Tulane professors participate in Scholar Strike

September 13, 2020

Various Tulane professors, including Matt Sakakeeny and Mohan Ambikaipaker, participated in the nationwide Scholar Strike on Tuesday.

The strike was organized over social media, via posts by Anthea Butler, a professor of religious studies and Africana studies at University of Pennsylvania, and Kevin Gannon, a history professor at Grand View University in Iowa.

Butler was inspired by NBA and WNBA athletes who chose to refrain from playing their sports in light of police violence against black people in the U.S.

https://twitter.com/AntheaButler/status/1298736961184825345

“It soon gathered a very fast team of lots of professors around the country, thousands even participating in the strike,” Ambikaipaker noted. “I am fully pledged on the scholar strike call.”

This meant refraining from his normal duties with the university on Tuesday and Wednesday, including teaching classes is his field of critical race theory and cross-cultural analysis.

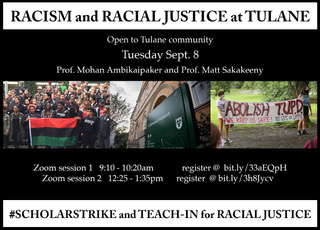

In addition to participating in the strike, Sakakeeny and Ambikaipaker led virtual teach-in sessions around the topic of Tulane’s history of white supremacy, open to the Tulane community.

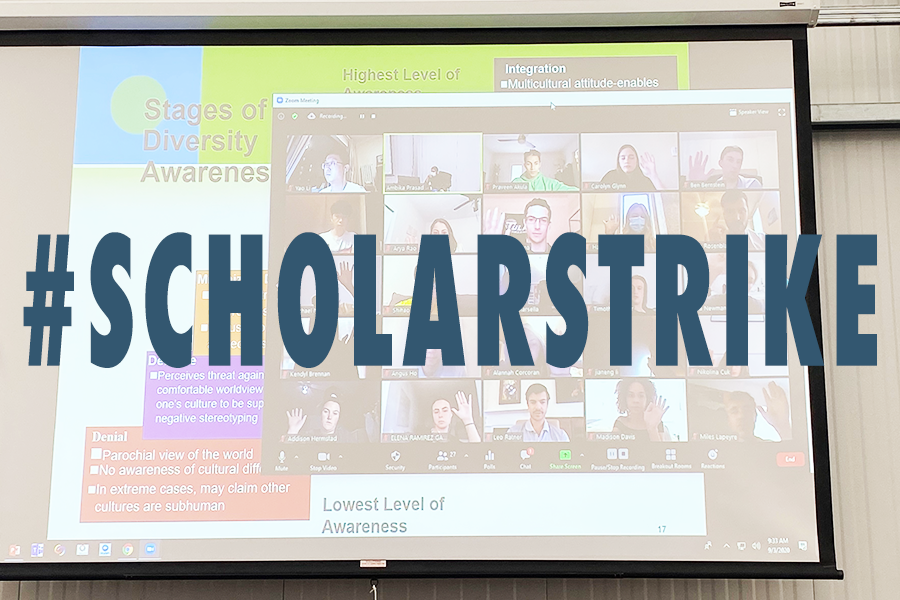

Almost 100 members of the Tulane community participated in the professors’ second Zoom presentation on Tuesday. The event began with a PowerPoint entitled “Tulane as a White Supremacy Racial Project.” Ambikaipaker delved into slides on significant names in Tulane’s founding and their association with white supremacy. These included Paul Tulane and his 1882 donation to the university designated “for the promotion and encouragement of intellectual, moral and industrial education among the white young persons in the City of New Orleans.” Similarly, Josephine Louise Newcomb’s donation was to coordinate the first degree-granting, white women’s college in the nation. Randall Lee Gibson, the namesake of Tulane’s landmark entrance, inherited his father’s involvement in the sugar industry and volunteered with the confederacy. The university’s first president, William Preston Johnson, was a colonel in the Confederate army and aide to Jefferson Davis.

This history of white supremacism continued into the 20th century as Tulane reluctantly desegregated when the Ford Foundation refused to provide Tulane with grants until they integrated. They finally desegregated in 1963 with the admittance of graduate students Pearlie Elloie and Barbara Guillory Thompson.

Sakakeeny and Ambikaipaker tied this historical conversation back to its impact on present-day Tulane. This included a discussion surrounding university workers, policing and the physically constructed “Tulane bubble.”

Sakakeeny and Ambikaipaker’s research and social justice partnership began earlier this summer when they collaborated on an op-ed titled “Bringing students back endangers university workers.” In the piece, Sakakeeny and Ambikaipaker explained that working-class people of color, such as employees of the university’s private dining service Sodexo, will be disproportionately impacted by Tulane’s decision to return students to campus this fall.

