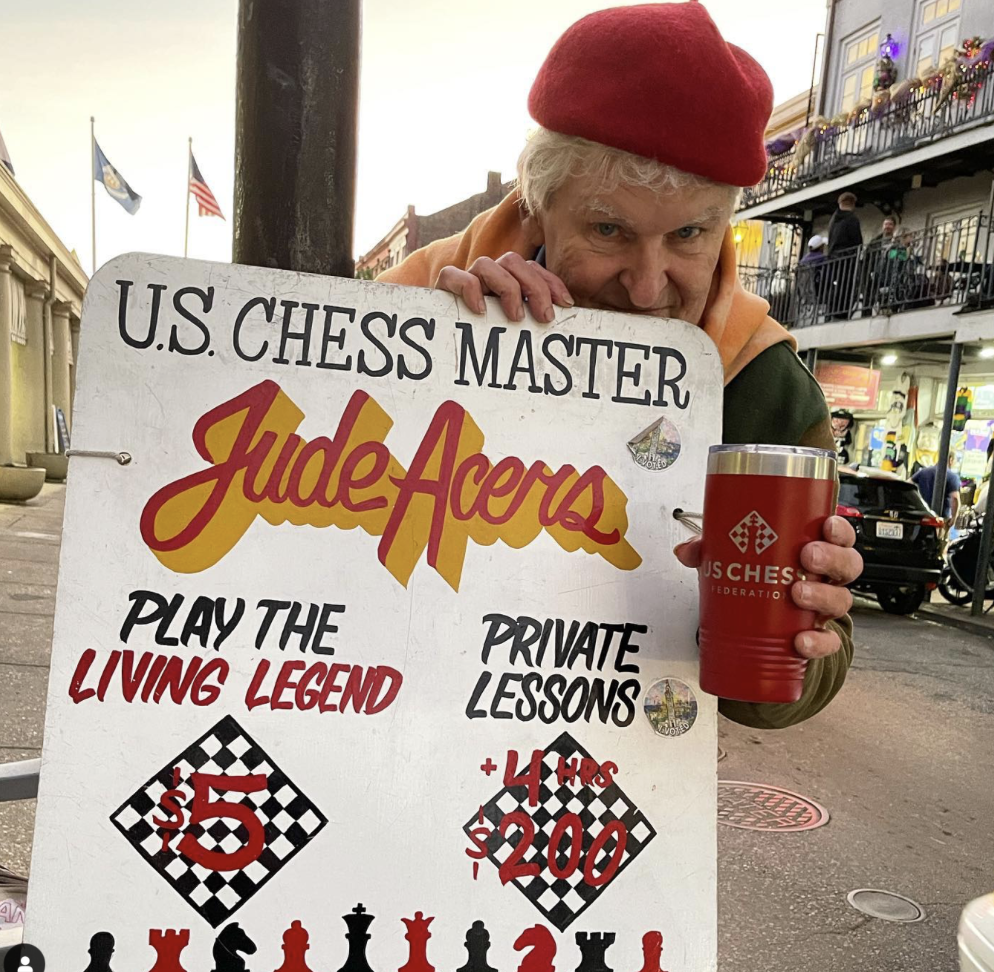

An elderly man sits cross-legged outside a French Quarter cafe. His face is hidden behind the Sunday news, but a conspicuous beret pokes over the edge of the paper. He has a chaotic stack of more reading materials, two chessboards and a sign.

It reads, “Play the Living Legend.”

That legend is Jude Acers, and for $5, players from all skill sets, backgrounds and levels of intoxication can challenge the 79-year-old chess master. His patented bright red beret has been a fixture and delight to anyone who’s ventured down Decatur Street for the past 42 years.

“Are you ‘The Man in the Red Beret’?” I asked, before handing him the cash one Sunday evening.

I had been primed by a friend on what might happen. Will Carnahan, a Tulane University senior, still remembers his freshman year experience with Acers.

“Jude from the start was nothing short of a character,” he said, before recalling his 40-minute lecture by Acers about the rankings system in chess and the progression he’s seen in New Orleans over the years.

I, too, was lectured. After admitting I was a novice, Acers turned every one of my blunders into a lesson.

“No matter what, never, ever resign,” he said when I began to give up, “then you won’t learn from your mistakes.”

