Tulane purchases 300,000 SAT-takers’ names as acceptance rate falls to all-time low

After taking the SAT in his junior year of high school, Tan, a Vietnamese immigrant and Washington, D.C. resident, started receiving mail from Tulane.

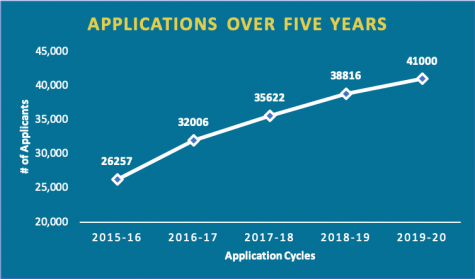

Tan visited campus, reached out to the Office of Financial Aid and sent a professor his application essay to read over. Then, along with the more than 41,000 other applicants to Tulane’s Class of 2024, Tan submitted his application and hoped he would be accepted.

To his surprise, Tan was not among the approximately 5,300 students admitted. Like thousands of other students, Tan was sought out by Tulane, receiving emails and letters encouraging him to apply.

The messages told him he would be given “priority consideration” and would not have to pay an application fee even though Tulane dropped its application fee in 2006.

“Honestly, I mostly [applied to Tulane] because of the waived application fee,” Tan said. “It was kind of far away from my home, so if they had not sent me emails, I probably would not have applied.”

Tan’s name and student profile was most likely one of 300,000 that Tulane purchased from the College Board according to a Wall Street Journal report. By buying the names of SAT-takers, Tulane is able to encourage more students to apply, helping achieve its all-time highest selectivity rating of 13%.

Higher selectivity corresponds with higher rankings for universities, encouraging schools to focus on their numbers games and reputations for exclusivity.

Tulane calls the College Board transaction a common practice among university admissions departments, used to reach students across the world. Experts say the practice is questionable, however, and that Tulane is known for aggressively courting students, whether or not they have a prospect of being accepted.

“We have students that we work with every year — dozens of students — who have no chance of getting into Tulane who will receive a mailing from Tulane,” Andrew Belasco, CEO and President of college preparation company College Transitions, said.

Following the widely read WSJ investigation, students and families across the country posed questions about how their data is being used and how universities like Tulane interact with the little-known but far-reaching College Board service.

What is the Student Search Service?

When students take the PSAT, SAT or an AP test, all offered by the College Board, they fill out a questionnaire that includes an opt-in question for the Student Search Service. By selecting yes on the SAT, students agree to share their name, birthdate, mailing address, email address, GPA, gender, ethnicity and more data.

According to the College Board, about 1,900 colleges and scholarship programs use the service which began in 1972. There are about 5,300 colleges and universities in the U.S.

“Once you opt in to Student Search, you’ll start getting information that can help you find a college that’s a good fit for you,” the College Board’s website reads. “You may get emails, postal mail, or both. All of this information helps you get a better understanding of your opportunities, so you can find the right college.”

Students can opt out by filling out a form online.

To my students: this is a must read! Do not let the College Board sell your information just to help universities seem more competitive and add to your college application stress. Opt out of their student search service. #OptOut https://t.co/fbasL0dEFI

— Lisa Thyer (she/her) (@ThyerLisa) November 8, 2019

Satyajit Dattagupta, Tulane’s vice president of Enrollment Management and dean of admission, calls it a common practice among colleges and universities.

“One of the reasons we do this is Tulane travels to a lot of cities and a lot of countries, but there are a lot of cities we don’t go to, and for students in those regions, how would they know about a place like Tulane if we don’t tell them?” Dattagupta said. “In remote areas, rural areas, countries that we don’t travel to, it’s very important for me, I believe, to reach out to those students.”

Dattagupta says that purchasing SAT-takers’ names helps to strengthen Tulane’s applicant pool and is a traditional way for admissions departments to engage with prospective students.

Criticisms of the practice

Not everybody supports Tulane’s yearly College Board data purchase.

Junior Didi Ikeji is an intern in the Office of Admission and a vice president of the Tulane tour guide program, Green Wave Ambassadors. Ikeji said despite her involvement in the admission office, she had never heard of Tulane’s involvement in the program.

“I am trying to think how it would have been different if we had just known,” Ikeji said. “Would people actively have cared as much if we knew this was happening? Or is it just because it’s just some other college scandal that we didn’t know about?”

Belasco, whose company serves hundreds of prospective students every year, calls the practice questionable and problematic. He has noticed that the caliber of students whom Tulane admits has not differed much year to year even if the rising selectivity might tell a different story to prospective families.

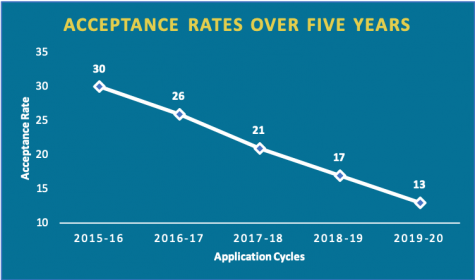

“There may be a slight uptick in selectivity, but really why those acceptance rates are probably lowering, if we could guess based upon what we could see with marketing, is that there are just more students that are applying that don’t really have a shot at getting in,” Belasco said.

