Your donation will support the student journalists of Tulane University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Courtesy of the Georgetown Memory Project

Cornelius Hawkins’ gravesite is pictured at the Immaculate Heart of Mary Cemetery in Maringouin, LA. Hawkins was born in 1825, was sold in 1838 and died in 1902.

“What happened to the people”: 1838 sale of 272 people challenges universities to evaluate ties to enslavement

October 19, 2017

“For the promotion and the encouragement of intellectual, moral and industrial education among the white young persons in the city of New Orleans.”

These are words of the original charter, penned by Paul Tulane, Louisiana Congressman Randall Lee Gibson and others, that served as the foundation for Tulane University.

More than 1,000 miles away, the Maryland Jesuits, an order of Roman Catholic men, operated Georgetown University. Four years after Tulane opened its doors as the Medical College of Louisiana, the Jesuits, on behalf of Georgetown, sold 272 enslaved people to three sugar plantations in Southern Louisiana. The sale saved Georgetown from bankruptcy.

“It was incredibly sad to find out the actual story behind my ancestors and that they were in fact slaves at an institution and were sold and forced to travel halfway across the country to another slave owner,” Elizabeth Thomas, incoming Georgetown graduate student and a descendant of one of the 272, said.

Thomas, a New Orleans native, is attending Georgetown this spring to earn a Master’s degree in journalism. Georgetown accepted her with legacy status, something the university has offered to descendants of the 272 sold who wish to pursue an education at Georgetown.

Attending Georgetown as part of the legacy initiative are fellow descendants, Thomas’ brother Shephard and Mélisande Short-Colomb. Short-Colomb, who, in her words, “grew up in the shadows of Tulane University” in Uptown New Orleans, is Georgetown’s oldest degree-seeking undergraduate at 63 years-old.

The decision to give descendants legacy status in admissions came after a series of student protests at the university in 2015 after Georgetown’s historic ties to enslavement and the sale caught the attention of student activists.

“If the students hadn’t done their protesting, this would not be happening right now …” Karran Harper Royal, a descendant and one of the co-founders of the GU272 Descendants Association, said. “It was only because back in 2015 when students across the country were protesting injustice on their campus that the students in Georgetown were sitting in their president’s office.”

Following the protests, university officials considered potential courses of action to address the history, including renaming buildings, changing the campus tour script to acknowledge the university’s ties to slavery and putting up plaques. Richard Cellini, a Georgetown College and Georgetown Law School alumnus, found these proposals lacking.

Cellini’s question: “what happened to the people?”

“Even the Titanic had survivors”

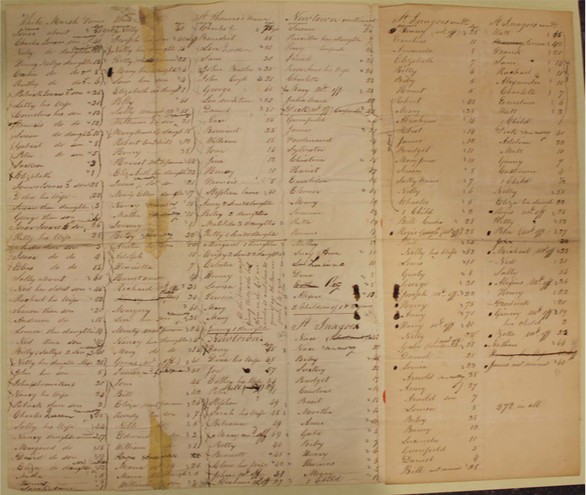

Courtesy of the Georgetown Memory Project

The pre-sale census pictured was drawn up in 1838 in Maryland and used as the basis for the sale of 272 people. It was signed on June 19, 1838.

According to Cellini, a senior member appointed by Georgetown’s president to a working group tasked with brainstorming potential university-wide responses to the school’s ties to the slave trade told Cellini all 272 of the enslaved people sold in 1838 had died of a fever soon after they arrived in Louisiana, leaving no trace and no descendants.

