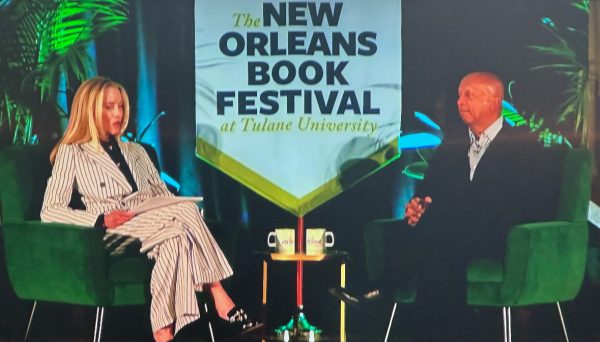

On March 27, the opening night of the New Orleans Book Festival, acclaimed lawyer and social justice advocate Bryan Stevenson took the stage for a powerful conversation. Moderated by philanthropist and Emerson Collective founder Laurene Powell Jobs, the interview brought the audience from laughter to tears in a matter of minutes.

Best known as the founder of the Equal Justice Initiative and author of the memoir “Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption,” Stevenson has spent his career fighting for the poor, the incarcerated and the condemned. But on this night, in front of a crowd of students and locals alike, he did more than just share his resume — he shared his heartfelt story.

Stevenson said that it was proximity — a term he uses often — that first changed his path. As a law student at Harvard University, he was unsure of his future. After his first year, he transferred to the John F. Kennedy School of Government but soon felt even more discouraged. “They were teaching us how to maximize benefits and minimize costs,” he said, “but it didn’t seem to matter whose benefits got maximized and whose costs got minimized.”

Then came the day he visited a death row inmate in Georgia. Stevenson was nervous and unsure of what to say. “I just started to apologize,” he said. “‘I’m so sorry, I’m just a law student, I don’t know anything about the death penalty. I don’t know anything about anything.’”

But when Stevenson delivered the news that the man wasn’t at risk of execution within the year, the inmate grabbed his hand and said, “Thank you. Thank you. Thank you … Because of you, I’m going to see my wife, I’m going to see my kids.”

The visit lasted hours. The two men were the same age, with the same birthday — and, for a moment, just two people sharing stories. “We just forgot,” Stevenson said. “I forgot that I was a law student, and he was a condemned person. We were just two people talking, and one hour turned into two hours, two hours [into three]. We lost all track of time.”

When guards stormed the room and slammed the man against the wall, Stevenson pleaded with them to stop.

“He planted his feet … and then he turned to me and said, ‘Bryan, don’t worry about this. You just come back,’” Stevenson said. “And then he did [something] that I’ll never forget. He closed his eyes, he threw his head back, and he started to sing.”

The man’s voice sung a hymn:

“I’m pressing on the upward way, new heights I’m gaining every day … Lord plant my feet on higher ground.”

“You could hear the chains clanging as they pushed this man down the hallway, but you could also hear him singing about higher ground,” Stevenson said.

“I believe that in jails and prisons across the state of Louisiana, people are still singing,” Stevenson said. “ … And if we have the courage to get close enough to the poor and the marginalized and hear these songs, not only can we do something to change the justice quotient, we can do something for ourselves.”

“That was the moment that I knew I wanted to help condemned people get to higher ground,” Stevenson said. “But I also knew that my journey to higher ground was tied to his journey.”

Since then, Stevenson and the EJI have won reversals or releases for more than 140 wrongly condemned death row prisoners. But the deeper battle, he explained, is the one over truth.

“ … We’re in the midst of a really critical narrative struggle,” he said. “We deny ourselves the beauty of justice when we refuse to tell the truth.”

He argued that the legacy of slavery in America was not just in the forced labor, but in the false narrative it created — a hierarchy that labeled Black people as “less worthy, less human, less evolved.” That narrative, he said, has never been fully confronted.

To help the nation reckon with its past, Stevenson and the EJI established the Legacy Museum, the National Memorial for Peace and Justice and, most recently, the Freedom Monument Sculpture Park in Montgomery, Alabama.

The new site, built on the banks of the Alabama River where tens of thousands of enslaved people were trafficked, features the names of 720,000 formerly enslaved individuals who, after the Civil War, chose family names for the first time.

“For the first time, the descendants of enslaved people in this country can come to a place in America where you can find your family name,” Stevenson said.

“What I’ve learned doing this work is that enslaved people weren’t just traumatized and … mistreated. Enslaved people were remarkable in their capacity to love in the midst of agony,” he said. “We need to honor this remarkable community who chose citizenship after the Civil War … despite all of that abuse and mistreatment.”

Even with decades of advocacy behind him, Stevenson remains grounded in humility. “If I’ve helped anybody during my legal career, if my career has meant anything to any of my clients, it’s not because I’m smart or hardworking,” he said. “It’s because I got close enough to a condemned man to hear his song.”

And for those privileged enough to hear Stevenson speak in New Orleans, his message was clear: The song of fighting for equal justice continues.