Nearly three weeks ago, Hurricane Helene ravaged the southeastern United States, making landfall in Florida’s Gulf Coast and moving north. The storm took over 200 lives and caused damages that may total up to $250 billion. Just one week ago, Hurricane Milton swept eastward through the Florida Peninsula, where some residents were still dealing with the residual effects of Helene. Residents across the United States are crawling out of the rubble of these storms.

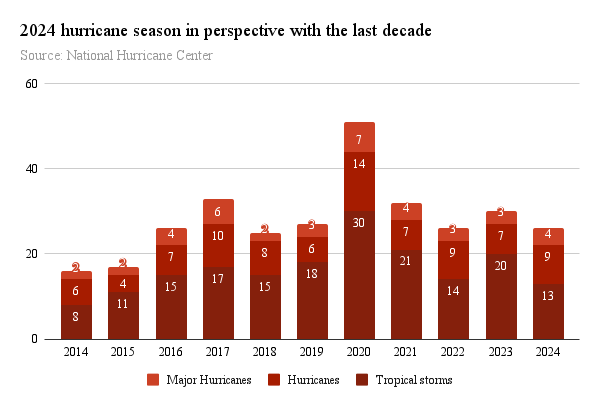

As of Oct. 15, this year has seen 13 tropical storms, nine hurricanes and four major hurricanes. In May, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration predicted that the 2024 hurricane season would see 17 to 25 named storms, of which eight to 13 would become hurricanes, including four to seven major hurricanes. Even with six weeks left in the traditional hurricane season, this season’s numbers can already be categorized as above average when compared to the 30-year average from 1991-2021.

Hurricane Beryl — a category 5 storm that passed over Grenada, the Yucatan Peninsula and eventually Louisiana, Texas and Arkansas in the first week of July — made history as one of the earliest category 5 hurricanes recorded.

Several factors contribute to this year’s particularly vengeful season, which includes one of the most deadly hurricanes in the past 50 years, second only to Hurricane Katrina: Hurricane Helene.

These conditions include warmer-than-average ocean temperatures, reduced vertical wind shear and weaker tropical Atlantic trade winds. The Atlantic Ocean basin is also experiencing one of the strongest El Niño periods on record and a transition to La Niña conditions, further reducing wind shear and conducive to hurricane development.

What else can we expect this year? According to a recent article from the Weather Channel, forecasts may be somewhat brighter moving forward. Historically, “the most favored area for tropical storms and hurricanes to form shifts westward” in October. NOAA reports that only 233 hurricanes have formed in October and just 56 in November since 1851, which works out to an average of one hurricane a month in October and even fewer in November, with the number of hurricanes actually making landfall accounting for a small fraction of these.

Despite a more hopeful outlook for the rest of the hurricane compared to what the Atlantic Basin has experienced so far, New Orleans is by no means in the clear. Hurricane Francine, a category 2 hurricane left many off-campus students without power and the streets covered in debris, is a reminder of what students and New Orleanians may expect in the case of another hurricane, which is entirely possible with a month and a half left of hurricane season.

Students can get a sense of what may happen in the case of evacuation by looking to hurricanes like Ida, which made landfall in Louisiana on Aug. 29, 2021. Students were initially instructed to shelter in place in accordance with the shelter-in-place order by the City of New Orleans, but remaining students were later evacuated by bus to Houston on Aug. 30 and Sept. 1. Campus did not return to full functioning status until Sept. 30, at which point students returned. Students can expect a similar response from the Office of Emergency Preparedness this year if necessary.

Now is the time for students to review their emergency and evacuation plans and update them in Gibson.

On Sept. 13, Gov. Jeff Landry denied a request from the Sewage and Water Board of New Orleans asking state legislators for $29 million for a new power substation to help keep the pumps running, citing “concerns about where the money will come from and how it will be used.”

What this recent news means for New Orleans in the final stretch of hurricane season is yet to be determined, but if the city has learned anything from past tragedies, it is that good infrastructure and preparation are the key to withstanding hurricanes in a city that is all too familiar with them.