Adrian Moreira, a freshman at Princeton who was waitlisted from Tulane, also finds the practice ethically questionable. He said that the way Tulane reaches out to applicants and informs them of their free, essayless application equates to a marketing scheme.

“That’s the way they increase their applications so they can lower their acceptance rates and be more prestigious ‘cause it’s a numbers game with rankings,” Moreira said.

For as little as 47 cents per student or $7,710 for a yearly subscription, schools like Tulane purchase data from the College Board, a transaction in which both parties benefit.

“There are so many other barriers for students to even take these tests that it’s even more unfair,” Ikeji said. “On top of that, the College Board is profiting off of us being forced to take these tests.”

Breaking down the data

While Dattagupta said that Tulane does not purchase SAT data in an effort to boost selectivity, Tulane’s acceptance rate has plummeted to an all-time low.

In a press release touting the Class of 2023 as Tulane’s “most selective yet,” the university announced its 13% acceptance rate for the last application season.

Five years ago, the acceptance rate was more than double that at 30% with about 26,000 applications according to Tulane admission data. Nearly 15,000 more students applied in last year’s cycle.

“It’s no secret Tulane has done an effective job of overhauling their acceptance rate over the last few years,” Belasco said. “Part of that might be the result of some of these aggressive marketing techniques — you’re increasing the number of applicants, you’re raising that denominator and that just naturally will lower the acceptance rate, especially for the students that are applying with no chance of getting in.”

Dattagupta said that Tulane Admission is not intentionally pursuing a lower selectivity rate, however.

“I come from a low-income international family, I came to this country with literally nothing,” Dattagupta said. “My goal is to match the right students with the right institutions, and I am lucky to work for an institution that is very popular right now, it just is.”

“It’s not one of the things we aspire to do, it’s just we aspire to be the best institution that we can be for the best kind of student.”

“The nature of the game”

The way that Tulane markets itself has also come under fire from current students and rejected applicants. Some say they feel that Tulane misleads students in the way it uses data to reach out to prospective applicants.

Many students receive messages from Tulane informing them of their “priority consideration” which includes a free application, even though no applicants pay an application fee. Tulane has also succeeded in increasing its applicant pool by making its essay optional.

“It’s sort of weird ethically to invite these kids to apply, knowing you’re going to reject them,” Morreira said. “The people who check it off on the Common [Application] and then don’t send in their supplement, usually they’re going to get rejected.”

Though college admissions departments are under heightened scrutiny, especially following a national scandal that helped privileged students exploit the system for undeserved acceptances, the methods of marketing and data purchasing are unlikely to change in the future.

“The nature of the game is that when people apply, X percent of them won’t get in — that doesn’t mean that we are misleading them,” Dattagupta said. “But that’s just how the college application process works.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of Tulane University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

k. martell • Mar 28, 2021 at 8:18 am

This story is very interesting. Thank you for reporting on these issues.

One high tier school just offered our teen a freshman study abroad, all year, or internship, freshman, 3/4 time of semester one or two. (But his SATs are above the mid range, over 1400, and GPA is 4.1)

Marketing costs must be a huge part of their budgets ~ After scoring a 1360 in 10th grade, age 15, SAT, we saved most of the mailers, brochures, etc. and put them on a scale == 26 pounds! What a waste!

And the spam emails were incredible.

We are now waiting to hear from Tulane ~ not because of any specific marketing ploys…just word of mouth recommendations.

His pediatrician told us her daughter loves it there, and she turned down an offer from UVA!

Trot pony • Aug 27, 2020 at 8:32 pm

It’s true that Tulane isn’t the only school who does this. I still remember getting invitations from the University of Chicago senior year of high school. I definitely didn’t have the caliber to be admitted into that school, so I was questioning why. Now I that I know after reading this article.

Flynn Vertz • Dec 16, 2019 at 2:57 pm

While artificially increasing acceptance rates though marketing schemes is one strategy universities use, it is for sure not the only one.

Another tactic used by Tulane is their Spring Scholar program. Every year around 100 students or so are accepted to start in the spring semester of their freshmen year. Spring acceptance is yet another way for Tulane and other selective universities to game ranking formulas.

“Admitted students with so-so high school grades and SAT scores were encouraged to study abroad for their first semester in a newly created program because students who start in the spring don’t count for US News purposes.”

https://www.vox.com/2014/9/5/6106807/college-rankings-us-news-boston-clemson-problems

By doing this, the university can both accept students who otherwise would have hurt their freshman class profile, while allowing them to attend the university. While this, in turn, benefits the student who may otherwise have been denied, there are moral questions to be asked. Is it right for universities to put a student’s life on hold, or to pressure a student into an expensive study abroad programs, or even possibly delay their graduation, all to cultivate a better class profile on paper?

Last note: The article I am citing this information from an article that quotes an old US News ranking formula, and thus this may no longer be true at the time of the comment.