Sometimes I lie about reading books

December 1, 2021

This article contains content pertaining to sexual assault.

This story is not linear. None of these bits and pieces are bookended neatly before they get the chance to overlap, and yet they hardly seemed connected to each other until recently.

I’ll begin by telling you something incredibly mundane: Sometimes I lie about reading books.

I lied to my suitemate about reading Chanel Miller’s book, “Know My Name”. We spent the Hurricane Ida break together in South Carolina with stacks of novels and poetry, and she had voraciously devoured it.

Just as offhandedly as my suitemate asked, I said “Yeah, of course. I can’t wait for her to come to talk on campus.”

That was in September. I didn’t read anything past the introduction until less than a week ago.

As I sat at my gate waiting to board my plane, I decided that I would finally crack open one of the books I promised myself I would read over Thanksgiving break. I brought three: “Dispossessed” by Ursula Le Guin, a book about structural listening in post-modernity and “Know My Name”. Somehow a book about sexual assault felt like the easiest read of the three.

This time, I got past the introduction. It took me just a few pages to start crying in the middle of the airport. I marked the exact line, on the sixth page:

“I always wondered why survivors understood other survivors so well. Why, even if the details of our attacks vary, survivors can lock eyes and get it without having to explain. Perhaps it is not the particulars of the assault itself that we have in common, but the moment after; the first time you are left alone. Something slipping out of you. Where did I go. What was taken. It is terror slipping out of silence. An unclipping from the world where up was up and down was down. This moment is not pain, not hysteria, not crying. It is your insides turning to cold stones. It is utter confusion paired with knowing. Gone is the luxury of growing up slowly. So begins the brutal awakening.”

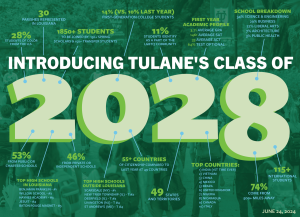

I was assaulted in January of 2021, just a few weeks after returning to campus for the spring semester of my freshman year at Tulane University. I was at a frat party, and the next thing I knew, I woke up the next morning on a bean bag. I vaguely remember talking to a guy the night before. I had cuts on my face and hands, what I assume was my own blood was caked into the cracks of my shattered phone and my body ached.

A friend helped me go to Campus Health, who tried to immediately send me to the emergency room. It was an hours-long ordeal where I had to recount what little I could remember several times before I signed a waiver that said I was leaving against medical advice.

Given that I had been assaulted, all I wanted to do was call my mom. I didn’t want to sit in Campus Health and tell another person about what happened; I didn’t want to go to the hospital with no way of contacting anyone. My only option to contact her was to leave against medical advice and text her from my laptop.

We FaceTimed. It was silent when she first answered, and then I told her that I thought I had been sexually assaulted. She immediately sobbed; I still hadn’t.

We briefly spoke, and I lied to her. I told her that I was with friends at dinner and that some guy had just done something bad and random and violent. I couldn’t admit to her that I had seemingly put myself in a situation where some of the blame would inevitably fall on me.

The same friend who helped me go to Campus Health also accompanied me to the emergency room. The details of that aren’t important other than this: if you are the victim of sexual assault, they lock your file so that you’re untraceable. I understand it, and it’s a good rule. But, in January of 2021, New Orleans was still in the throes of COVID-19 and hospital visitors weren’t allowed. So my friend, who I am eternally grateful for, waited outside in the cold for me for hours.

I sat in the pediatric wing of the hospital – another safety measure I’m guessing – alone, confused and in pain. My nurse promised that she would bring my friend back. Hours went by. But, as she tried to check with the table at the front entrance, they told her there was no one by my name in the hospital. It took begging and pleading to have her with me.

That was my experience; or, at least what I’ve pieced together about it. My body remembers and still, to this day, I have small scars on my forehead, nose and hands.

It doesn’t matter how similar my experience is to Chanel Miller’s, but I know her stomach turned to rocks the same way mine did when she woke up that morning in a hospital bed. I know that she had the same feeling of being burdened with the feeling that something horrible and unnameable has happened to you, that agency has been stolen. I know for a fact that she has also experienced the worst of what comes after.

