Coronavirus should compel U.S. to reassess disaster readiness

The 170 confirmed coronavirus fatalities in China and subsequent response constitutes the largest quarantine in modern public health history. Were this epidemic taking place within our borders, would the United States be prepared to respond adequately?

Especially in Louisiana, our federal government’s inability to handle climate change, natural disasters and the myriad other problems our state and country is sure to face in future years must force a reevaluation of protocol.

In China, with more than 7,700 people infected, the country’s quarantine currently contains 35 million residents in 14 cities. China’s quick reinforcements such as the quarantine and push for erecting a new, specially quarantined hospital with 1,000 beds in 10 days are appropriate and proportional.

While the effectiveness of such a drastic solution is not guaranteed, a health epidemic of this scale requires an equally powerful response. This sort of response is unfamiliar and even looked down upon by U.S. public health officials due to the impracticability of family separation, halting travel and closing businesses. Even in the most severe case of a “Category 5” outbreak, the CDC recommends nothing larger than voluntary isolation at home.

This modest advisory is a revealing reflection of how the U.S. tackles crises, continuously scrambling for a cure rather than investing in prevention. If lawmakers currently do not have reinforcements in place in the case of a severe outbreak, can they be relied on for other crises, such as hurricane preparedness in Louisiana or the impending damage of climate change on the Gulf Coast?

