Clearing up Tulane’s protocols on protests

October 12, 2022

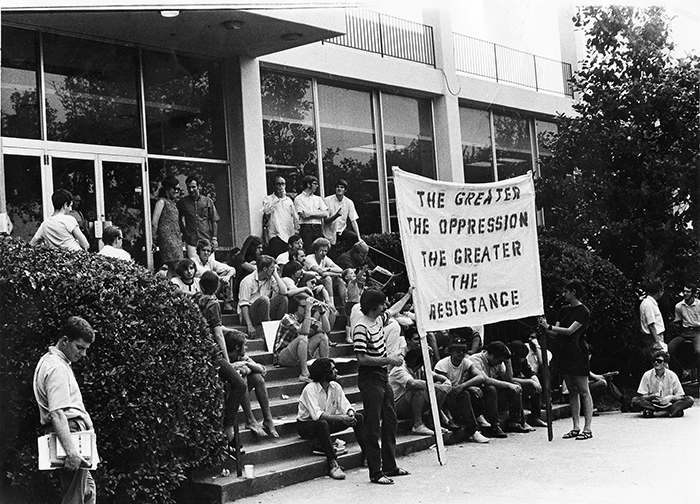

Tulane University students rallied last year to voice concerns over the university’s role in sustainability, abortion rights, gay rights and sexual assault on campus. Across the country, debates rage over free speech on campuses as political stances become more divisive.

But an anti-abortion and anti-gay protest staged by a small, non-Tulane affiliated Christian group on the intersection of Freret Street and McAlister Place on Sept. 2 left some students confused about what protests are allowed on campus — and why.

According to Laura Osteen, assistant vice president for campus life, no Tulane protest request has ever been denied. As long as protests are done by Tulane affiliates and do not become disruptive, the Division of Student Affairs encourages them, Osteen said.

The Sept. 2 protest was staged by non-Tulane affiliates but was allowed because it was held on New Orleans property, not Tulane property. Heather Seaman, director of the Lavin-Bernick Center for University Life, said the group was “sophisticated enough to know… they were on a city sidewalk and not coming onto campus. That is challenging because it feels like it is on campus, and that distinction is not extraordinarily visible.”

Osteen said she believed the protest was harmful to students and called the group’s messages “violent.” The Division of Student Affairs is looking into ways to handle a protest like that if it were to occur again to minimize harmful impacts to students and staff.

But if the same type of protest was held by Tulane affiliates, Osteen said, the school could become more involved.

“That’s where we get into the distinction between hate speech and free speech,” Osteen said. “That would be something we would most definitely examine closely.”

Osteen said the Tulane protest policy revolves around three things: “time, place and manner.” As long as protests have a voice without disrupting university life, Osteen and Seaman work to support them with the full resources of their office.

“Judgment decisions are not based on content,” Seaman said. “The goal is to help amplify the voice or concern of what the students are wanting to express, not making content decisions for them.”

Students have complained in the past about what types of protests are allowed on campus. At an on campus anti-abortion demonstration last April, several counterprotesters raised concerns about why Tulane allowed the protest on campus.

Osteen and Seaman said they are trying to find ways to educate more students about Tulane’s jurisdiction over protests.

“We’re cognizant that’s always not going to solve everyones’ concerns,” Seaman said. “But I think it’s going to put resources quickly out there and [make them] accessible for people to just understand, in the moment, what is available.”

Even when protests do not go through the correct formal registration process, such as counterprotests, Campus Life works to support them with the “goal to ensure people’s safety” and “people’s ability to communicate their message,” Seaman said.

Osteen said she is constantly trying to answer the question, “How do we encourage more [students to] feel like they are empowered in their own ability to shine in a different light?” She said she believes her responsibility is to honor the ideals of “curiosity and [the] examination of ideas” that uphold university life.

Osteen and Seaman said that although Tulane is a private institution, it still has a responsibility to uphold the First Amendment.

“That is what we’re here to do,” Seaman said, “to challenge ourselves, to examine why we believe what we believe, and I think demonstrations are a way for students to express that voice.”

Leave a Comment