Unpacking Architecture: Vanderbilt’s accidental buildings

Courtesy of Ann Case

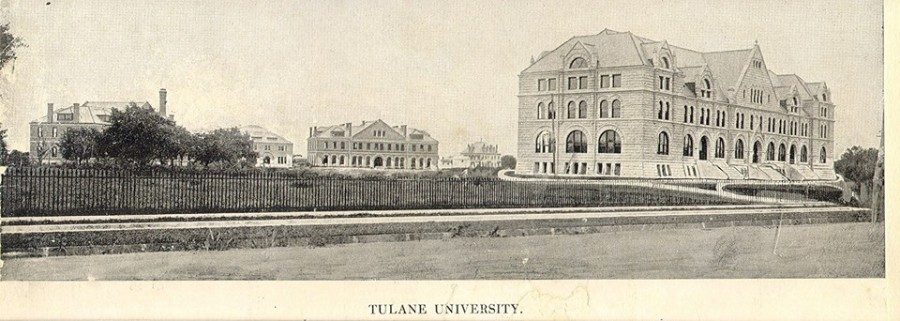

Gibson Hall, Hebert Hall and the Richardson Building were the first buildings constructed on the Gibson Quadrangle.

According to campus legend, the reason the F. Edward Hebert Hall and Richardson Building don’t match the rest of the Academic Quad is that their bricks were swapped for bricks destined for Vanderbilt University. While this story is not true, these buildings, which are some of the oldest on campus, do have their own unique quirks.

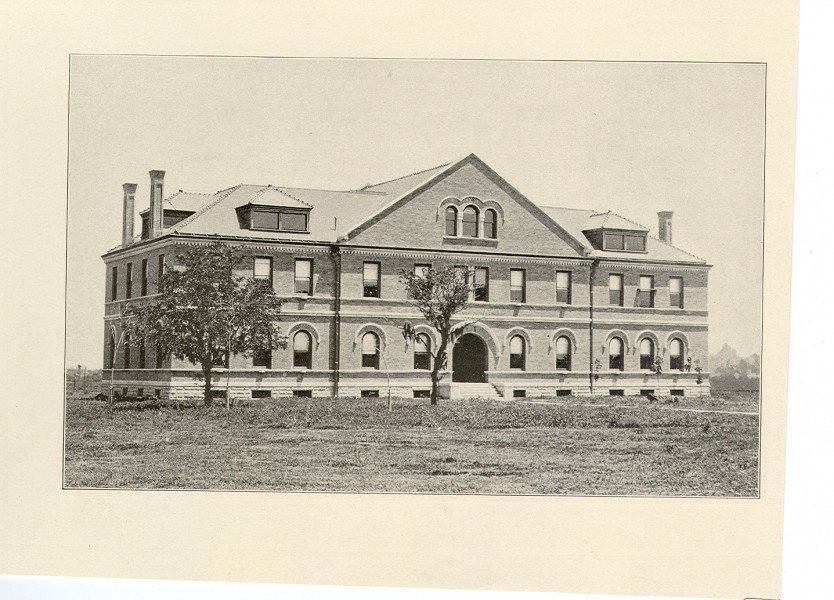

Hebert and Richardson were built in 1894 by the architects Harrod and Andry. Along with Gibson Hall, they were the first buildings constructed on what today is the Gibson Quadrangle.

Nowadays, their main distinction is the fact that they are the only buildings on the Academic Quad that are built in orange brick.

A popular explanation for the difference in the buildings’ façades speculates that during construction, the bricks for the buildings were swapped with the bricks for two buildings at Vanderbilt. The story holds that Vanderbilt has two matching white brick buildings that were originally destined for Tulane.

Vanderbilt does actually have its own “sore-thumb” building, Furman Hall. Built with a castle-like grey stone façade, it stands out on the school’s largely red-brick campus. Students at Vanderbilt have even told similar tales of a swap, proposing that Furman Hall was originally intended for Tulane or Duke University.

There is no evidence to suggest that this ever actually happened. University archivists at both schools did not know of any source to suggest that either story had any validity, and Tulane’s Office of Admission considers the story to be an urban legend.

This reality has not dampened the legend’s continued life on campus.

“I think I heard that rumor on my first tour of Tulane from one of the guides,” freshman Matthew Goldberg said.

In fact, while not a part of the tour script, the story is commonly shared on tours. Green Wave Ambassador Laughlin Grace said that though he has never told the story during tours, he heard it when he toured as a freshman.

“I think it’s just a funny story to tell overall,” Grace said. “Stories like that make the tours more enjoyable, and the prospective students and parents probably like to think they are learning a special secret about Tulane’s history too.”

The buildings were originally designed to be the physics lab and the chemistry building. Hebert Hall — then the “Physical Laboratory” — was the first exclusive physics laboratory building in the South.

At the insistence of Tulane astronomer and physicist Brown Ayres, Hebert was built facing due south “to take advantage of sunlight and enhance the precision of magnetic instruments.” He also requested that the builders use minimal iron to “enhance experiments with electricity.”

Hebert Hall and the Richardson Building actually share more architectural similarities with Gibson than they might appear to at first glance.

Both buildings have Gibson’s central gable, or triangle, surrounded on either side by dormers, small windows which are set into the side of the roof. Their windows and entrances repeat the shape of Gibson’s expensive stone arches, while the trims along the bases echo the rusticated limestone used for Gibson Hall.

An early sketch of Tulane's Gibson Hall, eventually built in 1894 without the tower. pic.twitter.com/9ynKrFTs9w

— Richard Campanella (@nolacampanella) November 23, 2016

After a 1979 expansion, the physics building was rededicated Hebert Hall, after Louisiana congressman and Tulane alumnus F. Edward Hebert. The building was the subject of a 2017 USG resolution criticizing the school for naming the building after a segregationist and calling on the school’s administration to rename it.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Tulane University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Leave a Comment