the park one time and this guy threatened to kill her in front of her kids,” Amkieh said. “He had a big dog and he was like ‘we can’t kill em yet’ to the dog.”

This type of Islamophobia and prejudice is oftentimes attributed to the fear and blame placed on Muslims in the media for terrorism both in the United States and abroad. Amkieh said she feels people, especially those in the Tulane community, should think more critically about why people are in many instances forced to come to United States.

“Muslims that are fleeing Syria and other countries in the Middle East are the ones who have suffered most from terrorism, not white people in America,” Amkieh said. “You know, like 9/11, how everyone is so somber, their lives are 9/11 every f—— day. These people are fleeing what we’re scared of too. We’re scared of ISIS? They’re scared because 98 percent of the people they kill are Muslim.”

This sense of uncertainty is not limited to international students from the banned countries. For many, the executive order symbolizes just the beginning of Trump’s long promised and vast immigration policy changes.

Sophomore Patrizia Santos is awaiting the results of her pending Green Card and said she feels unsure about the future. Photo by Sam Sitt

For Venezuelan sophomore Patrizia Santos, the status of her pending green card hangs in the balance.

“I’m in the process of changing my immigration status, so that was a very big threat,” Santos said. “[Trump] said he was going to eliminate the J-1 visa, and a lot of my friends are international students. So they were planning on trying to get that visa once their visa here expired to extend their time here studying, but if he was gonna do that, suddenly it wasn’t an option anymore.”

Tulane President Michael Fitts and the Office of International Students and Scholars both sent out emails reaching out to international students who could be affected by the new policies. Santos said though she appreciated the email, in some ways it worsened her anxiety and confusion about what the university would do to protect its international students.

“That’s something that’s always going to be in the back of our minds,” Santos said. “Like when we do school work, when we do anything, we’re always going to be thinking like ‘oh, is he gonna sign something that I’m not going to able to stay.’”

Santos said she just wants people to see the humanity behind the immigration statistics.

“It’s not just numbers: there [are] people behind,” Santos said.