Tulane community alters landscape of NOLA public education

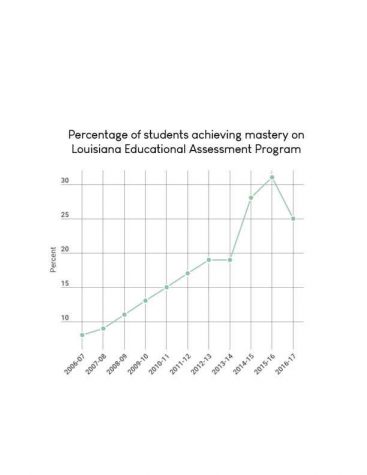

For the first time in a decade, citywide school performance has dropped in New Orleans, according to a recently released State of Public Education Report by Tulane’s Cowen Institute.

The Cowen Institute is a Tulane-sponsored entity formed “to advance public education and youth success in New Orleans and beyond,” according to the institute’s website.

It is one of several Tulane-affiliated programs, offices and initiatives broadly aimed at supporting public education in the New Orleans area. These include the Education Research Alliance, the Tulane Teacher Preparation and Certification Program, the Center for Public Service and Upward Bound.

“I think as a world-class research institution and as one of the largest employers in the city, Tulane has a really important role to play in advancing education,” Amanda Hill, executive director of the Cowen Institute, said.

Dubbed “The Experiment” by journalists and education scholars, the current education system in New Orleans was designed in response to the perceived shortcomings of the pre-Katrina education system. Now, almost all schools are charters – publicly funded and privately managed.

https://twitter.com/EinsteinCharter/status/989132501137481728

Tulane has refrained from endorsing any particular education policies in New Orleans. There is a perception, however, that Tulane and its affiliates are pro-reform. According to Associate Professor of Political Science J. Celeste Lay, this perception does not hold up to reality.

“[Tulane] does not have a position on charter schools or on elected governments or any of these topics with regard to the politics and the coalitions that make up the proponents and the opponents of this system,” Lay, who teaches a course called “The Politics of Education Policy,” said. “Tulane has tried very much to be on the outside of this system. That’s politically a good strategy for Tulane, to not be affiliated with either side.”

Instead of getting involved in the politics of policy, Tulane engages with education stakeholders primarily by providing research and student volunteers at local schools.

SERVICE LEARNING

Tulane often emphasizes its commitment to public service. According to Bridget Smith, assistant director of the Center for Public Service, at least half of service-learning courses involve working with local youth populations through school and after-school programs.

Smith said the majority of CPS-facilitated service-learning projects involve tutoring in local schools, while other projects include Tulane students presenting lessons to local public school students.

Sophomore Kyle McIntyre has worked with local students on two different Tulane service-learning projects — one where he tutored students after school and another where he and his classmates taught international relations concepts to students at Homer A. Plessy Community School in the French Quarter. Sophomore Jenny Ly worked as a reading buddy and teacher’s aide at Lawrence D. Crocker College Prep for one of her service-learning projects.

Prior to beginning their service, McIntyre and Ly participated in CPS-led preparation. Some students and faculty suggest this training is insufficient.

“We do recognize that if students don’t understand all of the assumptions that they might be carrying as they walk into working with any program, any community, [or] negative stereotypes they could be reinforcing … [then] they could be causing harm,” Smith said. “And I don’t even think that a two-hour workshop is necessarily going to fix that either …”

Additionally, Ly said she noticed local students may have been negatively impacted by uninvolved volunteers.

“Sometimes students were apathetic or unenthusiastic when in the presence of students …,” Ly said. “I think that there needs to be an extra emphasis on the attitudes that Tulane students bring to these service-learning locations because attitudes can convey a lot of meaning.”

Because so many Tulanians are involved in local education, some community members have asked students to consider the complexities of the system before they take a role in it.

“A desire to help better public education in New Orleans is great, but this must be driven by an understanding of the backgrounds and cultures of the students we are serving,” Blake LeBlanc, a Tulane continuing studies student and 2nd grade math teacher at Einstein Charter School, said. “If we do not consider this, we will never produce effective change. This is especially important for Tulane students coming from outside of the area.”

TEACHERS

Another way Tulane students serve in local public schools is through Tulane’s Teacher Preparation and Certification Program. The program trains undergraduate students for teaching careers and certifies post-baccalaureate professionals who want to become teachers.

“We definitely make sure to put our students in a variety of schools …” Shannon Blady, director and professor of practice for TPCP, said. “… We really want them to understand what’s going on at all these different settings, and then they can make a decision about what placement is best for them when they apply for their own jobs.”

For Ly, LeBlanc and many of their peers in TPCP, student teaching opportunities solidified their choices to go into teaching. Blady, Ly and others involved in TPCP, however, said they recognize that they are working in a rapidly changing field.

The Cowen Institute 2018 State of Public Education Report finds that that 50.7 percent of the city’s teaching population is African-American. This number is lower than the pre-Katrina percentage of African-American teachers, which was 71 percent in the 2004-05 academic year. It is also lower than the percentage of black students enrolled in New Orleans public schools, which is 79.9 percent as of this academic year.

