Professor presents new approach to high blood pressure standards

November 18, 2015

Tulane’s own Dr. Paul Whelton has proved that everything we know about lowering systolic blood pressure in high-risk patients is wrong.

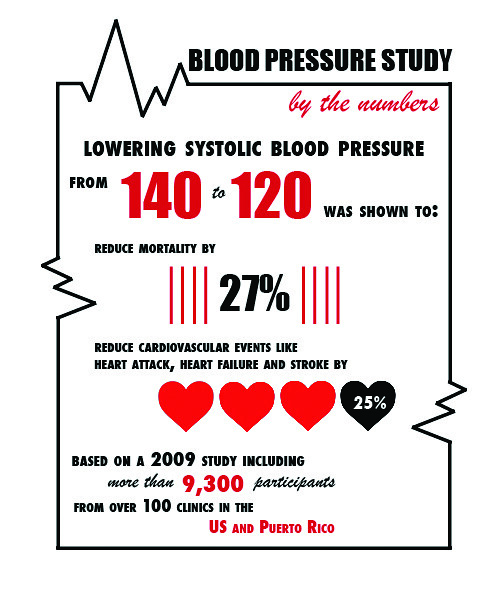

Traditionally, doctors have recommended that patients with high blood pressure only need to lower their systolic blood pressure to 140. In a study Whelton led under the National Institutes of Health released on Nov. 9 to the New England Journal of Medicine’s website, he proved that lowering systolic blood pressure to 120 is more effective and will reduce rates of mortality and cardiovascular diseases.

“The group that was randomized to the lower goal did considerably better,” Whelton said. “In fact, they did so much better that the trial was stopped early.”

The Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial, known as SPRINT, answered the question of how low to take blood pressure when treating patients with hypertension. It was a randomized trial in which participating hypertension patients were either assigned to the currently used blood pressure goal of 140 or a lower goal of 120. The patients were then followed over time to monitor the effects of each group.

While these trials typically last about five years, the SPRINT trial was ended after about three years due to the dramatic nature of its results. There was a 27-percent reduction in mortality and a 25-percent reduction in cardiovascular events such as heart attack and stroke amongst the group with the lower blood pressure goal.

After the release of the results of this study on Nov. 9, Whelton made national headlines in the New England Journal of Medicine. Whelton presented the results of the trial to the American Heart Association. These results may change the way high-risk patients are treated.

“[Whelton] was the guy in charge of putting all this together … ,” said Dr. Dan Jones, professor of medicine and interim chair of the Department of Medicine at the University of Mississippi Medical Center. “He is the main honcho — he’s the big deal.”

According to Whelton, the significance of these results is most applicable to high-risk patients with hypertension who are older and have an increased risk for cardiovascular diseases. Whelton also noted that the findings of this study were homogenous among the different subgroups of the study. The findings were constant regardless of varying race or gender. All participants were over the age of 50.

That does not mean that blood pressure monitoring is only for older adults and the elderly. According to Whelton, hypertension is less common in young people but it is more of a concern when hypertension is present in a young person. His colleague Jones says certain factors such as family history, sodium intake and body mass index can increase chances of developing hypertension. Jones recommends young people, such as college students, getting their blood pressure checked every two to three years.

“We are still collecting information,” Whelton said. “We’re very interested in what impact the lower blood pressure might have on cognitive impairments, dementia, brain function.”

Senior Staff Reporter Akash Desai contributed to this report.

Leave a Comment