“You know me, I’m off in the cut

Always like a squirrel lookin’ for a nut

This is a fo’ sho, I’m not talkin’ ’bout luck

I’m not talking ’bout love, I’m talking ’bout luck”

Anyone driving down Broadway Street on a Friday or Saturday night will, at some point, hear lyrics from Pitbull and Ne-Yo’s hit song “Time of Our Lives” over drunk shouts and laughter emanating from the crowded front rooms of fraternity houses.

But while the infectious beat has earned the song its cultural persistence on college campuses, the sentiment might not ring as true in recent years. College students, overall, might not be “looking for a nut” like they used to.

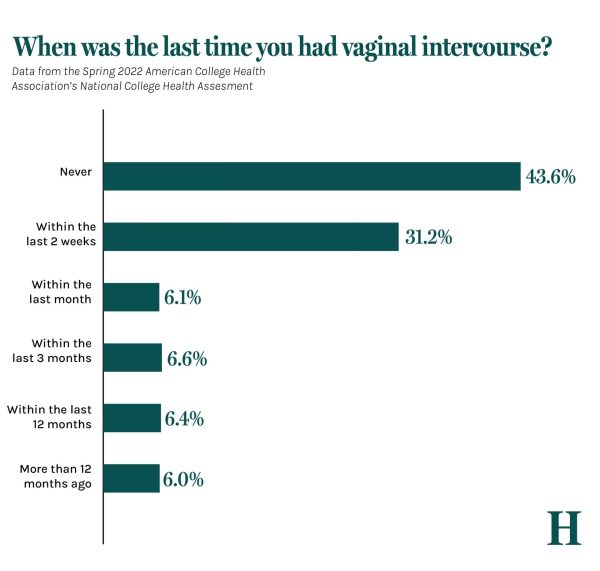

According to surveys from the National College Health Assessment, in 2022 only 37.3% of college students reported having vaginal intercourse in the past 30 days, compared to more than 50% in 2000.

In 2000, just under 30% of college students reported never having vaginal intercourse whereas two decades later, that number is above 40%.

The Atlantic, which labeled these trends as a “sex recession” in a 2009 article, suggests a few possible explanations, including students prioritizing their studies, a student body more empowered to reject sexual advances, alternative forms of pleasure and rising insecurities.

While sex may be trending downward on college campuses, hookup culture — the normalization of “uncommitted sexual encounters” — is an increasingly prevalent force, according to research from the National Institutes of Health.

Professor of sociology and author of “American Hookup: The New Culture of Sex on Campus,” Lisa Wade, theorized that hookup culture itself is suppressing sexual activity by creating an exclusive, competitive sexual culture based on physical attractiveness and expectations of emotional detachment.

Hookup culture is “based on this stereotypical idea of what men want,” Wade said. In a hookup culture, “sex should be hot but not warm and you are entitled to walk away afterward with no amount of accountability for that relationship.”

Wade said this “hardcore” culture around sex may limit ways students are able to explore sexual experiences. If the main pathway to a relationship is hooking up, students who choose not to participate in hookup culture are cutting off that opportunity to get into a relationship. This, Wade said, could also lead to less sex on a demographic level.

Despite its drawbacks, Steven Epstein, author of “The Quest for Sexual Health: How an Elusive Ideal Has Transformed Science, Politics, and Everyday Life,” said no sexual behavior can be categorically deemed unhealthy or otherwise. He said it depends on the individual and their society.

In some situations, “having a lot of sex with different partners without commitment … seems to be connected with affirmation of the self [and] resistance to stigmatization,” Epstein said. “But in other situations, it might result in lack of satisfaction and … competition.”

Compared to the school she worked at previously, Wade said hookup culture at Tulane University is “vibrant” and “thriving.” Hookup cultures are strongest at schools where a large portion of the student body lives on campus, Greek life is active and where there are high percentages of white and wealthy students, according to Wade.

At Tulane, new requirements mandate incoming students live on campus three years, 42% of students are involved in Greek life and over 60% of the student body is white. 69% of students come from the top 20% of median family income.

In a 2022 opinion article for The Hullabaloo, Jeanette McKellar wrote that hookup culture at Tulane objectifies female-identifying students, prevents emotional intimacy and prioritizes male pleasure.

Co-director of the Sexual Violence Prevention Response Collective, Anna Johnson, said there is an important distinction between rape culture and hookup culture, though lack of empathy is a part of both.

“Rape culture is the culture that rape thrives in. It forgives perpetrators. It blames victims,” Johnson said. “Whereas hookup culture is the culture that hookups thrive in. And those two things can certainly be mutually exclusive.”

Wade said students desire alternative ways to explore their sexuality, like courtship and queer experimentation, including the option to engage in uncommitted hookups. The problem is that hookup culture tells students to keep those desires secret.

Students are also probably overestimating how much their peers are actually hooking up compared to reality, as well as how much they’re drinking and partying, according to Wade.

“If every student at Tulane stood up at once and said the truth about what they really wanted, it would create critical masses of desire, where you could have multiple sexual cultures on campus competing with one another,” Wade said. Sex could be a “menu rather than one meal.”

Johnson said one way to improve the culture around sexuality at Tulane is by approaching conversations about sex with more care.

“A lot of people in our community [speak about sex] so carelessly,” Johnson said. “Consent is about caring enough about your sexual partner’s wellbeing that you’re willing to check in with them and honor them.”

In terms of sexual behaviors, Epstein said it is up to the individual to determine their healthiest way of engaging sexually, or not.

“It’s unsatisfying, but at the same time, it’s freeing” to not have one prescribed way to be sexually healthy, Epstein said. “We need to do the work of thinking through what it would mean to live our lives in a sexually healthy way, rather than just accept that there’s some standard definition that any authority can give us.”