“We want teachers to understand what our students here go through,” Barrett said. “… A lot of these kids experience trauma at different levels than what I think the teacher workforce here understands … Schools are moving toward doing things in their professional development activities to help stimulate that understanding, but I don’t think that that’s a perfect replacement for having teachers that are from here that teach here.”

Because the Tulane administration and student body are tied to public education and organizations like Teach for America, Tulane is critically evaluating the challenges faced by the city’s schools.

Guest column: New Orleans' next mayor should stress child care, education, Russel Honore writes | Opinion https://t.co/iJ5xk9JlAF

— Russel L. Honore' (@ltgrusselhonore) April 6, 2018

“The good news is that while [the changing field of teaching] is such a critical issue and we do have teacher shortages and demographics have shifted, we also see universities, nonprofit partners and the government coming together to say we’re going to do something about this to ensure that students have high quality teachers,” Hill said.

EQUITY

At the core of many discussions about education in New Orleans, including those related to the shifting demographics of teachers and the dynamics of Tulane service-learning projects, are questions of race, socioeconomics and equity.

“I would argue that the biggest problems in education, the reasons the U.S. doesn’t stack up better internationally, is due to poverty in the country,” Lay said. “Poverty and educational outcomes are very closely correlated with one another. We have more inequality, we have more poverty in the United States than in many of the countries at the top of these scales.”

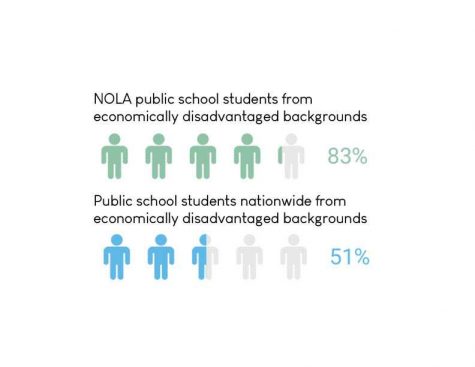

83 percent of New Orleans’ public school students are from economically disadvantaged backgrounds, compared to 51 percent of public school students nationally. Given this fact, sophomore Matthew Weber, who is from New Orleans and attended Benjamin Franklin High School, said he agrees that there is more to remedying education than test scores.

“When you are only thinking about someone as their scores, you aren’t thinking about if they feel safe in school, if they are getting adequate food or transportation,” Weber said. “A more holistic method needs to be used, and I think that’s our first step to improving education standards.”

Hill said equity is at the helm of the Cowen Institute’s work and added that she is hopeful Tulane’s education-oriented initiatives will prioritize equity in the future.

“… I think that there are initiatives at Tulane to, one, increase the diversity of the student body and, two, make the experience for students more inclusive,” Hill said. “I think there’s a lot more work ahead and then it’s certainly just beginning, but I’m glad that it’s beginning.”

(RE)BUILDING COMMUNITY TRUST

Tulane-affiliated offices and initiatives seeking to advance public education must navigate complex issues of equity and a changing teacher workforce. According to some in the field, Tulane must address the perceived lack of trust between its programs and the community.

“There’s still a lot of community members that don’t feel like they’re connected to the public education system,” Barrett said. “And so when you add Tulane into the mix, it’s kind of this, to use an old adage, it’s kind of this ivory tower, like this separated thing from the rest of the city.”

Barrett said Tulane could build trust by engaging with the community and building a relationship that isn’t “top down.” For some students, however, rebuilding trust between the community and Tulane when it comes to education must consist of more inclusive and proactive admissions practices.

“Tulane is like a city on a hill, something you aspire to, but you don’t really believe you’ll ever go there, because most people don’t have the option, even if they have the option,” Weber said.

Ly, who grew up in Jefferson Parish, said that despite her high school being only a few miles away from Tulane, she is one of two students from her graduating class that enrolled at Tulane.

According to the Office of Admission, it has several programs aimed at addressing inaccessibility of education for disadvantaged students in the New Orleans area. Some of these programs include Tulane admission counselors visiting local high school college fairs, hosting application workshops for local students and flying in students for PreviewTU.

“We believe that the work to provide greater access to students in the New Orleans community means early and consistent outreach,” the Office of Admission said in a statement. “To that end we’ve developed several early outreach opportunities and host many school and community-based organizations on campus.”

MOVING FORWARD

Because of Tulane’s far-reaching presence in diverse aspects of education, some members in the field said that the University and its affiliates are well-positioned to elevate public education in New Orleans.

Currently, Tulane’s education-oriented organizations lack centralization. According to Blady, these organizations could be more effective if they worked together.

“I just think we need more of a hub so that we can all kind of help each other and support each other and know what each other’s work and research is about,” Blady said.

In addition to coordinating efforts across Tulane’s many public education-related entities, Barrett and others said that public education remains a complex issue and that researchers and advocates must consider many potential ways forward. Ultimately, he said, there is no magic remedy for improving educational opportunities and outcomes.

“There are all these incremental changes and tweaking [of] a system that had some issues,” Barrett said. “Is it gonna be perfect? No. But I’m not sold on the idea that we have to educate this way – like this is the way the school system should look and that’s final. I just want the best system possible for kids, and I know that sounds idealistic but at the end of the day, that’s what the hell we’re doing here.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of Tulane University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Leave a Comment