I then asked to interview him for The Hullabaloo. He said I had great instincts, which at least in this case proved to be true.

___

A voracious reader prone to political and philosophical ramblings, interviewing Acers is an intellectual rollercoaster where one must completely cede control and simply enjoy the ride.

Topics ranged from Taylor Swift to the Internal Revenue Service, from the importance of women in his life to the secrets of longevity.

“Go to wild parties, wild music, play the radio a great deal,” he said. But, “I do not drink, I do not smoke. I do not do dope. I have not been to a doctor for anything in 30 years.”

He stays up all night listening to music and studying chess, sleeping through the morning before setting up his table in the afternoon. It’s not uncommon to receive dozens of emails at 3 a.m. from Acers, oftentimes with 20 other strangers from around the country cc’d in.

Water and heaping doses of coffee have been his fountain of youth, he says. Later in life, he advises adding something else.

“When you’re 45 to 50 years old, I will add 30 years to your life … take resveratrol,” he said. “It’s 1,500 glasses of red wine in a pill without the alcohol … It keeps your cells young.”

Acers lives alone in a small apartment in the Quarter. He leads a spartan lifestyle, with no driver’s license and seemingly no hobbies outside reading and chess.

But he relishes its simplicity, aided by what The Times-Picayune writer Doug McCash describes as “a self-aggrandizing character in the mode of Muhammad Ali.”

“I’m truly great,” Acers said, “I live like a millionaire. I’m world famous … I have enough money in the bank to live. I have enough food.”

