Stephen Martin Sr.: Trailblazer on, off diamond

On April 3, 1965, Stephen Martin Sr., a freshman at Tulane University, broke the color barrier in the Southeastern Conference against LSU. While Martin Sr. had a monumental impact on sports that day, his impact after leaving the diamond is greater.

A native of nearby Marrero, Louisiana, Martin attended St. Augustine High School in New Orleans, graduating in the class of 1964 as a four-year letterman, honor student and recipient of the Purple Knight Award.

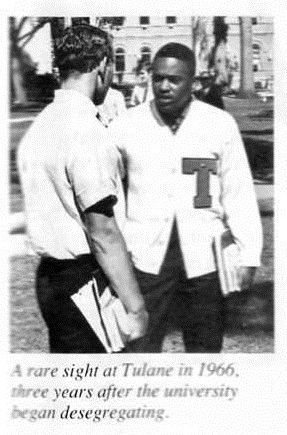

With the support of his high school principal, who sought to land Black students at top universities, Martin attended Tulane on an academic scholarship and was a member of the second class of Black students that attended the University.

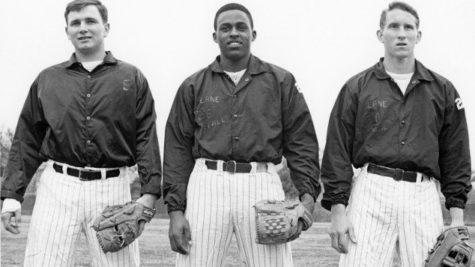

At Tulane, Martin was recruited by baseball head coach Ben Abadie, and in 1964, he tried out for and made Tulane’s freshman baseball team. On April 3, 1965, Martin made his debut against the rival LSU Tigers, becoming the first Black athlete to compete in any sport on any level of competition in the SEC. Martin recorded a sacrifice fly and a single as Tulane split a double-header with the Tigers in his first appearance.

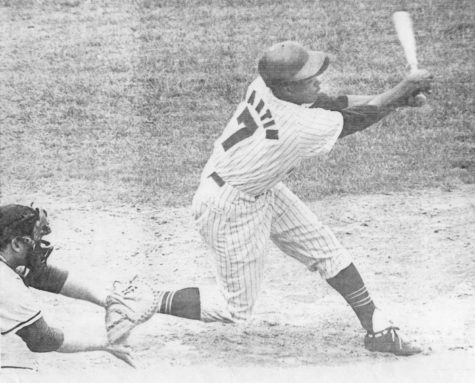

As a sophomore in 1966, Martin made his varsity debut for the Green Wave in the team’s season opener against Spring Hill. At the varsity level, Martin competed in 61 career games for the Green Wave, with a batting average of .230 to go along with five home runs, 15 RBIs and a perfect four-for-four on stolen base attempts.

In 1966, Tulane’s Board of Trustees decided to leave the SEC, but not before Martin made history in the top conference in college athletics. As a result of Tulane’s departure, however, Martin’s story is largely a forgotten part of SEC history.

Instead, other pioneers such as Vanderbilt University’s Perry Wallace, who became the conference’s first scholarship basketball athlete in 1967, and Kentucky Wildcat Nate Northington, who became the first Black student-athlete to compete in an SEC football game, receive most of the attention.

Despite his lack of recognition, Martin endured the same hardships as those other men and others in the Black community at the time. Martin was not treated fairly by all of his own teammates. Some refused to speak to him, while others did not know how to feel about him being on their team. Some teammates did befriend him and tried to give him a positive experience.

Abadie himself often faced threats for having Martin on the team and had to protect Martin from death threats when the team traveled throughout the deep south.

Martin played centerfield, and he was too far away for his other teammates to help him while on the field, if they even cared. As a result, Abadie had to hold Martin out of certain games. Martin’s statistics were also limited due to racial tensions during the era in which he played.

“My dad didn’t play certain games that year. So, his statistics when you look at them are somewhat average. Not because he’s an average player. It was because he was Black, and decisions were made that were in his safety interest,” said his son Stephen Martin Jr. “Sometimes my dad knew, sometimes my dad didn’t know … You look back and in and I think … he had a fair shake at playing in the SEC, my dad would have been in the Hall of Fame for the SEC easily.”

