New California bill changes state of amateurism in college athletics

Hanson Dai | Art Director

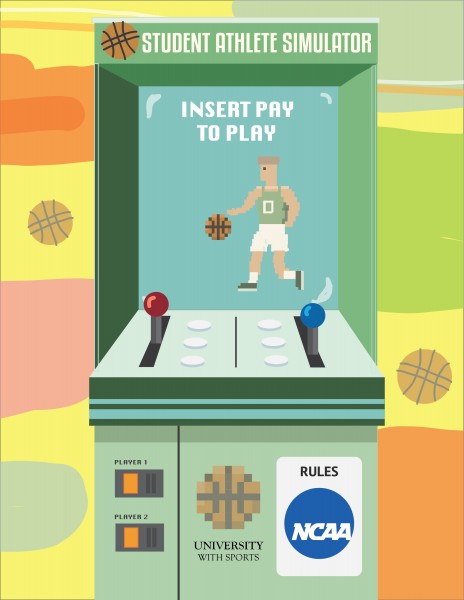

Since its inception in 1906, the role of the National Collegiate Athletic Association, or NCAA, has been to maintain the integrity of intercollegiate athletics through the creation and enforcement of competition and eligibility rules. Today, the NCAA regulates the athletic departments of 1,117 colleges and universities, approximately 500,000 student-athletes, 19,750 teams and 24 sports.

One of the primary interests of the NCAA is to ensure all of its athletes are competing as amateurs and not as professionals. Many of the ways student-athletes can be deemed as professionals mainly have to do with receiving compensation, such as student athletes being paid by their team to compete, being represented by an agent and by promoting companies and products.

In lieu of receiving compensation for competing in collegiate athletics, most student-athletes may only receive an athletic or academic scholarship covering “tuition and fees, room, board and course-related books.”

While student-athletes are not allowed to be compensated for competing outside of scholarships, many of the universities they represent reap massive sums of money annually due to their athletic programs. In the 2015-16 school year, the athletic departments of 24 universities brought in over $100 million, with the top two schools, Texas A&M University and the University of Texas at Austin, earning over $192 million and $183 million respectively.

Because the goal of college athletics is for student-athletes to compete as amateurs and not professionals, it is important that these student-athletes do not become de facto employees of their respective college or university.

As a result of this goal and the amount of money that student-athletes earn for their schools, there has been a public outcry for athletes to be compensated but also remain as amateurs. This outcry sparked legislators to take action. In February 2019, California Senator Nancy Skinner introduced SB-206, better known as the “Fair Pay to Play Act,” to the California State Senate.

The bill featured three critical components. Firstly, the bill prevents “postsecondary educational institutions except community colleges, and every athletic association, conference, or other group or organization with authority over intercollegiate athletics, from providing a prospective intercollegiate student athlete with compensation for use of the athlete’s name, image, or likeness.”

Secondly, the bill requires “professional representation obtained by student athletes to be from persons licensed by the state.” Finally, the bill prohibits “the revocation of a student’s scholarship as a result of earning compensation or obtaining legal representation as authorized under these provisions.” On Sept. 30th, 2019, Governor Gavin Newsom signed the bill into law, and it will go into effect in 2023.

Lawmakers in other states such as Florida, New York, and Illinois are planning to introduce similar bills. There is also talk of creating similar legislation on the federal level.

In response to California SB-206 and potential future legislation, the NCAA’s Board of Governors announced that it will begin to “permit students participating in athletics the opportunity to benefit from the use of their name, image and likeness in a manner consistent with the collegiate model” on Oct. 29, 2019.

The NCAA plans to gather feedback through April on how best to respond to the state and federal legislative environment and to refine its recommendations on the principles and regulatory framework. The NCAA will begin to create new rules immediately, and all rules will be set by January 2021.

While only a handful of NCAA sports are actually profitable, allowing student-athletes to be paid for their likeness could potentially help athletes in non-profitable sports, particularly female athletes. Student-athletes in non-revenue sports are far less likely to become professionals, so paying athletes in college would allow them the opportunity to make money in college.

This is best exemplified by former Stanford University swimmer, Katie Ledecky. Ledecky, a two-time national champion and six-time Olympic medalist at Stanford, was forced to forfeit her NCAA eligibility to sign a $7 million endorsement deal with swimwear company TYR.

Allowing collegiate athletes to be paid for their name, image, or likeness could potentially have monumental effects on college athletics. It will be interesting to follow the developments of the NCAA and other parties in this regard over the next few years.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Tulane University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.