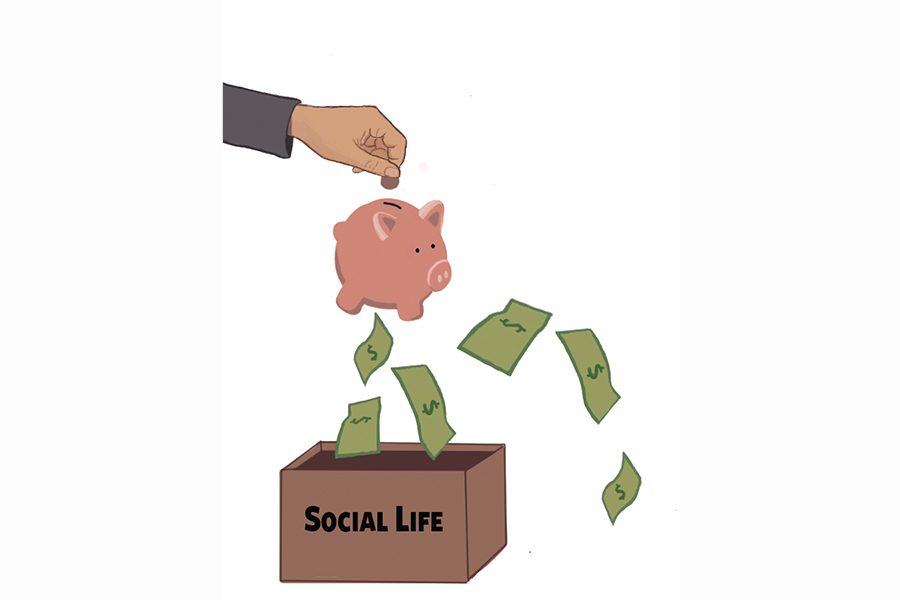

Tulane’s culture of spending magnifies wealth disparities among students

Junior Tayla Moore sits in an Uber as a feeling of dread washes over her. The music is blaring and her sorority sisters chat loudly, but Moore is not listening. She is thinking about how many hours she will have to work to make up for this one Uber ride.

“So you really got to sit there and play Tetris with your bank account to try and figure out how you’re going to get to a place,” Moore said.

She follows her friends along, not wanting to miss out on any fun experiences, but feels the money draining away as they press her to go to a party or a restaurant.

“I’m regretting this decision as I’m in the Uber, but I mean, the Uber has already charged my card, so what are you going to do?” Moore said.

Tulane students often feel pressured to spend, as they are left out from the fun if they do not participate.

“I guarantee you students will go broke. They won’t think that they’re going broke, but they will go broke before they miss out on what they perceive to be a good opportunity to have fun with their classmates,” Moore said.

Tulane’s wealth divide

According to a New York Times study from 2017, Tulane is one of 38 American colleges where students from the wealthiest one percent of the country make up a larger portion of the student body than students from the bottom 60 percent.

“At all elite institutions you can anticipate finding that kind of wealth gap, and that’s not so much the issue, because we want to be able to serve students from all sorts of different backgrounds,” Paula Booke, associate director at the Center for Academic Equity, said. “What we have to work hard as a community to ensure is that once they come here, everyone has access to that same experience that will propel them on to bigger and better things in life.”

Tulane, however, has not conducted any thorough internal analysis regarding wealth disparity.

“Tulane does not collect financial information for every student enrolled at the University,” Michael Goodman, associate vice president of university financial aid, said. “It is impossible to accurately comment on the potential family wealth of our students.”

The cost of never missing out

Sophomore Matthew Wu, who holds a job on campus, recognizes this disparity.

“At Tulane, there are so many ultra-privileged kids, where their parents seem to be bankrolling their experience,” Wu said. “If they have a credit card that they’re not paying for, they’re not going to practice fiscal responsibility.”

