Africana fashion: serving looks, untold history and resistance

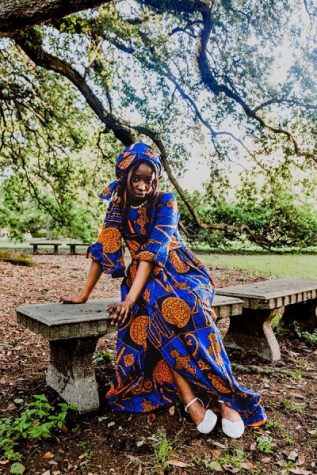

“My personal motto is: ‘You look good, you feel good, you do good,’” senior Abi Mbaye said. “Fashion is a way for me to empower myself. It is a way for me to take up space and be seen in the way that I want to be seen — especially when you exist in a space where you are invisible and hypervisible at the same time.”

Fashion does not only dominate our cultures. It dominates our politics, economy and just about any aspect of life we may not yet realize. In fact, the global clothing and textile industry had a value of about $2.6 trillion in 2010. This number is only expected to span further, as 55% of apparel and footwear sales are projected to occur in non-Western markets for 2025.

Until recently, Western markets dominated the fashion industry. Consequently, the visual and cultural processes of fashion are dominated by Western tastes and trends. What does that look like for non-Western cultures?

“Africa oftentimes in the Western cultural context emerges as a problem … fashion is seen as as a frivolous thing, it’s seen as something that’s a sight for leisure … in the Western imagination, those two things don’t come together,” Tulane Africana Studies professor Imma Zetoile said.

Fashion in sub-Saharan Africa dates back thousands of years. Since most of Africa has a warm climate, many African civilizations tended to wear minimal clothing, if any at all. Men and women wore a loin cloth around their waist, and women in particular wore wraps to cover their breasts.

This minimalism starkly contrasted European fashion, in which women were expected to not show skin except for the face at all, and men were expected to complement their athletic bodies through tight clothing. The Western perception of fashion was evidently not comparable to African fashion.

African fashion changed over time with new, innovative clothing. The barkcloth, a versatile textile made from the bark of the mutuba tree in Uganda, makes for an environmentally-sustainable and accessible garment that is more popular today in Africa and other parts of the world. The barkcloth is so important to Ugandan culture and so innovative in fashion that UNESCO recognizes the barkcloth as a Masterpiece of Intangible Heritage.

Other examples of how African fashion impacted the status quo are furs and skins. Furs and skins originally had the purpose of being a significant symbol and often displayed tribe allegiance and personal totems. They had a greater spiritual significance than just looking nice on people, and in some parts of Africa this remains unchanged and should be respected. The unethical overuse of furs and skins by some organizations are unfortunately impacting the conservation status of some animals in Africa. The population of the Grevy’s zebra, for example, declined by 54% in the past three decades due to poaching for its skin.

Traditional African prints often involve colorful patterns with cotton fabrics and distinguish one ethnic group from another. They remain popular in many African countries today, and for some cultures, the use of certain prints is becoming part of a bigger movement.

“Fashion is very important in my heritage,” Mbaye said. “I am Senegalese from the Wolof people, and Wolof women are known to be very fashionable, especially the women who always look very regal and dress very colorfully and flamboyantly. There is a word called sansè which Senegalese people use to describe someone who is beautifully dressed. The idea of sansè is very much part of the culture.”

“One recent sort of performance of black queer fashion has been the use of the headwrap in South Africa … it has emerged in the last couple years in youth popular student culture and has been a way of protesting sort of the colonization of the university space and as a way of giving honor and respect to the women who are often inhabiting university space at the margins,” Dr. Zetoile said. “The women who clean, the women who cook, the women who take care of all those kinds of business at the university spaces but often times are not respected and are not given a living wage … the idea that I have to assimilate into white culture to be an academic, to be successful, to be a CEO, all these things is what these young women, many of them queer, were not invested in.”

As a result of the enslavement and diaspora of sub-Saharan African people, the due influence of traditional African fashion is seen around the world. The dashiki, originating from West Africa, is particularly popular among the African American community here in the U.S. The dashiki exemplifies once again how fashion equals resistance, as the dashiki was popularized by the Civil Rights Movement and the Black Panthers in the 1960s and 1970s as a rejection of Western cultural norms and a symbol of Black pride. Because of this cultural and political significance, the appropriation of the dashiki by non-Black people is heavily frowned upon.

“In the last 50 years or so fashion has become a venue and a text in a way Black people can re-claim themselves as agents, as empowered and as beautiful, and for black women especially … when beauty has always been tied to white femininity, fashion becomes a really important sight for our articulation of our own beauty, our redefinition of a beauty standard that has at often times been used against us,” Dr. Zetoile said.

The U.S. isn’t the only country to be impacted by this new movement. In the state of Bahía in Brazil, Afro-Brazilian designers such as Renato Carneiro are becoming staple names in the country’s fashion industry. Carneiro’s store in the city of Salvador takes inspiration from the clothing of the syncretic religion of candomblé, which blends traditional African beliefs with Brazilian practices.

“I feel like some of my biggest role models use fashion as a form of resistance,” Mbaye said. “Winnie Madikizela Mandela, for example, who was critical in the anti-apartheid movement, used fashion to resist the colonial patriarchy by wearing her traditional clothes and accessories during the height of apartheid and always because she knows the political implications that it had and still has today. I think that is powerful, I admire that and I want to embody the spirit of Madikizela Mandela whenever I can.”

As for the future of African fashion, a time to reclaim its spot as a major global influence is already underway. Fashion publication “Fashion Africa”, founded in 2011, helped popularize the new wave of African fashion and design. The content also rose awareness of ethical fashion and provided resources to lead fashion companies into sourcing from local businesses. African designers Lisa Folawiyo, whose dresses have been worn by celebrities like Solange Knowles and Lupita Nyong’O and Aboubakar Fofana are becoming big names in the industry.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Tulane University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Fatima Djobo • Jun 15, 2019 at 11:00 pm

I need the loincloth of new collection