Your donation will support the student journalists of Tulane University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Living in a sinking city

Moving to high ground

February 9, 2017

From population and sea levels to global instability and nuclear warfare, facets of our world are growing. Many cities, however, are focused on what is vanishing — their coasts. This ticking clock could be just as fatal as the drop of a bomb. Our danger is water.

The New Orleans and Tulane communities might be looking for a new home, as Louisiana loses land at the rate of a football field every 45 minutes. The 2017 Master Plan states that more than 1,800 square miles of coast have been lost in the past 80 years due to both natural and man-made causes “including climate change, sea-level rise, subsidence, hurricanes, storm surges, flooding, disconnecting the Mississippi River from coastal marshes, and human impacts.”

Louisiana’s Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority released the Coastal Master Plan in 2007 as a guide for mitigating coastal land loss, as scientists have no way of halting the loss of Louisiana’s coastline. It aims to revise the plan every 5 years.

The 2017 Master Plan is the third edition and is open to public comment until March 26. The finalized plan will then be introduced in the Louisiana state legislature in the 2017 legislative session. The new plan focuses on many projects that will rebuild wetlands and land, replace sediment, update levee systems across the state and focus on elevating the threatened communities.

“I think the message [of the 2017 Master Plan] … is significantly more severe than any of us thought even five or 10 years ago,” King Milling, chairman of the Governor’s Advisory Commission on Coastal Protection, Restoration and Conservation, said in an interview with The Times-Picayune in October.

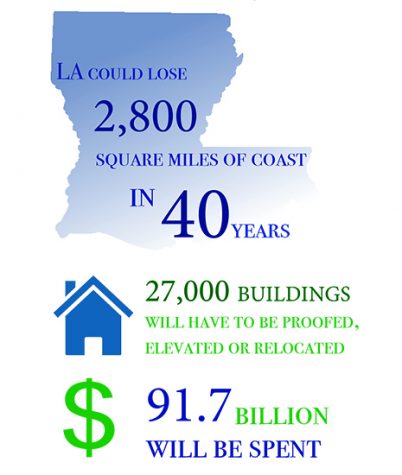

Even if the plan is executed, Louisiana still stands to lose 28,000 square miles of coast within the next 40 years, and the 27,000 buildings on that land will have to be flood-proofed, elevated or relocated. The alternative is the loss of Louisiana’s “boot,” the bottom third of the state.

Cam Lutz | Staff Artist

There are, however, many people working to turn back the clock and keep Louisiana on the map.

Robert Moreau, an adjunct professor in the Tulane A.B. Freeman School of Business, is one of those people. Moreau spends his days working at the Turtle Cove Environmental Research Station, which focuses on wetland education and research. He uses his nights to teach about sustainability and its relationship to the economy, including how Louisiana’s coast affects local businesses.

“We’ll never reclaim all of our lost wetlands, nor will we stop coastal wetland loss or sea level rise, but we can do things that can help us live more sustainably along the coast for a longer time — more so than if we do nothing,” Moreau said.

For Brian O’Malley, assistant vice president of capital projects federal and grant funded services, every second counts. He is always on the move between campuses and projects, from Howard-Tilton Memorial Library to the closing Mississippi Coast campus.

O’Malley works mainly on retrofitting existing buildings with money granted to Tulane by the Federal Emergency Management Agency following Hurricane Katrina. He works specifically on mitigation efforts, which are ways to reduce risk and possible damage, such as elevating buildings to prevent flooding. O’Malley said elevation in design and sustainability is a top priority when developing a new building or updating old ones.

“Twenty or 30 years ago, when we designed a building we looked at putting the mechanical and electrical in the basement like we did [in Howard-Tilton] — not a terribly good idea,” O’Malley said.

O’Malley said that Tulane is looking towards the future, but there are not current plans to retrofit or elevate on a campus-wide level, aside from buildings affected by Hurricane Katrina, including Howard-Tilton and McAlister Auditorium. Tulane has limited space to relocate students, classrooms and offices for such a large-scale process.