To be a member of Tulane’s extensive social scene, students may often feel pressured to spend money on alcohol, restaurants, Uber rides and Greek life. Sophomore Evan Doomes said he often feels the need to spend this way when he is around his friends. Doomes said he does not regret the times when he has spent more money than he planned to, and that those experiences are typically fun, but said, “it’s something that I wouldn’t have done independently.”

Sophomore Kyle McIntyre said there is always something new to see in the city, but that these opportunities create economic pressures.

“That requires Ubers, money just in general to pay for it … so activities are pricey off campus, and I feel like a lot of what this school promotes is exploring off campus,” McIntyre said.

Additionally, socializing may incur costs related to accidents. Sophomore Emily Baldridge said she was concerned with how frequently students lose money because of injuries or damaged property.

“If you roll your ankle or hurt your arm, the Health Center doesn’t have an X-ray machine, so you have to go to an urgent care [center] off campus to be treated,” Baldridge said.

Work hard to play hard: The delicate balance

Some students work jobs to earn the disposable income they said they think is needed to be a part of the social culture at Tulane. Moore acknowledged that being a resident advisor lightens the load on her parents but said she still struggles to find the money for recreational spending.

“I get paid for tabling, I get my room and board paid for being an RA, and it’s like you’re trying to find all these little ways to cut down cost, but in the end, I still run through a lot of money at school, and it’s money that I do not have to run through,” Moore said.

Adding a job to the mix of activities on campus creates an even more delicate balance for some students. Many jobs on campus have taxing hours and pay minimum wage, requiring what many see as sacrifices that are not necessarily worth it.

Isabella Smith, a desk service coordinator, said earning this expendable income has cost her more than her time. The hours she works also impact her sleep schedule.

“Working graveyard shifts is really rough, because twice a week I have to wake up in the middle of the night and work for two hours, and that throws off the rest of my day,” Smith said. “I’m not that well rested.”

Though Housing and Residence Life has since modified student “graveyard shifts,” other student jobs may require time commitments long or late enough to interfere with students’ abilities to make time to study and take part in other activities.

Even when a student decides an on-campus job is financially necessary for them, the access to jobs on campus remains limited. Moore said many of the jobs offered on campus are for work-study circumstances. She said this forces those who do not qualify for work-study to find off-campus jobs that present their own financial barriers, such as transportation.

While some students dedicate a large portion of their time to jobs that bring down their price of housing at Tulane, others are saving for more social expenses.

“I have a lot of privilege in that I’m able to work and put that money towards frat dues as opposed to my living situation and whatnot,” Wu said. “I recognize that even though I’ve had a little bit of hardship paying the dues, I still am privileged to an extent.”

Bridging the data gap

A student body hailing from a wide range of socioeconomic backgrounds has created a spending culture at Tulane that some students said has made them feel pressured to spend when they otherwise would not. In some cases, keeping up with this culture means working extra jobs and making sacrifices.

“And [the ultra-privileged] are not everyone, that’s probably the minority, but the fact that so many people are in that [top] tier of status, that means other people are also pressured to spend a similar amount of money, even if they’re not as well-off,” Wu said. “In my experience, it seems like the culture overall is spend now, worry about it later.”

Booke said she hopes the university community can start to get concrete data on the issue and what percentage of students are limited by finances for various opportunities. She also said she wants to initiate dialogue about issues the wealth gap presents.

“Having the conversation is really the first, I think best, step to creating a lasting solution that can create a more inclusive community,” Booke said.

Leave a Comment

Your donation will support the student journalists of Tulane University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Microsoft Server 2016 Support • Nov 16, 2017 at 5:02 am

Hello I wish to to share a comment here concerning you to definitely be able to inform you just how much i personally Loved this particular study. I have to elope in order to a U.S.A Day time Supper but desired to leave ya an easy comment. We preserved you Same goes with be returning subsequent function to read more of yer quality articles. Keep up the quality work.

Microsoft Server 2016 Support