“[This] struck me as preposterous. I mean, you know even the Titanic had survivors …” Cellini said.

Frustrated and with a Google search bar as his only initial tool, Cellini began to search for some of the 272 and their descendants on his own. Within 15 minutes, he found two of the enslaved people sold by Georgetown and one descendant. Within days, his informal pursuit of answers became the Georgetown Memory Project.

Independent from the university, GMP has found 212 of the 272 enslaved people so far and more than 5,000 descendants, many of whom still live in Southern Louisiana. As far as Cellini knows, it is the only systematic effort underway to identify and locate the enslaved people and their descendants.

“We find no direct evidence of that”

Courtesy of the Georgetown Memory Project

“West Oaks was one of three large sugar plantations in southern Louisiana to which the GU272 were sold in 1838. The land is still used for sugar cane production today.

Georgetown is neither the first nor the only university dealing with its historical connections to slavery. Columbia, Rutgers, Yale, Washington and Lee and others have begun initiatives and projects in recent years to acknowledge institutional ties to enslavement.

Tulane, however, has held fast to the university’s lack of connection to the slave trade or enslavement.

“Our archivist, Ann Case, tells me that Tulane University never owned or sold enslaved people, nor does there appear to be any direct evidence that enslaved labor was used in the construction of our campus buildings,” President Michael Fitts said. “Tulane’s original campus downtown, before we moved to our current location uptown, was built before the Civil War. It might be possible that the construction company hired by Tulane to build those original buildings could have used enslaved labor, but we find no direct evidence of that.”

According to Case, Paul Tulane likely earned all of his money through his mercantile business and did not use slaves in his home or business. She added that while there has been speculation about Paul Tulane’s father, Louis Tulane, having owned slaves in Haiti, it is currently unknown whether or not he participated in the slave trade. Paul Tulane’s brother, also named Louis Tulane, did own and ship several enslaved people in the 1820s.

Before becoming president of Tulane’s first board of administrators, Rep. Randall Lee Gibson was a prominent Confederate general whose family owned enslaved people. It has been speculated, though not confirmed, that he owned about 40 enslaved people and that his father Tobias Gibson owned several sugar plantations in Louisiana, all kept afloat by the labor of more than 200 enslaved people.

Case said that to her knowledge, “Tulane University does not have any ties to the slave trade in the direct manner that Georgetown does, or in any manner beyond existing in a slave economy during the years 1834-65.”

Laura Rosanne Adderley, associate professor of African Diaspora History, head of Africana Studies at Tulane and a specialist in the Atlantic slave trade and black enslavement, said slavery was an ingrained economic institution in the United States before emancipation. In her estimation, there are virtually no institutions founded before 1865 that shoulder no blame.

“If you see something, not just in the South, but if you see something was built a long time ago in this country — the odds on enslaved hands having their hands on it are high,” Adderley said.

“Everyone knows that slavery existed. Everyone knows that the South’s economic and political systems were centered around the slave trade …” Anfernee ‘Bubba’ Murray, a junior and programs and events chair for Students Organizing Against Racism, said. “This history is my history as a Black NOLA native as well as Tulane’s history, and it deserves to be heard.”

Short-Colomb urged people not to limit their understandings of enslavement and its aftermath as an exclusively Southern problem.

“People like to think these issues are exclusive to the South,” Short-Colomb said. “They aren’t. Racism, disenfranchisement and laws of disenfranchisement are across America. It’s not just the South.”

