OPINION | Despite changes, undergraduate resources remain stratified

April 28, 2021

In 2018, Tulane University constructed the $35 million Goldring Woldenberg Business Complex. Developed to bridge the two buildings that once comprised the business school, Goldring/Woldenberg was designed to enrich the workspace for business school students by facilitating collaboration through architecture, providing meeting spaces and mitigating foot-traffic issues. The construction project “is designed to meet the changing needs of business students and faculty,” Dean Ira Solomon said in 2018.

The A.B. Freeman School of Business at Tulane enrolls slightly more than 3,000 undergraduate and graduate students. While Goldring/Woldenberg is not necessarily meant to house the full extent of those students at once, it is far more spacious than many other learning spaces on campus.

It is evident that the design of Goldring/Woldenberg was extensively thought-out and took into consideration what layouts and structures best suited a student’s needs.

The building has an indoor-outdoor feel, with large glass windows that overlook McAlister Drive and connect it to Tulane’s main campus. The complex features open space that allows one to see from one floor to another or down to the main lobby. Every space in Goldring/Woldenberg is a potential workspace — there are both classrooms and smaller workspaces as well as public tables meant for one or two students that encourage independent studying without making a student feel isolated. This design likely exists to promote productivity.

Goldring/Woldenberg allows business school students convenience, as class and studying can be done in the same place with all the same resources available. Compared to other buildings and residence halls on campus, the business school is more accessible with ramps and elevators.

The business complex itself is not an issue; in fact, it goes to show that Tulane can successfully dedicate its resources to creating a space that enriches learning. The problem is that the business school and majors within it are the only disciplines that have received a comprehensive academic environment with all of its needs in mind.

Tulane is, first and foremost, a research university, but it advertises that liberal arts are the backbone of its esteem. “Tulane pairs the resources of a large research university with the benefits of a small liberal arts college. It is one of the few research institutions in the country where almost all undergraduate courses are taught by full-time faculty, small class sizes are the norm, and faculty members are both accessible and approachable,” the Tulane website says.

Further, liberal arts classes are required as part of Tulane’s core curriculum, which intends to expose students to “academic foundations in writing, foreign language, scientific inquiry, and cultural knowledge.” If liberal arts are essential to Tulane’s mission and to the quality of the education it advertises, why is there no comprehensive liberal arts or humanities school? Additionally, Tulane is ranked 13th best school for public health, and the current Public Health and Tropical Medicine school is tucked away towards the back of campus, unrenovated, and seems to have none of the thoughtful design that the business complex has.

Liberal arts classes are scattered around campus, but often take place in Newcomb Hall, McAlister or Dixon Auditoriums, the basement of Howard-Tilton Memorial Library, or most recently, the temporary classrooms on the quads. While these locations are nice buildings, they are in no way suited to house discussion-based, collaborative courses. English classes are stuck in classrooms with desks attached to chairs, lined up in rows so that students are only able to see the back of the person in front of them. These seats are difficult to move into arrangements that facilitate discussion and collaboration, which is an essential aspect of productive humanities courses. Discussion sections of lecture-style classes often go silent because class setups stifle familiarity at a most basic level. How can you talk about literature, art, philosophy, politics or international development when you cannot see who you are talking to?

Humanities students are put at a disadvantage if the location of their class diminishes the quality of their education. Equally important, so are humanities teachers. Learning — especially in the humanities — should be collaborative between students and teachers. The setup of current liberal arts classrooms literally elevates the teacher above the student and almost forces a teacher to adopt a lecture-style class, which suppresses collaboration in what should be an equitable discussion where everyone is encouraged to speak openly. It is unfair to humanities professors to condemn them to settings that make it significantly more difficult to run an effective class.

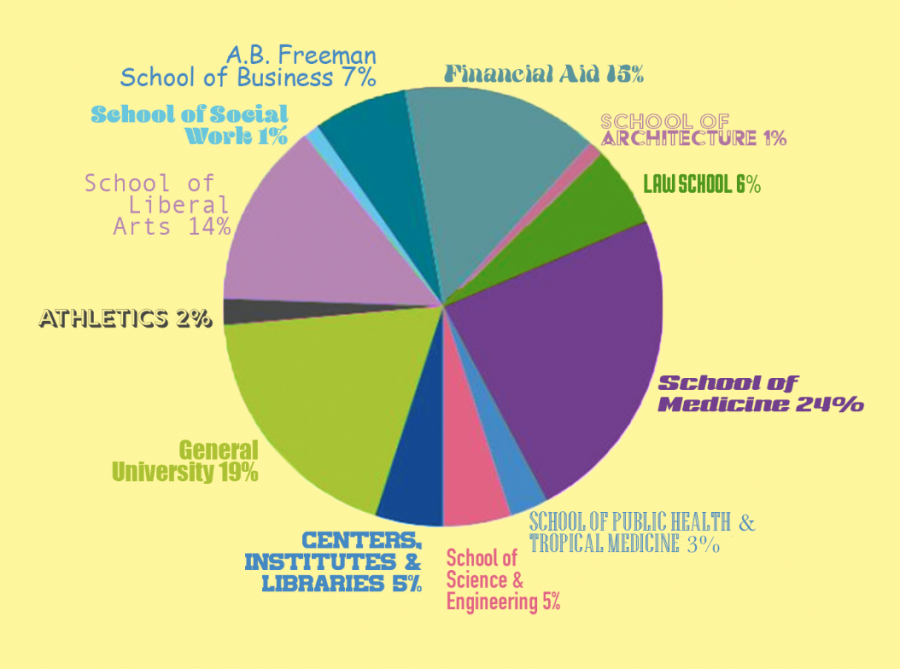

The business school brings significant income into the school, and so money is put into it to continue that pattern. Two years ago, a writer for The Hullabaloo noticed the inequity between funding for the business school and funding for Tulane’s other four schools; since then, endowment percentages have actually swayed more heavily in the other direction, with the school of liberal arts laying claim this past year to 14% of the endowment, compared to the business school’s 7%. It is disappointing to see that, despite this shift, not much has changed in terms of the creation of comprehensive learning spaces. Tulane has an endowment of just over $1 billion and has been able to fund new buildings and programs to accommodate learning around a pandemic. All around campus, free goodies are handed out, and bold advertising campaigns are posted at the front of the Lavin-Bernick Center for University Life that one can imagine were costly. Given that little attention seems to be given to certain schools and academic disciplines, one must wonder if Tulane sees its students and its schools as sources of income rather than communities composed of students and faculty that are just as deserving of resources.

If you visited Tulane before attending, you surely noticed the ostentatious banners that line McAlister Drive. When it comes to advertising, Tulane talks a big game. However, just beyond the flashy signs that draw people to this university, Tulane has a lot of work to do to make its advertisements a reality.

. • May 3, 2021 at 9:52 pm

Stern also sucks!!

I feel like it’s simple: the business school has wealthy alumni that donate back to the business school. Liberal arts majors less so, and SSE alumni will likely donate to their PhD, MD, or other post-grad institution more so.

Redistribute that wealth though, Tulane! Newcomb fourth floor is literally a death trap.