Could the coronavirus pandemic offer an opportunity to improve the American welfare system?

April 1, 2020

Matthew Wu is a senior majoring in Political Science and minoring in Economics. He is currently conducting research on America’s social welfare system.

Last week, President Trump signed a $2 trillion stimulus bill intended to blunt the economic effects of COVID-19. The bill was needed not just because of the economic fallout from the pandemic, but because our safety net was woefully unprepared to handle it. The crisis has much in common with past events in American history that have presented an opportunity to improve our safety net to keep Americans out of the clutches of poverty. Those moments were not taken advantage of, nor does the recently passed stimulus bill take advantage of the present moment either.

We could have to fall back on that safety net someday – meaning we could benefit if the novel coronavirus motivates a real improvement to it.

As college students, few of us will be receiving a “relief check” — only those who are responsible for a majority of their financial support will receive one — despite the fact that many of us are enduring financial hardships because of the pandemic.

Stimulus checks will also exclude the over 15 million social security beneficiaries who don’t file taxes annually because their income is too low, unless they file additional information with the IRS.

The other provisions include a temporary expansion extension of unemployment benefits, small business loans and corporate aid. In sum, the provisions of this bill do not improve our safety net in the long-term.

As a senior at Tulane, I am completing an honors thesis which argues that America’s social safety net is lacking in part because of our uniquely “American ethos” that stubbornly insists that the market is the proper provider of welfare. This ethos explains the limited safety net for society’s most vulnerable.

While this crisis has much in common with other events in American history that have led to only a temporary expansion of our welfare state, this moment should be a wakeup call about the essential role of social welfare in our economy, inspiring legislation that will achieve a permanent improvement.

The U.S. welfare state owes much of its character to its origins in disaster relief. In the early days of the American republic, politicians were preoccupied with institutionalizing a prevailing political, economic and social philosophy to address the immediate problems of a new nation.

Because they assumed people ought to ensure their own well-being regardless of most external circumstances, assistance was at best a tangential issue, occasionally considered in response to major, one-off disasters.

But there have been moments in American history when achieving a substantive expansion of our safety net became momentarily feasible.

The Freedman’s Bureau was established after the Civil War to assist those who were formerly enslaved. It lasted only seven years. The Great Depression led the federal government to establish Social Security, the country’s most generous universal program. Even so, it was one of only a few of those programs to survive long-term. Two of the key programs from the New Deal, the Civilian Conservation Corps and the Works Progress Administration, were stopgap measures intended to temporarily relieve unemployment.

In the 1960s, rising inequality enabled President Johnson to credibly argue that the vulnerability of the poor was due more to racism and regional disparities than their own moral failings. As a result, Medicare and Medicaid were passed, but the programs were defined by the distinct “deservingness” of recipient groups. The elderly had “earned” universal, federally-funded and -administered health coverage. The poor, however, were relegated to more meager state-based programs with varying eligibility requirements.

Even that progress was all but negated since the 1980s, with rhetoric that demonized those on welfare and policies that devolved even more responsibility to states. Many states have passed laws tying access to social assistance to narrow eligibility requirements designed to shame the poor, ostensibly to avoid creating dependency and to provide tax relief to “deserving” Americans.

Because of the concern with deservingness, the ethos of universal social assistance never took hold in this country. The concept of temporary disaster relief, however, remains as strong as it has ever been. That is why the current stimulus package consists of loans, one-time payments and a temporary extension of unemployment benefits, among other things.

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell made this point on the Senate floor: “This is not even a stimulus package. It is emergency relief.”

We are witnessing the powerful combination of an inadequate social welfare system and a pandemic here in New Orleans. Louisiana has one of the highest poverty rates in the country, meaning health disparities are also high. The Louisiana healthcare system ranked behind all but six states in a 2019 Commonwealth Fund assessment.

Given these facts, it should not be surprising that the Kaiser Family Foundation estimates that about 43% of our adult population has a higher risk of serious complications if they contract COVID-19.

Even after the Affordable Care Act, over 27 million Americans still don’t have health insurance, and millions more aren’t adequately covered. Approximately 50% of food stamps participants are food insecure, and the $1.40 per person per meal allotment is often insufficient to provide for adequate nutrition.

If you could be financially ruined by a medical event outside of your control, and if you could be unable to feed yourself adequately if you lose your first job out of college, are you satisfied with our safety net as is?

Like Hurricane Katrina, the COVID-19 pandemic has laid bare the dramatic – and dangerous – inequalities that define our society. People have lost their jobs, and with them, their employer-sponsored health insurance. The costs of care will be devastating for those who are uninsured.

One woman in Boston was charged nearly $35,000 for her COVID-19 testing and treatment. Both unemployment insurance and food stamps had to be broadened to reach vulnerable groups. Graduating seniors are now about to enter a terrible job market, but many will have massive loans to repay nonetheless.

Even in the face of widespread need due to clearly unforeseen circumstances, discussions of deservingness dominated opposition to this week’s stimulus bill. Lawmakers should not only be concerned about getting the country back on its feet after this crisis, but about how to ensure that our safety net can get people back on their feet following crises that will inevitably occur.

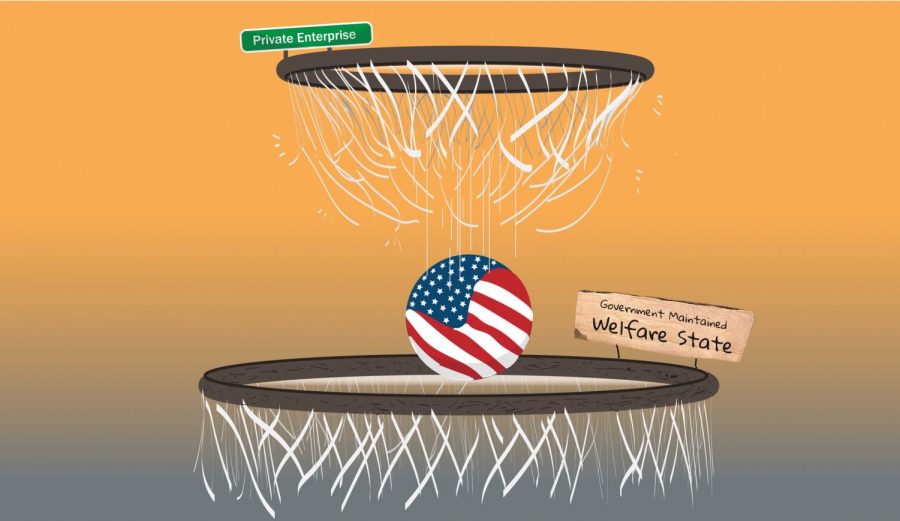

When the pandemic has passed, most Americans will know someone who has had to conduct a trust fall with our safety net. As the economic impact of COVID-19 continues to worsen, I hope my generation will see the American safety net for what it is: less a “net” than a façade, one that is neither generous nor broad enough to lift people out of a state of vulnerability.

The memory of this pandemic will be forever ingrained in our political memory — I hope we use it for the greater good.

Leave a Comment