OPINION | New Orleans, not New Orleanians, needs resiliency

February 23, 2022

On Sat. Feb. 12, Krewe du Vieux rolled — ambled? — for the first time in two years, with typical satire and neon aplomb.

Even without New Orleans health director Dr. Jennifer Avegno, Krewe du Vieux’s queen, riding alongside them, the presence of New Orleans’ government establishment was keenly felt.

The vaccine mandate, the rebranding of the Caesars Superdome and Mayor Latoya Cantrell’s controversies were all subject to the Krewe du Vieux mockery — a time honored tradition abated only by COVID-19.

One float in particular remarked that in New Orleans, a city often faced with chaos, controversy and catastrophe, it is not easy to be resilient.

Evidently, it is not.

Rampant crime, mountains of trash, power outages and hurricanes make it quite difficult, in fact, to be resilient.

New Orleanians have been subjected to the “resiliency narrative” — the idea that natural disasters and struggles cannot beat down the spirits of New Orleans’ residents — almost continually for the better part of two decades now.

There was Hurricane Katrina, of course, which even spawned academic discourse about Krewe du Vieux and the “resilient city.”

Who could forget the national — and foolish — castigation that the New Orleans community were subjected to over COVID-19 and Mardi Gras, before evidence emerged suggesting the coronavirus was in our community long before Fat Tuesday, 2020?

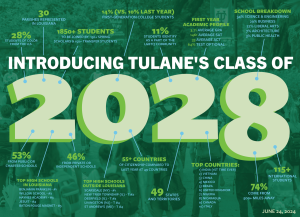

After Hurricane Ida, demands for resilience continued as Tulane University expected that faculty — evacuated across the country, with their children and their pets — teach remotely and virtually, faced with uncertainty over the state of their homes or amidst arguments with insurance adjusters.

Throughout it all, our appointed and elected leaders insisted that New Orleanians are a resilient bunch.

“I am proud of our residents, volunteers, and workers for staying resilient while our city recovers from Hurricane Ida,” Cantrell said on Twitter.

After Hurricane Zeta in 2020, Tulane President Mike Fitts told the community that they had “weathered Zeta with uncommon resilience and good cheer.”

Ramsey Green, New Orleans’ chief resilience officer, said that even after Hurricane Ida, New Orleans “is so far ahead of [other cities in] building infrastructure to combat and prepare our city for climate change.”

Following each catastrophe, New Orleanians are praised for their ability to band together and recover quickly from events that harm their families, homes and livelihoods. At this point, it seems as if resiliency is almost expected from city inhabitants. More than just that, resiliency seems to have become the only solution that New Orleanians have to the numerous challenges we face.

Now admittedly, as a transplant at best and a carpet-bagging Northerner Tulane-undergraduate gentrifier at worst, my authority to speak on this subject is limited.

But when the singular source of power for Louisiana’s largest city collapses into the Mississippi River, my roots don’t have to be particularly deep to know that somebody burnt the roux.

The failure of New Orleans’ black start ability – designed to stimulate power flow in catastrophic failure situations just like Ida’s – is not necessarily Green’s fault. But it would seem to contradict his contention that New Orleans is lightyears ahead of other American cities when it comes to infrastructure resiliency.

Of course, hurricanes are ungodly, hugely powerful forces of which few structures can resist.

But, as if anyone needs reminding, Louisiana has two seasons that not all other states in America do. One, of course, is Mardi Gras. The other is “hurricane season.”

To put it bluntly — not a single person is surprised when hurricanes strike Orleans Parish.

It would not be an overreach to say that New Orleanians are bone tired — of boil water advisories, of a brief rainstorm bringing flooded streets, of running out of their stockpiled food, of getting carjacked on their way to get that food.

To add fuel to the fire, officials and leaders constantly calling New Orleanians “resilient” seems more like an effort to redirect attention away from the real structural issues endemic to New Orleans’ infrastructure and onto the citizens who live and struggle with their impact.

It is not fair to lay this solely at the feet of the current administration. Academics have begun whole careers examining the historical and deep structural issues — literally and figuratively — with our infrastructure.

There are some plainly obvious solutions to our infrastructure problems: burying power lines, modernizing our antiquated sewerage system, wresting energy control from a legal monopoly and maintaining our levees. Doubtlessly, Green, Entergy and the engineers would find ways to explain these solutions as unfeasible.

To quote Ashley Morris’ inimitable piece after Katrina — a man-made disaster — laid waste to much of New Orleans:

“You said ‘we will do what it takes.’ Then do it.”

Leave a Comment