Another thing that you don’t learn until you’ve been assaulted is that the first moment of silence is the last moment you have as the only character in the narrative of the worst experience of your life. Every point from then on, there were others to consider or to have to share moments with.

I hadn’t thought much about my assault until recently. I put it in a cage and stashed it in a corner of my brain that never saw the light of day. I thought I was over it, that I had healed and that I had other things to be angrier about. But then, Tulane sent us “Know My Name” with cutesy stickers about believing victims and not a single trigger warning for the graphic details of the book.

I thought about it when I found out that several accused rapists were allowed to not be in just any leadership positions, but ones where they would be the first person that new students would meet on campus. They would be present for consent workshops. They would be someone freshmen were told to trust despite the university knowing the kind of person that they really are.

I thought about it when hundreds gathered at a demonstration I could only stay at for five minutes because of being retraumatized. I thought about it when Robin Forman, the Provost, sent out an email addressing this that said, essentially, “this is not who Tulane is”.

I thought about it when I was on assignment for the Tulane Hullabaloo the week before Halloween reviewing a concert. Outside of my full-time position as a victim, I’m a multitude of other things. For one, I’m a bassist. I jumped at the chance to review the Thundercat concert at the Orpheum Theatre.

I got there early and approached the pit, flashing the little sticker on my chest that said “press” like a badge of honor. In response, what I got was a comment about how the only reason that I was in the pit was because of my “pretty little dress.”

My press badge didn’t stop a drunk guy dressed up with his friends as members of the Blue Man Group from leaning over the barricade and hitting on me. The barricade was terrible at its job, it didn’t stop him when my lack of acknowledgment to his advances apparently was gravely upsetting. It didn’t keep him from leaning over my shoulder and getting into my face.

I never saw Thundercat perform.

As I said, Chanel Miller and I in no way have similar stories of our assault. But, she would understand how even the small instances of harassment are triggering when you feel like you’re trapped.

I’m sure she, and other victims, understand what it feels like to be fine for days, weeks and months after being assaulted only to suddenly realize that any man could be a bad one and that by the time you know, it’ll be because they’ve assaulted one. Victims of sexual assault know that recovery isn’t linear or sensical in any way. It doesn’t make sense, and it doesn’t have to.

Sometimes I lie about reading books. This one wasn’t a frivolous lie, though. Would I be a bad survivor of sexual assault if I didn’t read it? Would that make me somehow complacent? Is it even warranted that I’m having to question this; after all, Tulane sent students a book with graphic depictions of sexual assault with no thought to its impact.

After all, the administration of this school is the party involved that continuously fails victims of sexual assault. After all, I’m not the one who perpetrated the theft of my agency. So, I said that I had read it and thought every day since saying so that I should probably start reading it. And there’s nothing wrong with that.

This article has been corrected.

Resources are available for Tulane students who are victims of sexual violence. Contact Sexual Assault Peer Hotline and Education‘s 24/7 Peer Run Hotline at 504-654-9543 if you need help.

Tulane Emergency Medical Services can be reached at 504-865-5911. TEMS is a free, student-run service. In addition, Tulane University Police Department’s non-emergency Uptown number is 504-865-5381.

You can also reach out to Case Management and Victim Support Services at 504-314-2160 and they can offer support and help you file a report.

RAINN: Rape Abuse + Incest National Network provides resources that are LGBTQ+ inclusive and can be reached at 800-656-4673.

Read! Emails! Thoroughly! • Dec 3, 2021 at 2:43 pm

Thank you so much for your story; however, the Sexual Misconduct Survey was only delayed once because of COVID. It was not delayed yet again. If you read the email the provost sent: “The Sexual Misconduct Survey, which was previously delayed in spring 2021 due to the pandemic, will be administered as currently planned in spring 2022.”

Michal Rahabi • Dec 2, 2021 at 9:53 am

Thank you for your strength and courage, Liv— this school is lucky to have powerful women like you. Tulane must be held accountable for their complete irresponsibility and consideration for their students. Administration is highly concerned with its image— instead of helping students who have experienced sexual assault, they sent “Know My Name” as if it would solve the crisis on campus. I’ve had enough with the admins prioritization of Tulane’s rankings over the student body. How many times do we as students have to ask for Tulane to listen, to take action? Female students are concerned for their safety.