Your donation will support the student journalists of Tulane University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Pay to play

March 16, 2017

“We do have hungry nights that we don’t have enough money to get food in,” former UConn guard and current Portland Trailblazer Shabazz Napier said in a post-game interview in 2014. “Sometimes, there’s hungry nights where I’m not able to eat, … but I still gotta play up to my capabilities.”

Napier is not alone in his struggles. Former Houston Texans running back Arian Foster dealt with food insecurity while playing at University of Tennessee. Foster admitted in the 2013 documentary “Schooled: The Price of College Sports” that he received extra payments to afford food and pay rent. Despite knowing he was breaking NCAA rules, he continued to accept the money out of necessity.

Foster also believes the NCAA does value the players, and that payment should be a part of the student-athlete role.

“[The NCAA has] us hoodwinked into thinking taking money is wrong as a college athlete,” Foster said in an interview with ESPN. “It’s wrong for us, but it’s not wrong for them. I guarantee every NCAA official has a [BMW] or [Mercedes]-Benz or something. That’s not wrong, but it’s wrong for me to get $20 to get something to eat?”

Critics of player payment, however, believe the scholarship and room and board are the compensation.

“They’re not professional athletes,” NCAA chief Mark Emmert said in an interview with CNBC. “They’re not what some people are arguing they should become, which is unionized employees of the university.”

Foster believes a degree is not fair compensation when considering how much work athletes put into their respective program.

The NCAA brings in $6 billion yearly and more than $1 billion from March Madness alone. The association also has a $10.8 billion March Madness contract with CBS/Turner Sports through 2024.

Building resentment and a 2013 court ruling led to the NCAA creating a middle ground.

In 2015, the NCAA changed its scholarship system to base scholarships on the total cost of attendance of an institution. This allowed schools to give complete room and board packages and cash stipends to cover costs of daily things including snacks and student fees.

One major reason behind the changes was the 2013 antitrust class action lawsuit O’Bannon v. NCAA. The lawsuit filed by former UCLA basketball player Ed O’Bannon centered around the association’s use of student-athlete images for commercial use. The lawsuit argued players are entitled to financial compensation after graduation.

On June 6, 2013, District Judge Claudia Wilken found the NCAA in violation of antitrust laws.

The O’Bannon case altered the NCAA. After Wilken’s decision, the NCAA implemented a stipend program to benefit athletes.

The scholarship athletes receive covers the full cost of attendance, as designated by the financial aid office. The stipend that athletes would receive is the difference between the cost of attendance determined by the school and actual cost.

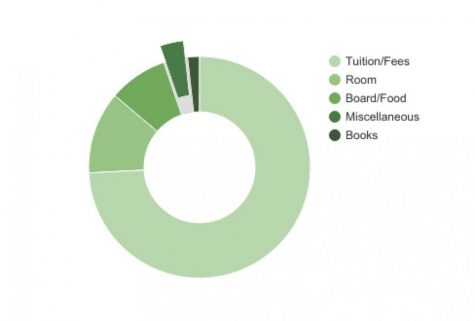

“The part of [spending money] is in the part of the scholarship titled ‘miscellaneous,’ and that’s the one that was just added to the NCAA rules about three years ago, and it’s referred to as the cost of attendance,” Tulane’s NCAA Compliance Assistant Provost Jason Gray said. “So that’s the number that’s the gap between tuition, room, board, books, fees, up to what the financial aid office determines to be full cost of attendance.”

At Tulane, the total cost of attendance for an incoming freshman is $67,114, but the gap in actual cost is around $2,400 as of 2015. Gray also said that the Office of Financial Aid would re-analyze the cost of attendance every three to four years, meaning there will likely be a new number for the 2017-18 academic year. Full scholarship students, according to Gray, currently receive $2,400 throughout the year.

While not ideal, the stipend is adequate for Samir Sehic, a sophomore forward on the Tulane men’s basketball team.

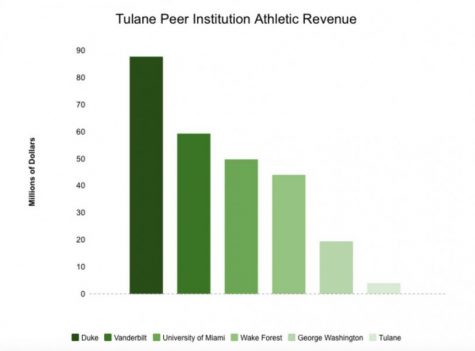

Sehic spent the first year of his collegiate career at Vanderbilt, where he played in 22 games as a freshman during the 2015-16 season and averaged 1.2 points per game. The transfer to Tulane brought more than just a change of scenery. It also decreased the money he received.

“From my changes of school, being at Vanderbilt last year, to now at Tulane, the stipend has lowered,” Sehic said. “… But I would still say that it is enough.”

The stipends are available at most of the major sports programs and range from around $2,000 to $5,000 a year, but some schools are offering more, according to CNN Money. National College Players Association President Ramogi Huma, said he believes the stipend “is a modest amount, but it’s definite solid progress” in a CNN Money article.

Due to no set guideline for the total value of stipends, athletic compliance programs work with the university’s financial aid office. With the cost of attendance depending on the institution, coaches and prospective players look at the “miscellaneous” category that this money falls under as another part of the scholarship.

“When it first came around, I had some trouble explaining to my coaches, who had been around for a while, and I said ‘look you’ve got to just consider this as room or board, it’s just this percentage. Room and board is part of the scholarship number, and it’s about 10 [percent]. This is the same thing but it’s about 8 [percent],” Gray said.

Most student-athletes are content that there is any form of compensation.

“I would say overall it is enough. … Of course, like every college athlete, we’d be willing to take more and be happy to take more, but I would say that it is enough,” Sehic said. “I don’t think it’s a bare minimum either. I think it’s above a bare minimum and I think it does the job that it’s supposed to.”

Image by Emily Meyer

Image by Emily Meyer

Gray and others involved in athletics administration are satisfied with the program, but critics do not see it as an improvement.

“I believe it will all break down inevitably due to the hypocrisy of it,” O’Bannon’s attorney William Isaacson said. “The NCAA says everything about basketball, football and college sports is professional except the athletes. It is a completely professionally-run business making billions of dollars. That hypocrisy is going to break down slowly.”

Within the NCAA, players no longer go hungry or take money despite breaking NCAA codes of conduct, but the pay-for-play debate remains the most controversial issue. While the scholarship stipend revolutionized past NCAA regulations, full pay is not on the horizon, according to Emmert.

“One of the most fundamental principles of intercollegiate athletics is that these are students who happen to be athletes — not the other way around.”

Leave a Comment