___

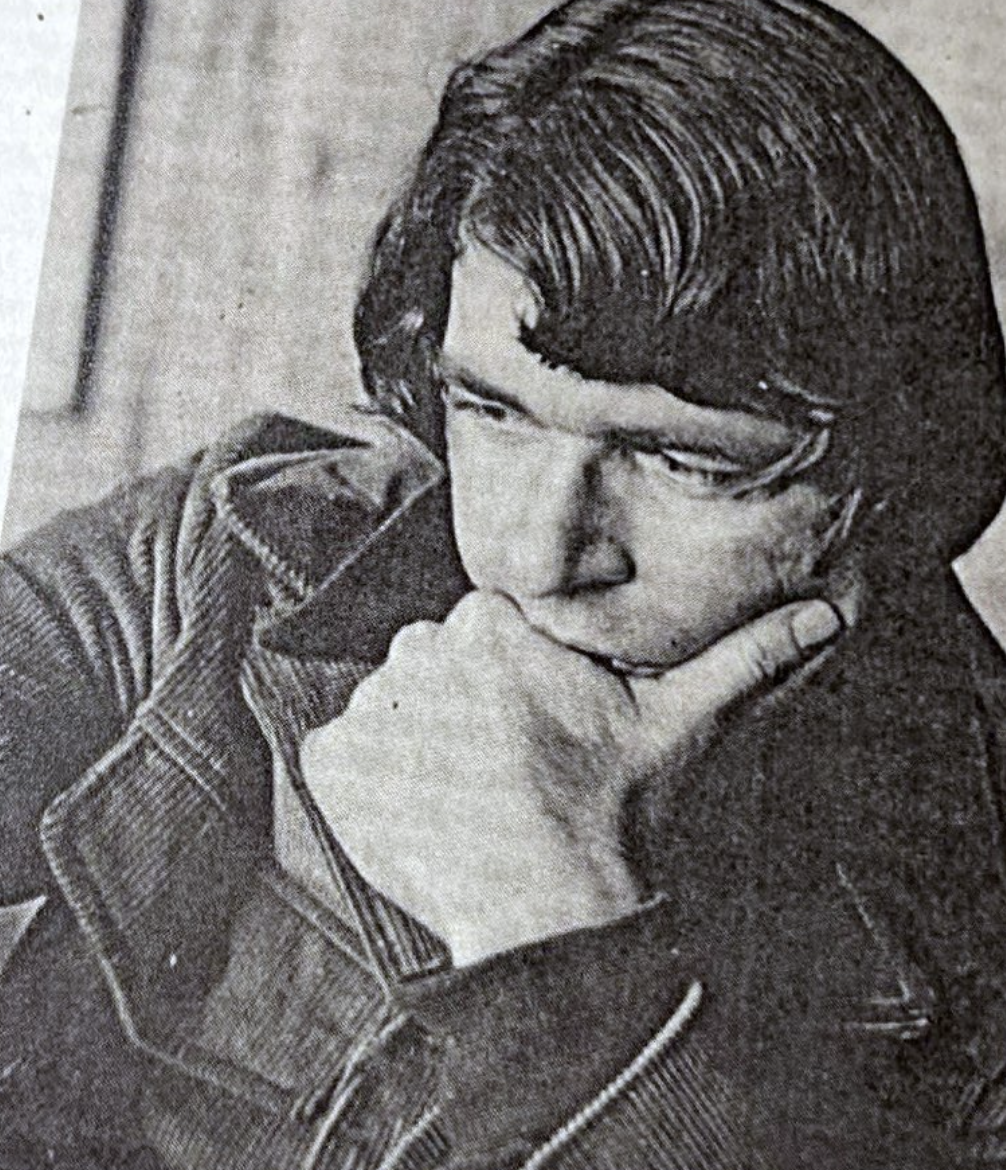

If the character arcs of Sal Paradise and Beth Harmon had a baby, it would be the life of Acers. Though he did not give much of his background in the interview, it can all be found in his book, “The Road.” He was born on April 6, 1944 in Long Beach, California, before bouncing around to Hawaii and North Carolina. His mother, a drug addict, died in a plane crash on the way to an asylum when he was three. At age five, he discovered chess in an orphanage, waiting for his father to return from combat as a Marine.

When his father came back, he moved the family to New Orleans to pursue law. But Acers’s early childhood was plagued with turmoil and neglect, fueled by his father’s alcoholism.

“His father had a penchant for shaving young Jude’s head and he once knocked Jude down in an alcoholic stupor, but generally all he offered was silence,” wrote Derek Bridges in his article “The Amazing and Slightly Irregular Jude Acers: ‘There’ll be no need for me to cry.’”

During that time, chess became a source of refuge for Acers. He wrote letters to famous chess columnists and took the hour-and-a-half bus ride from Harahan to the chess club at the Lee Circle YMCA, where local chess legend Adrian Mcauley began giving him tips.

Acers credits the game for saving his life. “Without a doubt would not have survived,” Acers said. “No way.”

At 14, Acers was sent to a mental hospital. The story goes that after seeing the father’s behavior and his living conditions, a detective arranged for Acers to fake a psychiatric evaluation so he could be responsibly cared for. He never saw his father again.

With an IQ of 167 in the ninth grade, Acers graduated as a salutatorian from Mandeville High School while living at the hospital, before receiving a scholarship to study at Louisiana State University. Once, “when I was just running for exercise, they ran after me thinking I was running away and they took me back,” he wrote, “but I, in general, realized I was being very well taken care of and if I learned to live by myself, read, I’d have a chance,” Acers wrote.

He seemed to enjoy the independence his situation granted him, never being dragged down by the confines of a family, a sentiment he holds to this day.

While at LSU, an up-and-coming chess player named Bobby Fischer stopped in Baton Rouge. The two hit it off, spending three days together shooting pool and playing chess. Though Acers never beat Fischer, he gained serious recognition for holding him to a draw in New Orleans a few days later. Fischer would go on to become the most famous chess player in American history.

In 1968, after graduating from LSU and becoming the state chess champion, Acers found his way to San Francisco at the height of the hippie movement, where he says he mixed with the likes of Janis Joplin and The Doors frontman Jim Morrison. He then hit the road on a Greyhound bus, playing exhibition games for a few hundred bucks at prisons, malls and universities. He wrote chess columns, played blindfolded and in 1973 broke the world record for playing 117 opponents at once in Portland, Oregon. In 1976, he would break that record again, playing 179 opponents in Long Island, New York.

“I did more than 1,000 chess exhibitions in 46 states and 20 countries,” he told me. In his book, he wrote, “I’m the best who ever lived at that kind of work.”

Eventually, the stresses of the road got to him. Many times Acers struggled to break even, most exhibitions paid at most around $300, forcing Acers to chess hustle to make ends meet. By 1979, the languid, genial pull of New Orleans brought him back. He eventually settled on Decatur Street outside Gazebo Cafe and hasn’t moved since.

___

Derek Bridges met Acers while working at the Loyola University library in 1999.

“He would come in late at night, and just pop around on those computers,” said Bridges.