Mark Davis, director and senior research fellow of the Tulane Institute on Water Resources and Law Policy, comes into the office every day to chat with his co-workers “about what’s in the news,” noting that “there’s always something in the news about water — what’s exciting.”

Davis spent a lot of time looking into how Louisiana can pay for the amended Master Plan. The Master Plan’s cost jump from $50 billion to $92 billion is significant, especially when the state is facing at least a $600 million budget shortfall, according to Governor Jon Bel Edwards in December. Edwards announced plans on Jan. 23 to sue oil and gas companies and cover some of the Master Plan’s cost.

Davis said some are hoping that federal money or the $20.8 billion Deepwater Horizon oil spill settlement will fund the plan, but Davis believes the funding will not come from a single source. The Water Institute released a paper, co-written by Davis, called “Financing the Future,” which outlined possible funding options after the plan’s current allocation runs out.

Finding the needed funding in a short amount of time is a larger problem. Louisiana lost more than 200,000 square miles of land in the three weeks following Hurricanes Katrina and Rita in 2005. Davis said he believes that if another active storm season occurred, the 40-year prediction could be too optimistic for some communities.

“Time is the resource we have the least of … You don’t have 40 years. Maybe if you’re lucky, you do, but you better start soon,” Davis said.

Community members like Moreau, Davis and O’Malley are not working alone to combat the land loss but alongside a community that reaches from local to state and federal levels. Groups working toward this goal in the Tulane community include Tulane Green Club, Divest Tulane, the Office of Sustainability and Facilities Services, the Center for Public Service and its community partners including The Green Project, Alliance for Affordable Energy, Bayou Land Resource Conservation and Development Council and Lake Pontchartrain Basin Foundation.

With so much at stake, Davis said there are many decisions left to be made, especially with limited resources and a countdown that’s already nearing midnight.

“Somebody once told me when you’re looking at a problem and it looks like nobody’s doing anything to really make things better, you ask, ‘Well, whose job is it to do something here?’ Well, it just might be yours.”

Chris McLindon • Feb 9, 2017 at 12:16 pm

In the era of fake news and alternative facts we must hold academic institutions to a higher standard for accuracy and fact-checking in stories like this. The contention that “Louisiana loses land at the rate of a football field every 45 minutes” is not supported by science. The fact that the statement in this article is hyperlinked to another piece of journalism, and neither includes a reference to a peer-reviewed scientific publication is deeply concerning. This practice heightens the problem with journalistic accuracy by creating an echo chamber of unsubstantiated claims.

WWNO reporter Jesse Hardman explained the origin of the claim that Louisiana “is losing a football field an hour” in his March 3, 2015 story titled “Why Do We Measure Wetlands Loss In Football Fields”. The original claim came from a Super Bowl commercial, and it should be referenced as such. This claim is by far the most commonly used description of the status of the coastal wetlands in the popular press.

It is completely inaccurate, and its pervasive use underscores a significant problem with the press and science literacy. The metaphor is a corruption of a statement that originated with the U.S.G.S. Scientific Investigations Map 3164 “Land Area Change in Coastal Louisiana from 1932 to 2010”. The pamphlet that accompanies the map includes the sentences “Trend analyses from 1985 to 2010 show a wetland loss rate of 16.57 square miles per year. If this loss were to occur at a constant rate, it would equate to Louisiana losing an area the size of one football field per hour.” The analysis done by the U.S.G.S. was a very accurate trend analysis of rates and patterns in changes in land area over a fixed period of time. The football-field-an-hour metaphor was used to provide a visualization for the reader. It was clearly intended to represent an average rate of land loss determined by trend analysis over a quarter of a century time span. It was not intended to represent a constant rate of present-day land loss, as it was used in the article. The U.S.G.S. document clearly states that land loss rates have been decreasing from the high rates observed in the 1970s. It also noted “an interesting finding of this analysis may be observed in the increase in net land area in the 2009 and 2010 datasets.” These are the last two years of the study. The data indicate that not only is the application of the football metaphor for present-day land loss incorrect, the actual present day figures for land area change are closer to net gain than they are to net loss.

Tulane would do the residents of south Louisiana a favor by taking the lead on correcting this commonly quoted alternative fact.