Horror, marginalization have always been intertwined

November 5, 2020

For several horror movie enthusiasts, myself included, Halloween is a time to indulge in all our fascinations with gore and fear. While the monsters we see on screen may seem to be nothing more than superficial manifestations of terror, for some, they carry much deeper meanings.

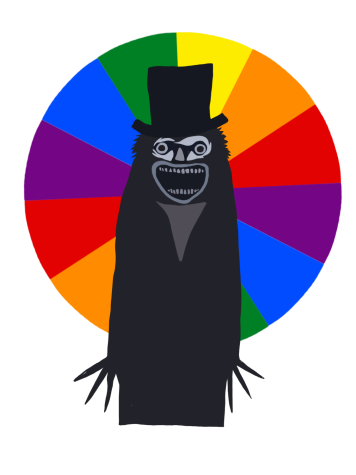

In the fall of 2016, a possibly photoshopped Tumblr meme featuring “The Babadook” listed under LGBTQ movies on Netflix went viral, leading to the film’s titular villain, the Babadook, becoming iconic within queer communities. The film, which tells the tale of a single mother and her son being haunted by a monstrous character from a children’s book, seemingly has nothing to do with queer identity. However, the Babadook’s importance within the queer community goes far beyond a simple Netflix error. What may have started as a joke grew into a genuine queer analysis of the Babadook.

Since the film’s release, queer interpretations of the film has likened the Babadook’s attempts to be acknowledged by the family in the film to queer individuals struggle for self-assertion in straight, domineering households. Despite being a perpetual figure in the household, the Babadook is excluded as the villain of the film, an exclusion that resonates with many marginalized individuals. The Babadook, which is a metaphor for mental illness and grief, is also seen as representative of the trauma that many queer people experience as they navigate coming out, rejecting cisheteronormative standards and reckoning with continued social stigma.

This isn’t the first time that a previously stigmatized or supposedly supernatural figure has evolved into a symbol of empowerment. For example, consider the trope of witches. The Salem Witch Trials are far behind us, but witches remain emblematic of the horror genre. However, in the centuries since the Salem Witch Trials, witches have transformed into a feminist representation of power and opposition to patriarchal ideas. For many feminists, witches, with their outsider status and unique powers, parallel their own lives in the margins of society. While the reclaiming of witches by feminist groups carries an entirely different weight than the queer reclaiming of monsters like the Babadook, both represent the ways marginalized communities see themselves in ostracized characters.

Similar to the Babadook, Pennywise from the hit horror series “It” has also been claimed as a queer icon. In fact, some people like to believe that the Babadook and Pennywise are a horror power couple, affectionately named “Babawise” or “PennyDook.”

However, the queer reinterpretation of Pennywise has been received with serious controversy. Unlike the Babadook, which is seen as a layered and nuanced figure even outside of queer groups, Pennywise is an irredeemable monster. The shape-shifting clown is not symbolic of greater social or personal issues like the Babadook. Rather, Pennywise is solely interested in murdering children. It’s likely that the only reason that Pennywise is considered a queer figure at all is due to the fact that the character is heavily queer coded.

Queer coding — when writers imply that a character is queer, often through costumes and mannerisms, without explicitly stating it — is a highly contested idea. While queer coding is especially controversial in cases of villainous characters, it’s still a frequent occurrence in pop culture. In addition to Pennywise, other figures including Disney villains have been characterized in ways that demonize queer identities. For some, Pennywise is the exact degradation of queerness that the reclaiming of figures like the Babadook combats.

The Babadook is arguably on a different level from the dangerous practice of queer coding, which is perhaps how the figure has remained a staple within queer communities for years. To marginalized individuals who have long found themselves pushed to the outskirts of society, the Babadook is a powerful recognition of their struggles to exist in an oppressive world.

It’s not easy to take a definitive stance on what place monsters have in marginalized communities. The competing views represented in Pennywise and the Babadook prove how nuanced these reclaimings can be.

Ultimately, whether we agree or disagree with monsters transforming into queer icons, we can’t deny that marginalized individuals are drawn to these characters. The same reason why feminists are drawn to witches for their history of persecution, queer individuals are drawn to monsters for their exclusion in standard society. When marginalized individuals empathize with supposed nightmares due to shared experiences of social ostracization, perhaps we have much scarier figures in our society than ghosts or murderous clowns.

Leave a Comment