In fact, Martin Sr.’s best sport upon coming to Tulane was not baseball. His “passion sport” was football, and he was named Outstanding Player of the Year in New Orleans during high school. However, Tulane’s athletic department recommended that he refrain from playing football for his own safety.

Despite the school’s recommendation that the football field was too unsafe, Martin Sr. was still a target on the baseball diamond. He was forced to play under the stress that anything could happen to him. While he was never physically attacked, he faced constant vile heckling from spectators during games.

Martin Sr. never even intended to break the SEC’s color barrier when he became a Tulane student. His only goal was to excel academically, and he graduated as a Rockefeller Scholar in 1968 with a Bachelor of Science in Latin with a minor in mathematics.

“I consider him one of the silent civil rights warriors,” Martin Jr. said. “My dad fully knew that he was going to be one of other students in the desegregation of Tulane’s campus, but now my dad had this larger mission he was a part of.”

After graduating, he was drafted into the United States Army and was honorably discharged. Although Martin Sr. was invited to play Minor League Baseball, he instead returned to Tulane and received his Master of Business Administration as an Arthur Young Scholar in 1973.

“My father believed that education has many Blacks during that time, and even today, Black families, that education was the upward mobility that education was the upward mobility that this country would not be able to take away. And so instead of pursuing that professional career, he went on to get his MBA,” Martin Jr. said.

Martin Sr. required all three of his children to reach the terminal degree in their field. Martin Jr. received both his bachelor’s and master’s at Tulane before receiving a Ph.D. in epidemiology from the University of Michigan.

Martin Sr. then used his Tulane education to become a certified public accountant, working at various accounting firms as one of the first Black CPA’s in Louisiana. In the 1980s, he joined the accounting team at McDermott International and moved with his young family to work in Brussels, Belgium.

Martin Sr. and his family later returned to the U.S. where he started his own accounting firm before establishing the internal auditing department at Tulane and serving as its director from 1991 to 1994. During this time, he helped with Tulane’s recruiting of student-athletes by talking to athletes about his experiences at Tulane.

After Martin Sr. left Tulane as an employee, he became the finance chief at Delgado Community College before becoming the vice president of Texas Wesleyan University and later an IRS agent.

In 2012, Martin landed his dream job of chief financial officer at Tuskegee University, but he was unfortunately diagnosed with mesothelioma, forcing him to retire less than a year later. He passed away on May 14, 2013.

Following his death, Martin Sr.’s family fought for his recognition by both the SEC and Tulane. Fifty years after his landmark achievement, Martin Sr. was honored by the conference during the 2015 SEC Baseball Tournament. Despite his historic achievement, he was not inducted into the Tulane Hall of Fame until 2017.

Martin Jr. continues to work with Tulane and its athletics department to not only honor his contributions on the field but also off the field.

In 2019, the Tulane athletics department established the Stephen Martin Scholars program, which “recognizes the lasting impact that individuals from diverse backgrounds have made at the university.” The program honors two Tulane athletes annually who demonstrate Martin’s most prominent traits — a high level of character and leadership while also succeeding in school and giving back to the community.

SEC Commissioner Greg Sankey provided a statement on Martin Sr.’s accomplishments. “Stephen Martin was a trailblazer in every sense of the word as the very first African-American student-athlete to compete in Southeastern Conference competition. Through his heroic determination in breaking racial barriers, he opened doors for generations of underrepresented student-athletes who came after him and he went on to serve our country with honor in the US Army. It is important for Stephen Martin to be remembered for the impactful role he played in integrating athletics in the SEC,” Sankey said.

While recognizing Martin Sr. as the first Black SEC athlete is important, it is more important to recognize the man he was off the field.

“It’s important that, across the Tulane family, from the administration, to the faculty, to the student body, that we have an opportunity to define this campus post its founder,” Martin Jr. said. “Tulane has an opportunity to get right if it commits fully around the end. And [that’s what I want] my dad’s story to be a part of — not just [something] we come back [to] every Black History Month.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of Tulane University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.