Racial healthcare disparities go unaddressed in vaccine rollout

March 31, 2021

Over the course of the past year, COVID-19 has permanently altered the lives of people across the globe. Within the U.S., however, some groups may have been affected more than others, and with the vaccine rollout underway, it is only logical for those groups to receive immunization before less-impacted groups.

The vaccine priority groups have been shown through the stages of the rollout, with healthcare workers, the elderly, people with underlying health conditions and others being among the first to become fully vaccinated as they were most at-risk for exposure or serious illness. These priority groups fail to include another factor which has made COVID-19 more harmful and fatal for some: race and ethnicity.

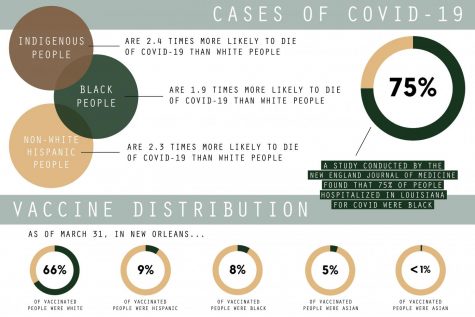

The pandemic has exacerbated the differences in resources, opportunities and healthcare between different communities of people, with historically discriminated and marginalized communities faring worse. In particular, non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Native, non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic or Latino persons have shown higher rates of cases, hospitalizations and deaths as compared to their non-Hispanic white counterparts. Data for non-Hispanic Asian persons has proven to be inadequate for proper identification of the impact on this vulnerable population. It is, however, clear that Asian American and Pacific Islanders have been targeted more frequently by xenophobia throughout the pandemic, adding to the mental strain the pandemic has already created.

By March 15, 2021, white people made up two-thirds of the people vaccinated. The Black, Indigenous, Hispanic and AAPI populations had not received vaccinations proportionally to their morbidity and mortality rates, much less their age-adjusted population. Here exists a clear disparity in health equity between white people and any other community of color.

These health inequities exist from systemic racism and prejudice against people of color. The trauma of racism and bigotry can lead to underlying health problems such as obesity and diabetes, which increase the morbidity and mortality risk of COVID-19. Likewise, the redlining of cities which occurred during the 1930s prevented many minority and low-income families living within the “undesirable” neighborhoods from building any generational wealth, making healthcare difficult to attain. These factors have proven detrimental during the pandemic as lack of healthcare leads to delays in obtaining necessary treatment for COVID-19. Minority groups were also overrepresented in essential work environments, making them more vulnerable to the spread of the virus.

The distribution of the vaccines for COVID-19 did not adequately address the greater obstacles and risks which many marginalized groups faced. These groups needed priority alongside the other groups of similar risk for exposure, hospitalization and death. Reparations need to be made through providing resources and healthcare such that if another pandemic were to happen, marginalized communities would not face greater harm than others.

Leave a Comment