On the 1619 Project and looking for Black justice

November 13, 2019

Juharah Worku is a research associate for Professor Selamawit D. Terrefe

The Amistad Research Center hosted the latest installment of “Conversations in Color,” a free cultural series centering authors and artists whose work focuses on social justice, this past Friday.

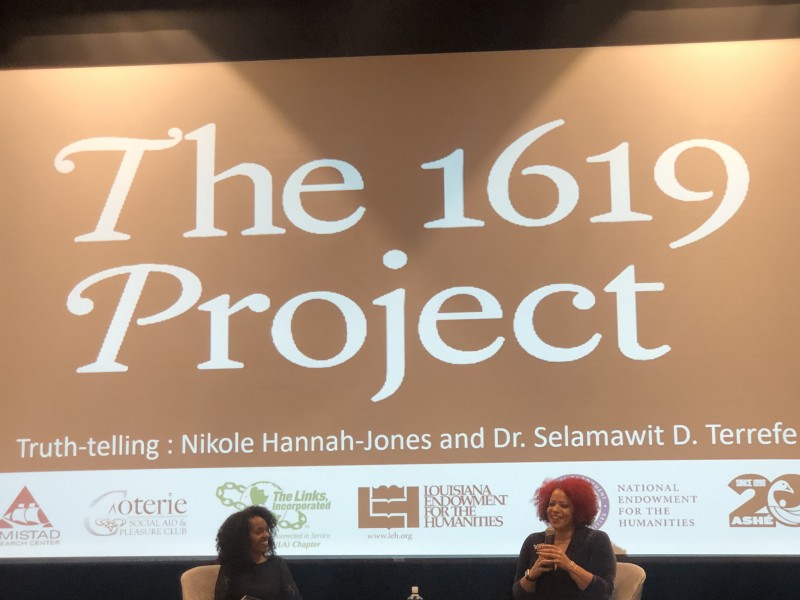

The event, titled “Truth-telling: Nikole Hannah-Jones, Selamawit D. Terrefe and the 1619 Project,” featured Tulane Professor Selamawit Terrefe in discussion on the power of history and representation with Nikole Hannah-Jones, an award-winning investigative reporter covering racial injustice for The New York Times Magazine and creator of the landmark 1619 Project.

The 1619 Project was inspired by Hannah-Jones’ own experiences growing up as a Black American. As a high school student, Hannah-Jones found herself yearning for an in-depth history course that included a fully-fleshed, multidimensional Black history. She cites her own experience in a Black Studies course in high school as providing her with an “insatiable appetite” for history and truth.

It was in this course that she learned of the significance of the year 1619. According to the project, “In August of 1619, a ship appeared … near Point Comfort, a coastal port in the English colony of Virginia. It carried more than 20 enslaved Africans, who were sold to the colonists. No aspect of the country that would be formed here has been untouched by the years of slavery that followed.”

Four hundred years later, the Times project speaks to the ways slavery completely altered the course of American history. Authors, academics, poets and photographers contributed works in an effort to reframe how the country understands slavery. In doing so, the project allowed the general public access to Black American historical narratives often erased from American history. Hannah-Jones and Terrefe’s discussion was as engaging as the project which it centered — the two discussed the legacy of slavery in the U.S. and how it impacts the daily lives of Black Americans through mass incarceration, capitalism and democracy.

But what resonated the most was the audience. The event itself was hosted at Ashé Cultural Arts Center and attracted members of both the Tulane and Greater New Orleans community. Leaving Tulane and entering a Black space, in which people from vastly different backgrounds came together to discuss the ways that history lives on and informs the present, was a powerful experience.

This project, and conversation, empowered Black elders amongst the crowd to bear witness to a moment that confronted the 400-year erasure of their ancestors’ and their own contributions to this country. I sat amongst friends, community members and loved ones and felt that I was able to honor ancestors — those whose lives had been most brutally dishonored in life — in our memory.

Tulane has much to learn from the 1619 Project and truth-telling. Moments like renaming Willow Residences to Décou-Labat are small — and minimally publicized — victories in the history of Tulane and its treatment of Black people. The namesakes and benefactors of the majority of the buildings on this campus have directly profited from the exploitative, dehumanizing institution of slavery here and in the Carribbean, where corporations like the United Fruit Company have exploited indigenous land and labor abroad and subsequently donated to our university.

It is within this historical context that students wear costumes that mock and dehumanize indigenous people and Muslims. It is on this campus where fraternities can build sandbag “Make America Great Again” walls, and where organizations with Affirmative Action Bake Sales within their organization’s chapter handbooks are funded with our Student Activity Fee.

Within this same institution, multicultural organizations must present justification and reasoning as to why the events that sustain their retention as students are necessary to a student government that has the power to decide whether or not these organizations are able to even function. Les Griots Violets, a coalition of Black women organizing for an anti-racist Tulane, have attempted to rectify this institutionally by successfully passing legislation calling for Tulane University to implement an Equity Fee so that organizations and departments that support marginalized students have sufficient funding.

When asked for wisdom she could impart to students who, Hannah-Jones says, “To me, the whole reason you exist in these institutions is to subvert them, to have a chance to actually use the power of these institutions to change the narrative of our people. So that is what you do, you don’t go in there and just exist. You go in there, and use their forces to disrupt”.

This conversation and project expands well beyond that Friday night. We must begin to build and sustain an anti-racist community where we might truthfully discuss the power and legacy of our university – its research capacity and financial wealth are only made possible by the exploitation of enslaved Black people. Rhetoric and representation in media render subjects – including Black people – invisible, visible and/or hypervisible in the narrative of history. But history, combined with policy, constructs the reality of our subjectivity. The narrative of Tulane University is still being written, and only in the light of truth might we know the full extent of what we must disrupt.

Leave a Comment