After reading an article about Acers in Oxford American magazine, he asked to photograph him at events. They quickly became friends, eventually leading to Bridges writing about Acers’s life story. Bridges, now a videographer for Tulane’s School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine, began filming Acers in 2012 while still working at the Loyola University library.

“It made perfect sense to him. He didn’t flinch,” Bridges said. “He loves being on camera.”

Twelve years in the making, “The Man in the Red Beret” explores the inner workings of Acers’s life, his effect on the chess community and the various people whose lives he’s changed. It features perspectives from his sister, chess experts and various locals and tourists. At one point, it follows Acers as he brings Marilyn Polias, a beginner chess player, to Croatia to compete in an international chess tournament.

“He’s such a great example of the contrast [in chess],” Bridges said. “Like in Croatia when he played in a highfalutin tournament, then he gets back onto the sidewalk and there are guys dogging him.”

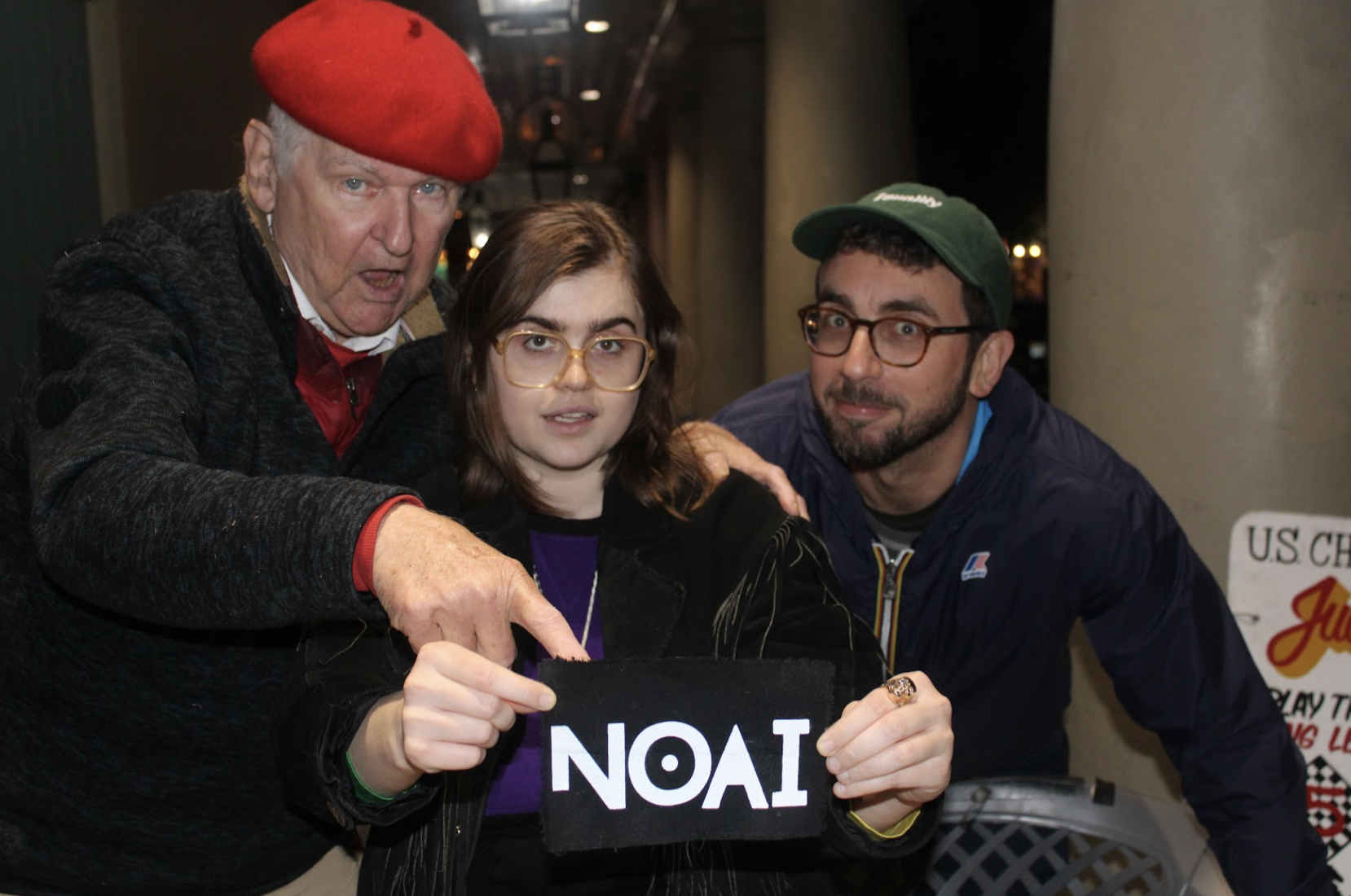

One highlight of the film is Acers’s burgeoning relationship with Baylee Badawy. Badawy, 27, is a recent graduate of Tulane School of Professional Advancement. Like Acers, she walks everywhere and has never owned a license. She also cut ties with her parents at a young age after she moved to New Orleans from Ohio at 17 to wait tables. Today, Badawy works as the marketing and communications coordinator for the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Foundation, in addition to being Acers’s pseudo-PR agent.

Unlike Acers, she is reserved and nonchalant.

“It’s not like he’s trying to keep up with me, it’s the opposite,” Badawy said in the film.

They became close after Acers started giving her chess lessons during the pandemic, a routine he insisted on maintaining before I asked questions. As usual, he was in a caffeine-induced fervor.

“What is the move that checkmates in two?” he asked Badawy eagerly. “Just take your time. This is how you develop your imagination. You force yourself to find it.”

Thankfully, she found it, and I was able to ask questions.

Their difference in dispositions makes for a wholesome duo. He likes to brag on her behalf, frequently calling her a genius and superstar. She’s more observant, with occasional bursts of laughter at his long-winded social commentaries.

“She prefers not to be noticed. Unfortunately, she knows I know everything,” said Acers. Badawy runs his Instagram, publicizes matches with celebrities like Jamie Foxx and helped him go viral on TikTok — before getting permanently banned for filming Acers waving at the World Naked Bike Ride parade.

In a way, they provide each other with a sense of familial security neither was able to experience in childhood.

