Rediscovering the untold history of Colored Conventions and 19th century black activism

“America never was America to me / And yet I swear this oath — / America will be!” -Langston Hughes

Throughout the course of American history, the vitality of black activism has often hidden under the veil of larger entities that eventually became vibrant symbols of social justice reform. But before the Civil Rights Movement undermined the status quo, activists had long been meeting in large numbers to formulate ideas on achieving equal rights.

The Colored Conventions Project, an ongoing project launched from a graduate class at the University of Delaware in 2012, aims to highlight seven decades of black organizing and bring them to life through a digital platform.

On Tuesday, Gabrielle Foreman, the Ned B. Allen Professor of English and professor of History and Black American Studies at the University of Delaware, led a presentation on the project. Foreman’s talk, titled “The Long History of Civil Rights Organizing: Recovering the Forgotten Colored Conventions,” brought the atmosphere of the conventions to life as members of the audience recited different stanzas from Langston Hughes’ poem, “Let America Be America Again.” The poem emphasized the struggle, hardships and tone of black organizers and their relevance today in the discourse of black Americans.

@profgabrielle and audience members read “Let America be America Again” by Langston Hughes. pic.twitter.com/YfeVjcLPnW

— Hull Intersections (@IntersectionsTU) February 28, 2018

“This is the story of once enslaved people … who rejected the notion that they were meant to be property,” Foreman said during the event on Tuesday. “Those convention-goers made it clear that no plan or propaganda would persuade them to accept the status of second-class subordinates in the towns, in the cities, states and the country which could not have been built without their uncompensated and [back-breaking] labor.”

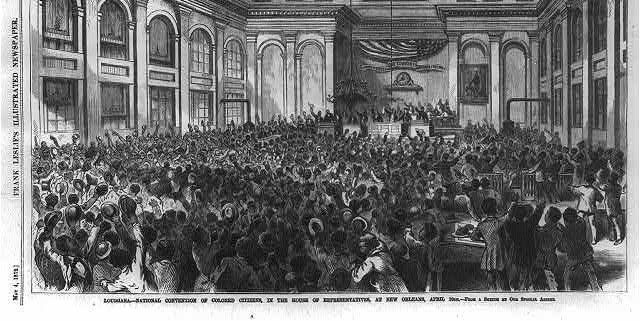

From the 1830s to the 1890s, the already free and once captive black people came together in state and national political meetings called “Colored Conventions.” They strategized on how to achieve educational, labor and legal justice at a time when black rights were constricted nationally and locally.

“When we think about early movements for racial justice, abolition and the underground railroad spring to mind,” Forman said during the event. “… It is, I dare say, feel-good, redundant history. The Colored Conventions shaped history differently, highlighting African-Americans’ relationship to each other, to the land and to the law.”

Tulane English Professor Kate Adams teaches a class called “Reconstructing America,” in which students will be joining the many researchers at the Colored Conventions Project by examining the physical and digital archives of the 1865 and 1872 Louisiana State Colored Conventions.

“It’s a class about black writers after emancipation, writing about the democracy and what has to happen to democracy for it to be genuinely a co-racial democracy,” Adams said. “We want to do more in the English department and the humanities at Tulane to think about how much humanities, cultural and racial politics intersect … and [Foreman’s] talk [was] perfect for that.”

Regarding the project, graduate student and Colored Conventions Fellow Denise Burgher’s goal is to encourage future generations to learn the past of their ancestors as they confront the present.

Local boarding house hostesses provided spaces for delegates of the convention to meet.

“It’s being able to stand in that space and affirming the older generation while inspiring younger people that there’s a history and a knowledge that exists,” Burgher said. “And so I am able to be almost a medium between the [past and the present].”

According to Foreman, the ability to unearth the disremembered histories and control the narratives of African-American people in this country as a form of generational black empowerment underscores the main objective of The Colored Conventions Project. In an era when controlling one’s own narrative is so important, the Colored Conventions Project is a key component of building that narrative.

“It is a humbling and blessed thing to be in a place to resurrect the history of the giants who are our ancestors and to make public their records … to spread the word and the history of seven decades of black organizing that reflects the very issues we struggle with today …,” Foreman said.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Tulane University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Leave a Comment