“Exactly where we left them”

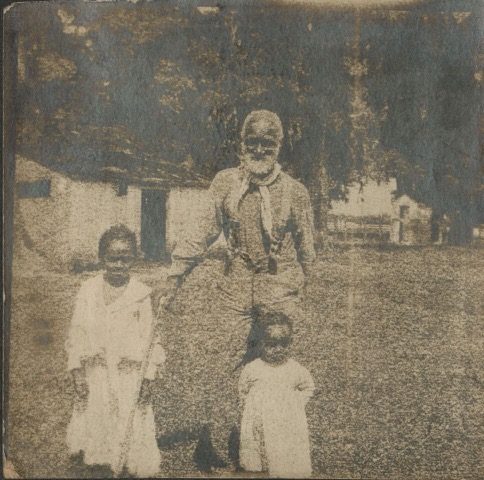

Courtesy of the Georgetown Memory Project

Frank Campbell, one of the 272 enslaved people sold in 1838, is photographed here in 1906, still working on a plantation in Southern Louisiana.

A hundred and six miles and worlds away from the urban landscape of New Orleans and Tulane University sits Maringouin, a small, rural town with a population of 1,100 and a per capita income of $10,000. According to Cellini, 900 of them are descendants of the 272 enslaved people sold to Southern Louisiana plantations in 1838.

Among the 900 are Thomas’ grandfather and Harper Royal’s grandmother. Also included in the 900 are descendants of Frank Campbell, one of the 272 enslaved people sold by Georgetown. The Georgetown Memory Project located a photo of Campbell, who was 24 when he was sold to a sugar plantation in Terrebonne Parish and 96 when the photo was taken, still working on a sugar plantation.

GMP has since located 359 of Campbell’s descendants, many of whom live, in Cellini’s words, “exactly 150 feet from the property line of that sugar plantation.”

“The people who built our university and their descendants are exactly where we left them in 1838,” Cellini said.

For the people of Maringouin, many of whom lack access to basic services, legacy status at Georgetown may not be an adequate measure to address the legacies of enslavement.

“Maringouin is pretty rural, it’s a country town. A lot of people live in poverty,” Thomas said. “But I definitely feel like legacy status isn’t enough … just because I took the opportunity to get an education and further my degree doesn’t mean that’s what everybody wants for them, and every other descendent is owed just as much as I am … But I do think it is a step in the right direction.”

Courtesy of the Georgetown Memory Project

Descendants gather in autumn on 2016 in Maringouin, LA. The descendants hold the broken gravestone of their GU272 ancestor, Cornelius Hawkins, retrieved from a nearby churchyard.

“You can’t really know your future until you know your past”

Though legacy status grants the descendants preferential consideration in the admissions process, it does not guarantee acceptance to the university, nor does it provide for financial aid. The average cost of attendance for a Georgetown undergraduate student attending the institution in the 2017-18 school year is $72,496 a year.

While Thomas wanted to attend Georgetown, she needed to raise the funds necessary to afford the tuition and fees and started a Go-Fund-Me campaign when she was notified of her acceptance.

“When they offered legacy status, I definitely decided then and there that I wanted to take the opportunity to go to Georgetown and to experience first hand where I’m from and where I have been … You can’t really know your future until you know your past,” Thomas said.

Short-Colomb pointed out, however, that not all descendants of the 272 see legacy status as particularly beneficial to them.

“So if you’re not coming to go to the School of Foreign Service or to business school or the broad-based liberal arts, Catholic university education, what actually [does Georgetown] have to offer to students from Maringouin, Louisiana?” Short-Colomb said.

The decision to offer legacy status to descendants was made by the Georgetown working group, without participation from or consideration by the descendants themselves. Cellini said he offered to connect the working group with the descendants GMP was finding, but he was turned down multiple times.

“I think at the very least, there should be a way for Georgetown to ensure that the descendants of those 272 enslaved people never have to worry about if their college education is going to be paid for, Georgetown or any other place of their choosing, because after all, it was slave labor that kept Georgetown afloat,” Harper Royal said.

With a history rooted in enslavement, monetary cost is not the only concern raised by some of those affected.

