What Latinidad means at a predominantly white institution

“When I teach Latino studies, normally the first three weeks of the course is dedicated to what does it mean to be Latino, what does that mean? What does Latino/Hispanic mean and what is the differentiation. Latinidad. What does that mean?” Professor Isabel Caballero said.

According to Caballero, a professor of practice in the Tulane University Department of Spanish and Portuguese, Latinx identity in the U.S., or Latinidad, is a complex political and cultural term that roots itself in a sense of unity for people of Latin American origin living in the U.S. Encompassing over 20 countries*, a multitude of cultures, races and social classes, Latinidad can be an extremely difficult and confusing concept to grasp, even for Latinxs themselves.

Despite having a term to unify the largest minority group in the U.S., there is no set mold of what a Latinx is. Though there are stereotypes of what a Latinx person looks like (brown skin, dark hair, short height, etc.), due to the many intersections of race, gender, sexuality and more, anyone can be Latinx. This complexity of identity is something Caballero engages students in conversation with regularly.

“Trying to explain all of that and that it’s different for people in each group is really difficult and exhausting and more exhausting for them than for me I think,” Caballero said.

What it means to be Latinx can vary from person to person, and is also dependent on the context of time and place. Being Latinx in the South today can be different from what it meant to be Latinx in New York City three decades ago. The Latinx experience at Tulane is no exception, as it frequently prompts discussion among Latinx Tulane students of the past and present.

“Celebrating our culture, no matter who’s there”

Despite being one of the largest minority groups in the country, Latinxs remain one of the most underrepresented groups on Tulane’s campus. According to the Office of the University Registrar, 6.76 percent of students enrolled in Newcomb-Tulane College for the fall of 2017 identified as Hispanic.

With small numbers and stratified identities, one of the ways students have tried to make sense of their Latinidad on Tulane’s predominantly white campus is through the creation of student organizations, like Tulane University Gente, formerly known at Generating Excellence Now and Tomorrow in Education (GENTE).

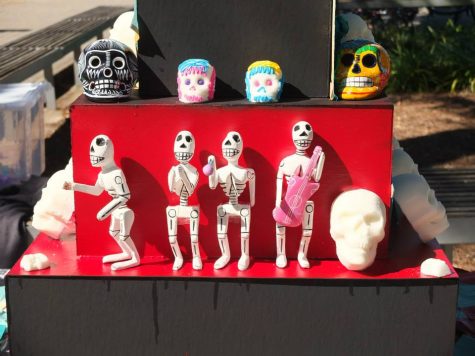

Tulane Gente members in front of the annual Dia de los Muertos Ofrenda 2014. TU Gente’s programming focuses on educating the greater Tulane community about Latinx traditions.

Efren López, co-founder of TU Gente and Tulane alumnus ‘15, said the organization was created with the intent of educating the Tulane community about Latinx culture, in addition to providing a safe space for Latinx students to be themselves. Though the name was created in many ways as a pun to spell out the Spanish word for “people,” education in the Latinx community at Tulane is something López feels was important to include.

“The emphasis on education was also a major key to what we wanted to showcase rather than create nothing more than a display of ‘food and culture,’” Efren López said. “We wanted to make sure people (the greater Tulane community) knew that Latinos could excel in education, first and foremost.”

Programming has always served as a vital way for TU Gente to accomplish its mission of educating the community. One of the more notable events put on by TU Gente, López recalls, was the first Dia de Los Muertos ofrenda that was built by members of TU Gente.

Día de Los Muertos, or Day of the Dead, is a holiday celebrated most notably in Mexico and other Latin American countries as a way of paying tribute to deceased family members. Every year, an ofrenda, or altar, is constructed and pictures of the dead as well as offerings like pan dulce, water and flowers are placed on it to pay homage to the dead.

“We dedicated it to the stories of Latinos who had taken their lives in higher ed across the U.S.,” López said. “The idea was to educate the greater Tulane population on what certain folks do for day of the dead and why it’s important.”