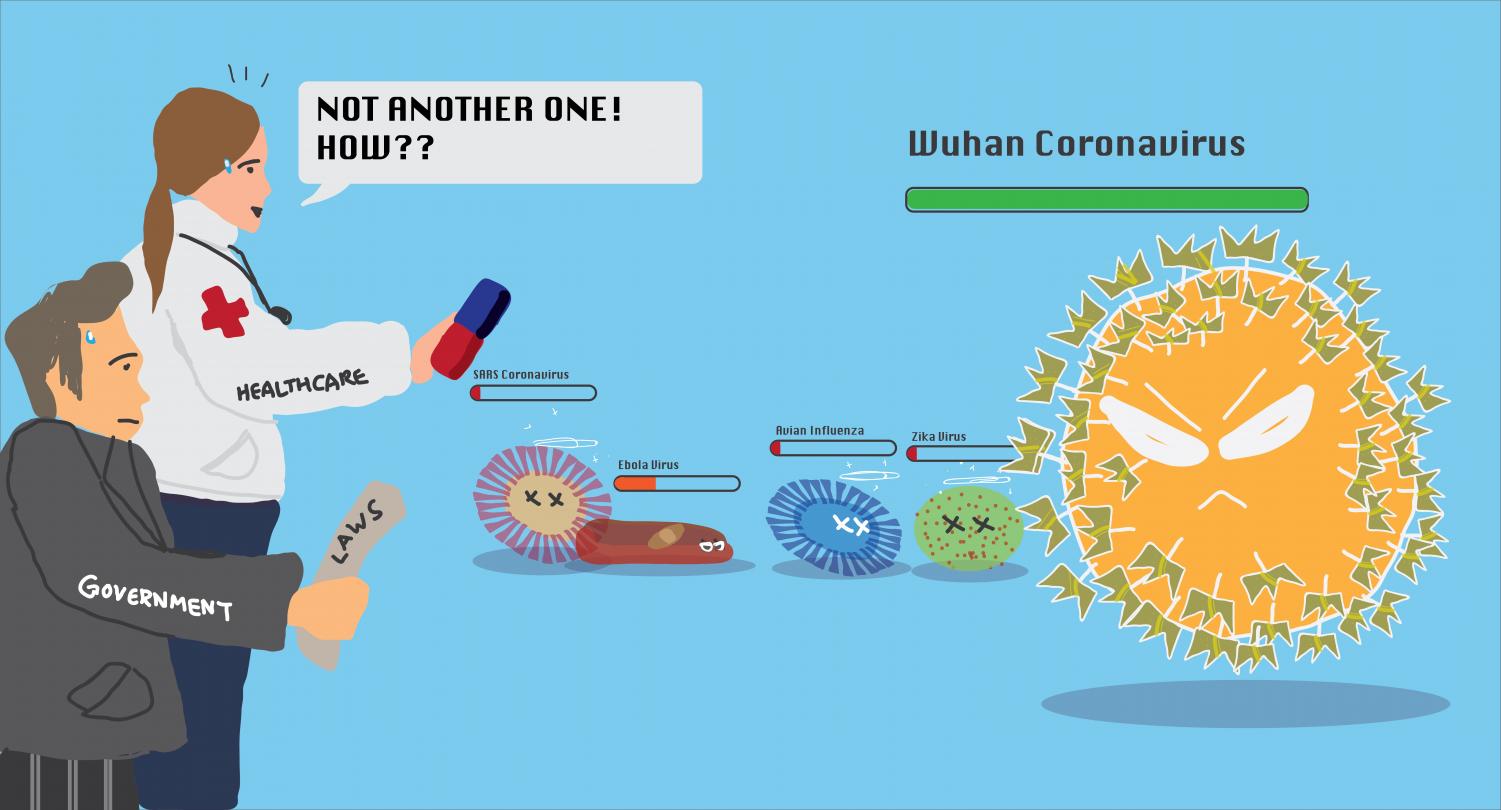

Coronavirus is a chilling reminder of a pandemic that occurred not too long ago. In 2003, severe acute respiratory syndrome emerged in Guangdong, China, from a market of livestock held in cramped, unsanitary quarters. The danger to humans is posed when a variety of animals are packed together, giving a virus the ability to adapt to many hosts, including the humans that work with the animals. The SARS epidemic should have eliminated live markets altogether.

The U.S. is no exception in failing to gain insight from public health history. The dismissal of quarantines for extreme cases is a concern, but the current methods emergency rooms use is far more worrisome. Infection control is weakly enforced in most hospitals in the nation. Sterilizing equipment, hand-washing, consistently wearing masks and giving coughing patients masks are not stringent practices.

The coronavirus can be contracted from keyboards and doorknobs. Current emergency room responses to infectious disease in the U.S. do not match the pervasiveness of the coronavirus. The SARS epidemic made it clear enough how essential immediate containment of contagious patients is when Ontario, Canada’s lack of emergency room sanitation enforcement resulted in 77% of SARS patients contracting the illness in a hospital. History should not have to keep repeating itself.

A memorable example of unpreparedness in the U.S. is Hurricane Katrina, which revealed local and federal governments’ lack of capacity to adequately handle disaster relief. One of the most appalling insight stemming from the failures after Katrina is that the government had been prepared for such a disaster only a year prior.

A simulation exercise called Hurricane Pam was organized by FEMA in 2004, gathering 300 local, state and federal government officials to participate in the disaster relief of a mock Category 3 hurricane. These lawmakers were aware of the probability of a natural disaster of this scale occurring and were given tools and extensive training to minimize the damage.

One year after the exercise, Katrina struck Louisiana, and it was apparent that the government had not fully grasped the lessons that were meant to be learned from Hurricane Pam.

Recent preventable disasters paint a disheartening vision of the future. If the federal government does not have the foresight to prepare for these types of events beforehand, it is unclear whether local governments can be relied on to adequately respond to natural disasters.

It seems even more unlikely that the climate crisis, something that has never been seen before, will be met with enough serious action. The urgency of avoiding an even bigger climate crisis before it arises is undeniable in Louisiana, and the state government already has in place a 50-year plan to restore the coastline and protect it from further erosion with looming sea-level rises. Tulane has pledged to be carbon neutral by 2050.

These efforts are commendable but will fall short if predictive maps prove true.

The coronavirus has understandably triggered a great deal of finger-pointing, but the only solution to avoiding this series of pandemics and natural disaster destruction is to look back on and correct past mistakes. As for the impending climate crisis, government officials should use this time to understand the difference proactivity can make.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Tulane University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.