Sakakeeny and Ambikaipaker repeated these sentiments during the Scholar Strike, saying that Tulane has chosen to contract with Sodexo in order to not be held responsible for workers.

“There is lots of evidence that Sodexo workers that have tried to unionize and get collective bargaining rights or better pay have been fired,” Sakakeeny said. “There’s absolutely a documented case of the previous Tulane President Scott Cowen [disciplining] four Tulane students who were trying to organize around the rights of those workers.”

Ambikaipaker continued that “it’s almost impossible to get people of that vulnerability in the university to share their experiences because they will be disciplined for it … workers are rotated out of buildings so that they don’t develop relationships and Tulane has enabled this precarity.”

Sakakeeny and Ambikaipaker see this second-class treatment of university workers as deeply correlated with broader violence faced by Black Americans.

The Scholar Strike occurred just over one week after Tulane students organized an Abolish TUPD protest on campus.

Both Sakakeeny and Ambikaipaker resonated with the message of the protest with Ambikaipaker saying “it is time to move beyond policing as a means of addressing the issues and even so-called safety that goes beyond policing.”

Ambikaipaker discussed in his teach-in the disparate treatment of Tulane students and local New Orleanians by police on similar crimes including possession and distribution of drugs. He referenced a 2013 incident where members of the Kappa Sigma fraternity were involved in a raid of $10,000 worth of drugs. The students were later returned to full academic standing with the university. He continued by saying that Tulane is designed to enclose itself in the ‘Tulane bubble’ and prevent Black New Orleanians from entering.

Ambikaipaker and Sakakeeny recalled a Tulane faculty meeting where a faculty member suggested that the university use TUPD as a means of enforcing mask wearing on campus. This caused Sakakeeny and Ambikaipaker to further question why individuals call in police to handle issues of public health, mental health and social work when they have seen the violence that police have used against Black Americans.

“The kinds of work that people think police do is a small percentage of police work,” Ambikaipaker said. “Detective work is only 15% of the police force.”

Sakakeeny also called attention to the symbolic nature of the email sent from President Mike Fitts to the Tulane community following the murder of George Floyd in late May. The email begins by saying, “On Saturday, I shared my despair over the recent stories of injustices against African Americans, including the death of George Floyd,” and continues later by saying, “We stand with the many police officers, including our own Tulane Police Chief Kirk Bouyelas, who has joined with police chiefs around the country to condemn these acts.”

“Literally in the same breath of condemning police murders [Fitts] is showing his support for the Tulane police department who make a symbolic gesture around condemning the acts,” Sakakeeny said.

Ambikaipaker and Sakakeeny noted that Tulane’s decision to remove the McAlister Bell last year due to its correlation to slavery and plantation life was reminiscent of this same level of symbolism and “tokenism” rather than productive change.

Sakakeeny believes that the university needs to do more to reckon with racism “all the way down” rather than “[putting] a bandaid on something” as he believes Fitts’ Presidential Commission on Tulane Values and Anti-Racism has done.

“The Presidential Committee on Race has essentially resulted in the hiring of a diversity officer, who’s new, and trying to diversify the student body through the admissions office,” said Sakakeeny. “And other than that there has not been a lot of activity to come out of that institution.”

Ambikaipaker instead encouraged a shift toward the tough questions of discriminatory practices.

“How many Black faculty do we have? And why has that happened?” Ambikaipaker said.

“I urge you to go to the president and provost website and just go through the pictures,” Sakakeeny said. “There’s a gender problem there too.”

Both professors wish to signify to Tulane students that it is possible to create these autonomous forums to discuss issues such as racial relations on campus, as they did this week.

“This was our partial efforts and we want more people to be doing it,” Ambikaipaker said.

“And to the student readers of The Hullabaloo, we see you. We see those of you that are out there and trying to make change and we support you,” Sakakeeny said. “It’s comforting to know that some of you out there are willing to question the university and essentially a unilateral decision on their part. So I would say to Black Student Union, to SOAR, to the Abolish TUPD [group] … don’t stop, don’t give up.”

Larry Masters • Sep 15, 2020 at 3:06 pm

I agree with Prof. Amikaipaker, Tulane is a terrible place. I assume he did not know the history when he took the job. Now that he knows how evil Tulane is, he can show his conviction by refusing to take money from the University. He can show even more conviction by leaving his job here and discarding his Phd from the University of Texas (another corrupt, white supremacist institution.)

Is it really a “strike” if you are still getting paid? I think is just taking not showing up for work.

Let’s be honest, everybody (or pretty near everybody) in the 1800’s were racist by todays standards. Those attitudes continued well into the 1900’s and are dwindling today. This push to judge the past through the lens of 2020 is both silly and pointless. Should we tear up streets laid out by racists 200 years ago? Should students not rent shotgun doubles built by minorities at reduced rates? When does the silliness end? What is the end game?