Tulane students campaign to implement mandatory blind grading

September 16, 2020

Over the past few weeks, Tulane’s campus has seen protests against the presence of Tulane Univeristy Police Department, campaigns denouncing the Greek life system and a faculty-led strike against racial injustice.

These movements and others that vocally condemn institutions of oppression are crucial, but alone, they are not enough. The goal of any social movement is to implement change at every level and combat manifestations of oppression.

The question thus arises as to how we transform this momentum into sustainable change. One initiative at Tulane is dedicated to long-lasting change by implementing a mandatory blind grading system.

Blind grading hides a student’s identifying information, specifically their name, and replaces it with an ID code or randomly generated number. That way, graders can’t see which student’s assessment they’re grading.

The initiative to make blind grading mandatory for all classes was first conceptualized by Undergraduate Student Government senator Mia Harris. Since then, she has been joined by fellow senator Da’Sean Spencer and Ingeborg Hyde, vice president of academic affairs.

The justification of blind grading is that students, particularly those from marginalized backgrounds, are negatively affected by implicit biases. Though not necessarily intentional or malicious, professors harbor implicit biases that can manifest in discriminatory grading practices and lead to students getting unfair grades due to their race, gender, appearance or other factors.

“I really don’t want to have other students feel this way, feel like their GPA could be based on something other than their performance or their talent,” Harris said.

Blind grading, while not common in undergraduate classes, is a frequently used grading system in graduate schools, including law school programs. Even within undergraduate institutions, however, blind grading is not an entirely foreign concept. For example, Undergraduate Learning Assistants at Yale are expected to use blind grading mechanisms, though the same is not required of professors.

The idea of a blind grading system is promising for several reasons. For one, it’s incredibly simple to implement in undergraduate classes. Commonly used platforms such as Canvas, which is currently used at Tulane, have built-in features to allow blind grading. Establishing a blind grading system, then, wouldn’t require any extra work on the grader’s side aside from choosing the feature. Additionally, it’s worth mentioning that a blind grading system doesn’t just benefit students, but can be seen as a protective measure for graders. Being unable to identify the student behind each assessment means graders don’t have to worry about projecting their biases, nor do they have to worry about being accused of discriminatory practices.

Nevertheless, blind grading is still subject to controversy. The primary issue with blind grading is that it doesn’t allow for a grader to track a student’s progress throughout the class. Blind grading doesn’t eliminate personal interactions between professors and students, however. Students would still have the option to approach their professor at any time to ask for help or discuss an assessment.

The work of initiatives such as this go far beyond just altering the grading system. “This kind of work sets a precedent and continues to open the door for other changes,” Spencer said. Initiatives like this one are part of a larger movement for equality. While they are intended to enact change individually, these programs also act as propellers for further reform.

When it comes down to it, implementing blind grading systems is meant to ensure that students don’t face stress over possibly being graded unfairly due to their race, gender, appearance or any other factor. “At the end of the day, it’ll give students peace of mind to know that their work is being graded on their merit and not based on anything else, which is the goal of academia,” Hyde said.

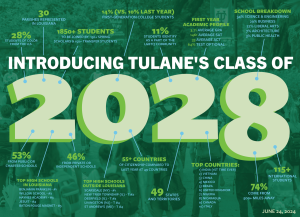

As the Tulane community continues to build on the momentum created by the recent racial justice protests, students and faculty need to consider not only how our actions will affect the immediate community, but how it will affect students of Tulane years from now.

“I just want to encourage students to think about other students,” Harris said. “We all need to take sustainable action, change like this that is truly going to affect the life of someone at Tulane six years from now.”

Anyone interested in sharing their experience with academic discrimination can complete this form or use the QR code below.

If you’re interested in joining the blind grading initiative, reach out to Mia Harris at [email protected].

Baffled Student • Sep 21, 2020 at 11:06 am

If your going to go with blind grading then do away with affirmative action. If you want systems to be blind, college applications shouldn’t ask what race, gender, ethnicity, or any of your other soft meaningless traits. Oh but wait, that gets rid of the unfair advantage non-white people have getting into colleges. Stop scapegoating to an intangible identity and actually study to get a good grade.

Amy George • Sep 19, 2020 at 10:50 am

A single policy ignores the variety of assessment types we, your professors, use. My exams are open-ended personalized essays. I use the information from student exam production to help me identify which students need additional support from me. I write to students who are struggling directly. I speak to students in class when I see that their exams are showing weaknesses we can work on together. To think that a student should be the one to approach their professor when their exam results show a weakness demonstrates a lack of understanding of how struggling students respond to lower grades (hint: it’s not generally by reaching out to their professor themselves). In short, this proposal seems well-meaning, but I think it demonstrates a lack of awareness of how different various classes are and the myriad uses of exam data for learning.

Cariol • Sep 19, 2020 at 9:38 am

Arguments for and against blind grading aside, this just isn’t a matter on which students have a say. Members of the faculty have the responsibility and authority to decide how their classes will be graded. They will not allow students to make this decision for them. Nor should they.

Anonymous • Sep 18, 2020 at 8:46 pm

If you go with blind grading in the name of fairness, then the same principles should be applied to admissions and scholarships

John I. Gilman • Sep 17, 2020 at 11:02 pm

Blind Grading- ridiculous!

Concerned Citizen • Sep 17, 2020 at 8:24 pm

Just say you wanna complain about something and go. Majority of students would support this. Maybe you should send ur kid to the state school if you don’t like it.

Robert E Hunter, JD, PhD • Sep 17, 2020 at 8:16 pm

I have my M.S. and Ph.D. from Tulane. Blind grading is an absurdity at a small university. The whole point is your professors get to know you. I guess they would prefer to be known by their SS# or student ID# like the large universities.

Student • Sep 17, 2020 at 5:26 pm

To the authors of the previous comments,

When your kids are graded by something other than the academic work they produce, then feel free to make an educated comment. So many credited studies show that professors inherently grade students based on various factors, such as gender, race, favoritism, etc. because just like you and me, teachers are humans too. Blinding eliminates bias and allows each student to receive a fair evaluation of the work they produce.

I hope you choose to send your student to a smaller university or an Ivy League school because …oh wait…they have blind grading too! (and clearly Tulane students value an equal academic playing field, unlike you).

Arnold Ferguson • Sep 17, 2020 at 2:40 pm

I believe this BLIND GRADING is a pile of something.

Jill Melanie • Sep 17, 2020 at 2:09 pm

Really? My kid will just be a number? If I wanted that for my student I’d save a lot of money and send them to a larger state school. The appeal of a small university, such as Tulane is the personal connections that they make with their Professors. Plus, if a student wanted to remain anonymous, then how would they go to the Professor for in person extra help? “Hi, I’m number 456 and I need some tutoring on such and such a project”. Would the student then wear a face covering ( in addition to the required masks) to hide who they are? Come on! If you’re going to fight for a cause, there is certainly no shortage of worthy causes out there.