OPINION | Virtual service learning falls short of its mission

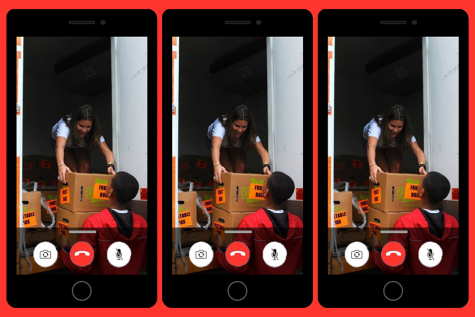

In spite of the chaos of COVID-19, service learning courses at Tulane are still being offered — virtually or with a shift towards “community-engaged learning.” Despite the obvious limitations, virtual service learning courses have been well-designed to accommodate rigid pandemic limitations, and the professors organizing them have worked tirelessly to do so. But the purpose and value of service learning, building connections and solidarity with a local community, has been diluted in the process.

Tulane students are required to take a tier-1 and a tier-2 service learning classes before graduation, which are offered as additional components for a variety of standard courses offered each semester.

Service learning classes are prided for their “learning by doing” design, where students are encouraged to engage in public service in an academic context and better comprehend a community’s needs through civic engagement. Examples of service learning range from tutoring adults English as a second language to preparing healthy school lunches. To ensure both online and on-campus students can fulfill their service learning requirements for graduation, the university has allowed these courses for the fall semester.

Just as social distancing and pandemic restrictions have dampened the college experience, these adaptations for service learning courses have diluted their value. The enriching and immersive learning experiences from last year have been exchanged for Zoom meetings and mundane assignments.

Digitizing the community engagement experience does not enable a student to fully comprehend community issues, as these can only fully be understood in the in-person, physically nearby interactions with others.

It is much more difficult to empathize with a community’s struggles, to realize why one’s service makes a difference and to develop a sense of fellowship with marginalized groups through a laptop screen.

One instance of this is the Cell 1010 service learning course this semester. Instead of “taking water samples in designated areas of New Orleans to monitor the health of the local water ecology system” as previously planned, the cohort was constrained to analyzing past water sample collection and extrapolating conclusions from unorganized datasets. It is not the same experience.

Getting lost in thousands upon thousands of cells in a spreadsheet hoping to find one telltale pattern to present, for instance, is distanced from the intimate experience of working with community partners face-to-face.

Even the simple act of lifting buckets of muddy water out of the Audubon Lagoon or visiting the community partner’s main site, both of which were part of the original plan, develops an intrinsic sense of fellowship with one’s community and one’s peers that cannot easily be replicated.

In these circumstances, it is impossible to replicate the full service learning experience safely, and sacrifices made for public health concerns are well worth it. There is still plenty of room for improvement in these courses, however — something to keep in mind if the pandemic continues into the spring semester.

As for those enrolled in service learning this semester, the service learning experience doesn’t have to end in November. Perhaps when the pandemic has withered, professors can host optional workshops for their virtual service learning alumni, to catch up on the in-person element and the intangible insights that it offers. Organizing a day trip to the intended service location site or meeting with previously tutored students could build those connections that only happen from a distance less than six feet away from each other.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Tulane University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.