“[Some of the descendants] feel like this is an opportunity for them to right a wrong. For me to get an education from an institution that my mama couldn’t even walk across the campus with,” Carolyn Barber-Pierre, Tulane assistant vice president of student affairs and the head of Office of Multicultural Affairs said. “You know, does it show progress? Do I forget the history? No. You will never forget the history. But you can’t live in the past. You can right the wrongs, you can change the culture.”

“What would Tulane do?”

Tulane cannot trace any part of its history to a single sale or direct evidence of slave ownership. Rather, members of the Tulane community and descendants alike task it with holding itself accountable for the more nuanced history that underscores the charter’s allowance for educating the city’s “white young persons.”

University-led initiatives to increase diversity have sought to heal Tulane’s history of racial exclusion. Some believe, however, that repairing a history of racial oppression goes beyond admitting more students of color.

“It’s one thing to get accepted, it’s another thing that you can successfully matriculate to the environment in your tenure here,” Barber-Pierre said. “… Do you bring the numbers then change the environment? You gotta do both at the same time.”

One initiative that has been suggested is the development of a curriculum related to what it means to be an institution established in the American antebellum South, both for students and for New Orleanians.

“I know having gone to school in New Orleans, and as a child, I never got a true history of what New Orleans was to the slave industry, being a black person,” Harper Royal said. “I was never taught until I taught myself.”

For Tulane student organizers like Sydney Monix, a New Orleans native and Students Organizing Against Racism executive board member, Tulane must prioritize the public acknowledgment of its potential ties to slavery.

“Tulane has a moral obligation to accept and admit its history, past and present contributions to racism …” Monix said.

In the eyes of Monix and others, Tulane must now take what Georgetown took 18 months ago: a first step.

“I can say this … if Tulane does not want to find slaves that were associated with the university and their descendants, it almost certainly won’t,” Cellini said. “But if it does want to find those slaves and their descendants, it actually might. But you know the key moment is that intentionality at the beginning.”

As Adderley said, Tulane was founded in a city with one of the largest slave trade ports in the world, at a time when the United States was dependent on the labor of enslaved people.

“To be the leading, wealthiest research institution in that city, founded at the height of that blood-soaked wealth, what could we do to lead?” Adderley asked. “What would Tulane do?”

An abridged version of this article ran in the Oct. 19 print edition of The Hullabaloo.

Winston Otillio • Jun 22, 2020 at 10:09 pm

I agree with the final statement. If something could have been found linking tulane to slavery it would have been found thru extensive research. Tulane is very integrated & it only sounds like they are trying to stir an empty pot.

TCO • Dec 1, 2017 at 11:40 am

I really don’t understand this article at all. It opens up as if the article will be about racial injustices Tulane has committed, continues to spend a majority of the article talking about Georgetown, a university that has no financial or connections otherwise to Tulane, and finishes with a call that Tulane, “must prioritize the public acknowledgment of its potential ties to slavery.” What? Even though Tulane has spent money, time, and resources to research any possible connection it has had to slavery, after finding none (which the article even admits “Tulane cannot trace any part of its history to a single sale or direct evidence of slave ownership”) they have to acknowledge that they MIGHT have had potential ties to slavery? I do not understand how you could want Tulane to take accountability for something it did not do because another university did do something bad? Should every student at Tulane walk into the conduct office to admit its “potential ties to cheating” because another student in his or her class cheated on an exam? Your logic here is extremely flawed.

Furthermore, I would implore the Hullabaloo to please stop with clickbait titles that make insinuations that are not true ““What happened to the people”: 1838 sale of 272 people challenges universities to evaluate ties to enslavement” certainly makes it sound like Tulane has ties to enslavement despite clear indications later in the article they do not. Sensationalism b.s. journalism at its worst.

Ann Case • Oct 20, 2017 at 10:43 am

The university was established as the Medical College of Louisiana, and then the University of Louisiana, long before it was Tulane University of Louisiana. Research has been conducted to find any slaves associated with the establishment of these universities, but none have been located – per William Jones’ thesis research, among others’. Everyone is welcome to continue the research.