Colonial legacies still stand strong at institutions of higher education

March 5, 2020

The following is an opinion article and does not reflect the views of The Tulane Hullabaloo.

As a Paul Tulane Award recipient, I am constantly negotiating between two poles: while I am truly grateful to have this opportunity to attend Tulane tuition-free, I was, and remain, uncomfortable bearing its name. I was never meant to benefit so greatly from Paul Tulane’s legacy. Paul Tulane, like the namesakes of so many other universities, was dedicated to the success of white students while actively advocating for the oppression of people of color. This dissonance has plagued me during my time at Tulane. How can I benefit from the legacies of people who, were they alive, would never have wanted me to reap these rewards?

Dark colonial remnants such as scholarships and buildings named for racists are glaring across Tulane’s campus, but they’re rarely spoken about. Recently, however, Tulane has found itself unable to escape conversations of its past.

Last Thursday, the Tulane administration took down the iconic Victory Bell in front of McAlister Auditorium. A statement released that day explained that the bell was removed because it was originally a plantation bell. However, the Victory Bell represents just one small part of a much larger history of violence at Tulane — a history that remains on display. Considering Tulane’s position as an elite, southern, predominantly white institution, it’s not surprising that the school has tight ties to oppression. Despite Tulane’s fraught history and contemporary racial landscape, these vexed dynamics are often dismissed or trivialized on campus.

Much like Tulane removing the bell, in 2015 Yale University renamed residential college Calhoun College, named for alum and former vice president John C. Calhoun, to Hopper College, in honor of computer scientist Grace Hopper, claiming that the university was making moves to become more welcoming to diverse students. While this alone was certainly a move in the right direction, it’s a small win against the backdrop of a much larger tradition of oppression. Yale’s campus still bears Calhoun’s name on the residential building and a statue of him stands tall on the school’s grounds.

It’s not enough to remove or rebrand superficial remains of colonialism. Not only does Yale continue to glorify Calhoun — and others like him — through other icons, but the rebranding attempt doesn’t recognize the fact that Elihu Yale built his wealth on the backs of enslaved people.

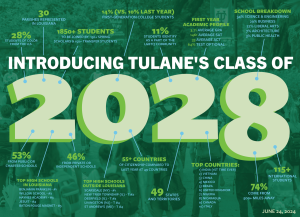

Tulane’s removal of the bell doesn’t acknowledge how deeply racialized the foundation of our campus is. The history of our school manifests itself in so many other, more insidious ways. Our colonial legacy lives on through our 70% white demographic and the casual, daily discomfort that students of color feel. Acknowledging how oppression built the base of Tulane may not be great for the school’s reputation, but it’s a crucial step towards progress.

Higher education in America, and other imperialist nations, will never be able to fully shed its legacy of oppression. But they should never try to deny or hide it. Hiding this history expresses a desire to pretend that it never happened and maintain an image of equality and progressiveness on campus, but it’s too late for that. While the Victory Bell was removed under the guise of making the school a more inclusive place, it was ultimately a shallow and insufficient act. If schools truly want to progress towards a more equal campus, we need to talk about this history. We need to question why that bell was displayed on campus in the first place, how Tulane itself even came to exist.

If Tulane and other institutions are genuinely invested in addressing the school’s oppressive past, they should invite criticism and discourse. Coloniality will forever define the history and the present of schools like Tulane — that’s the stark truth. So, instead of simply hiding mementos such as the Victory Bell away, we need to make the active choice to educate ourselves and those around us about our environment, our privilege and our histories. Only then will we make true strides to becoming a safe environment for all.

Leave a Comment