Like the ofrenda, programing put on by TU Gente is dedicated to educating the greater Tulane community about different traditions within Latinx cultures. Nearly 10 years after its founding, the current executive board of TU Gente has kept the same mission.

“We are getting a lot of people showing up to events who aren’t in the Latino community but want to share in our culture,” Roberto Santiago, TU Gente co-president and junior said. “And I feel like that’s extremely important because GENTE has always been about celebrating our culture, no matter who’s there.”

“They didn’t care about Latinx students”

Tulane continues to be a predominantly-white institution, and throughout its history, there have been several instances in which some students of color were made to feel unwelcome into the campus environment. Latinx students are no exception.

In April of 2016, Kappa Alpha Order Fraternity constructed a wall of sandbags around the perimeter of their fraternity house, with graffiti on the wall that said “Make America Great Again,” and “Trump.” The fraternity eventually dismantled the wall after hearing critiques and negative feedback, which they responded to by suggesting their actions were meant to be taken as a joke.

Tulane chose to side with KA and sent out an email that reaffirmed KA’s right to free speech. Some Latinx students, however, including members of TU Gente in particular, expressed concern over the event, saying they felt it was a racially motivated incident.

“Me and the other TU Gente members felt like we couldn’t leave our room and walk around campus; we felt unsafe and targeted,” Gonzalez said. “For two weeks after that, I spent every single moment I wasn’t in class at the Office of Multicultural Affairs, the only safe space we could find on campus.”

Gonzalez is not alone in this struggle. The high-intensity environment of a university setting coupled with being marginalized group on campus has been linked to Latinxs’ completion of college, and it isn’t only Tulane. According to Pew Research Center, only 15 percent of adults ages 25-29 with a bachelor’s degree are Hispanic, the lowest group out of all races and ethnicities.

“The message that the school was sending was that they didn’t care about Latinx students, our concerns, or our safety,” Diana Gonzalez, former TU Gente president and Tulane alumnus, said.

“The Problem with the Word”

With such a multiplicity of identities included within Latinidad, organizations that cater to all Latinxs, like TU Gente, struggle at times to reflect so many different experiences and backgrounds into their programming.

“That’s the problem with the word … even ‘Latino’ is not enough because it erases these specific nationalities, immigration experiences, race and social class, and how all of those intersections affect your experience here in the United States,” Caballero said.

One of the typical challenges faced in pan-Latinx spaces is Mexico-centrism, or the prioritization of Mexican culture, identity and people and erasure of others. According to López, this was one of the initial hurdles TU Gente sought to combat.

“At first I remember thinking that the name was corny, having come from California and being around groups like MEChA and LASA, but after learning that the name was specifically chosen to not include a specific [Latinx] identity … and focus on the greater community, I was on board,” López said.

Other difficulties range from machismo (sexism) to homophobia to colorism that can occur in the Latinx community. Though Tulane’s Latinx community is not devoid of these issues, some students feel the small size of the community offers Latinxs a unique opportunity for coalition building in spite of these systems of oppression.

“I wouldn’t necessarily say there’s less of it but more in the fact that we’re more willing to put it aside because we know that there are so few of us that we want to keep our friendships,” Santiago said.

Latinxs Unidxs

Gonzalez shares López’s sentiments about TU Gente and Latinx student organizing at Tulane. When it comes to building community, the best way to do so according to Gonzalez is by securing the longevity for student organizations.

“Never stop asking for more resources,” Gonzalez said. “Never stop asking for a seat at the table. Never stop asking for more money for your organizations. Always demand more — we deserve it.”

Ultimately, Latinidad and figuring out what exactly it means is at the center of Latinx experience at Tulane for many students. In the same way Latinxs come in all shades and experiences, the definition of Latinidad can differ from person to person.

When asked what Latinidad meant to him, Santiago answered with a warm smile.

“It’s just embracing me as a person,” Santiago said. “I am a bisexual Latino man living in America, and I eat all sorts of food including baked ziti, carne guisada, ropa vieja, arroz con pollo. It’s just me expressing my culture the best I can.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of Tulane University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.