“I want people to know that I love her,” said Acers.

Badawy calls Acers her biggest supporter, a common sentiment among people in his life.

“He has enormous confidence in himself,” said Bridges, “but what makes it palatable is the way he shares it with everyone else.” Thanks to him, I now consider myself the next “up-and-coming bloodhound reporter.”

Acers inspired Badawy to found a nonprofit called the Red Beret Chess Foundation. It operates out of the “Chess Cave,” a one-room, checker-walled shop on St. Phillip Street. It serves as the headquarters they use to promote chess, offering educational resources and a spot to hold exhibition matches.

Her latest project is educating others on the importance of incorporating artificial intelligence into chess. She’s working with Tulane graduate Blake Bertellucci-Booth, a tech entrepreneur and founder of the New Orleans AI symposium.

“If any Tulane students want to get to the position of a top of technology,” said Bertellucci-Booth, “they need to learn chess.”

This is something Acers has used to survive for decades in the Quarter. “Appearances mean nothing,” he said, but then admitted I initially put him off for looking like “fraternity Joe.” He stays even keel during matches, sometimes refusing to play opponents again if their behavior gets out of hand.

Meanwhile, Bridges’s film has gained critical success in the Film Festival Circuit. It recently won best documentary feature at the Abita Springs International Film Festival, and he plans to hold shows at the New Orleans Jazz Museum on April 3. The Tulane Chess Club is also working to get it shown at the Tidewater building.

Acers never reached the standing of New Orleanian Paul Morphy, acknowledged as the world’s greatest chess player during his time, but he still believes he’s made a greater contribution to the game of chess.

Though some would disagree, what’s indisputable is how Acers’s unique nature has breathed new life into the game. His mix of nonconformity and love of the people around him has made him a folk-like hero in the Quarter and has left a lasting legacy in the chess community.

“I just have to operate in a very simple way with my own work. And I don’t worry about what people think,” he said.

“He’s lived his life on his own terms,” said Bridges, “Which few of us can say we have.”

Within streets full of tourist traps, to “Play the Living Legend” is no scam — look no further than “The Man in the Red Beret.”

Correction: A previous version of this article stated Derek Bridges began filming Jude Acers in 2012, while he worked as a videographer for the Tulane School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine. The article has since been updated to reflect that in 2012, Bridges was working in the Loyola University Library.

Leave a Comment