I’d like to think racism doesn’t exist, on bell hooks

February 5, 2020

*bell hooks as an author intentionally leaves her name lowercase

I see the photo of him on my Tulane ID card. The smile is ear-to-ear, wider than his mouth has ever been. In his eyes, I can see a blind gleeful optimism, a surging desire to throw himself into all things college. He is not even a freshman, only a newly graduated high school senior posing for his Splash Card picture during orientation. I sit here now, counting my last months of my college experience and sometimes wish that I could go back to being him.

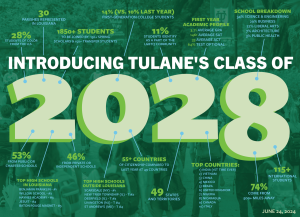

Growing up in Roswell, Georgia, my academic understanding of racism and other forms of identity-based oppression was highly limited. You could not even say “white” in the classroom without a teacher requesting to see you after class. My community was approximately half white and half Latinx and Black. However, my high school was informally segregated, pushing the white and Asian students into AP and Honors classes while tracking Latinx and Black students in the remaining classes. I thought I was living in a blissful white bubble of students all guaranteed the same opportunity to succeed.

I entered college with that same optimism. I readily welcomed white people into my life as I had always done throughout high school. I cared about fighting injustices because I believed it was the morally right thing to do, not because I viewed it as survival tactic, as I see it now.

My schedule began to become shrouded with learning about my own oppression. My classes were discussing critical race, feminist and queer theory. My free time would lend itself to campus organizing against racism and sharing my experiences of discrimination in community facilitation. My worldview shifted drastically, and in every single aspect of my life, I began to see the systems of identity-based oppression at play. I couldn’t go to sleep without racism on my mind, and I couldn’t wake up without breathing it in the air.

I first learned of theorist bell hooks in an introductory gender and sexuality studies course. We studied her essay “Theory as Liberatory Practice” in which hooks points to theory as a form of healing practice, an opportunity for someone to make sense of what’s going on in their life. To hooks, theory can be liberation and intervention in an understanding of why situations in our lives occur. When first learning this, I found some peace of mind. I looked to theory to rationalize my experiences of discrimination and understand the hierarchal levels of the world. I hoped this would be the fuel for my flame of activism.

Instead, I wonder whether I have become cynical. Four years after taking courses that interrogated the experiences of discrimination people of my shared identities face, I can’t live anything in the same way that I did as an unknowing 18-year-old freshman.

Immediately upon meeting white people, I am hyper-aware of the different treatment that I am receiving. I can feel eyes much more intensely as I walk into a grocery store and everyone turns to look at me.

Four years later, I now have the words. I have the scholars, academics and theorists telling me that my life experiences are not what my white straight counterparts are facing. I walk throughout my daily life with thoughts of racism crowding my mind. It permeates my life experiences. Sometimes I wonder how I could see the world differently without this lens.

I think back to pre-college Shahamat. I envy his optimism, his benefit of the doubt and his blindness to the systems of oppression around him. I’d like to think that racism doesn’t exist. However, I think back to hooks — theory as a liberatory practice.

I find her essay both unsettling and comforting. Unsettling in that people of marginalized identities can go decades without ever fully understanding the influence of oppression in their daily life experiences. They might not ever recognize the control of white supremacy in our culture or become aware of the judgemental gazes turned upon them.

Comforting in that theory can be liberation and intervention. Theory criticizes our life experiences not for the purpose of making marginalized people pessimistic, but for the ability to recognize injustice and fight for liberation. Theory allows us to understand the conditions of life that should not be tolerated.

I thank bell hooks for driving me to assess my own life through a lens that has not been chosen for me. hooks has given me the ability to balance each cynical thought that passes through my mind with the hope of freeing myself from the conditions that hold me down.

Leave a Comment