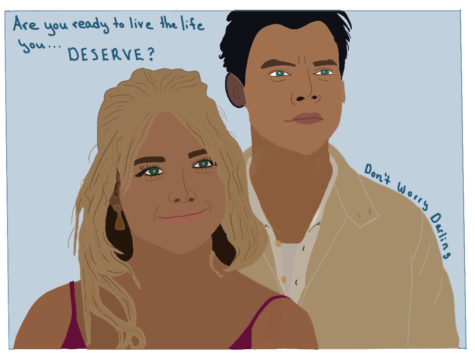

Don’t Worry Darling: Olivia Wilde’s almost-feminist second act

October 12, 2022

Olivia Wilde’s new thriller “Don’t Worry Darling” premiered in theaters late last month, amid a flurry of media drama. Wilde marketed “Don’t Worry Darling” as a distinctly-feminist psychothriller, “part of [her] ongoing project to examine the female experience from multiple angles.” I went to the Prytania last weekend to see how it held up.

The movie follows a couple, Alice and Jack, who live in a town called Victory. Jack, played by Harry Styles, has a vaguely-specified engineering job with the Victory Project, a top-secret government initiative run out of the deserts of California. All the men in Victory work for the Project, and all of their wives remain at home, in a permanent state of domesticity. It’s something out of Betty Friedan — Wilde called the film “the feminine mystique on acid.”

Alice, played by Florence Pugh, is Jack’s wife. She seems happy, despite living in a world that makes her entirely dependent on her husband. It is an experience of womanhood that we’ve seen before, in a context that feels far away. Victory is a version of suburbia that never really existed — though Wilde creates it in technicolor, as if drawing from a replicable past.

Alice’s distrust of the Project drives the first act of the movie. We see her become the trapped housewife, throwing fits, hallucinating and descending into bouts of paranoia. In the second act, her fears are vindicated, and we see a vague political commentary begin to take form.

Wilde struggles to integrate everything she is trying to say. “Don’t Worry Darling” is a mash-up of other popular cinema; “The Stepford Wives” is the obvious companion piece, “The Matrix” the secondary one. Jack evokes a slightly-more unkempt Travis from “Taxi Driver.” If we spent more time with him, he might remind us of Todd Phillips’ “Joker.”

The problem with “Don’t Worry Darling” is that similar films with similar commentaries have already been made. “The Stepford Wives” was subversive in the 70s, and in 1990, the simulated reality of “The Matrix” was interesting, cautionary and tangible. Masculine alienation, and its violent consequences, has been a theme in film since at least the 1930s. But in front of a modern audience, Wilde’s criticism feels limited, unable to say anything contemporary. We no longer live in a world where most women are trapped at home playing housewife. Since no screen time is given to the creation of Victory, the ‘alternate reality’ feels like a convenient plot device, a derivation of stories we’ve been told before.

“Don’t Worry Darling” had the opportunity to make a meaningful, modern critique of how we exercise control over women’s bodies. But Wilde is so enchanted with the beauty of the world she’s created, that we rarely leave it — we get no meaningful exposition of how Jack became radicalized, and no real interrogation of the fascist brotherhood controlling Alice and the other women. Lazily, the film tells us that incels are bad and traditional gender roles are limiting. No, duh.

Even “Don’t Worry Darling’s” superficial political statement is lost in the messaging around the film. Early on in the press cycle, Olivia Wilde called “Don’t Worry Darling” a film about “female pleasure,” describing the film’s sex scenes as a subversion of misogynistic notions of pleasure. This makes little sense within the context of Victory. Was one gratuitous oral sex scene supposed to negate the fact that Alice was lifeless, captive and tied up in her own home? That whatever pleasure she received was given without her consent? Here, it becomes hard to understand what statement Wilde is actually trying to make.

Misogyny is fashionable again, and in the midst of a growing men’s rights movement, the rise of Andrew Tate, the vilification of Amber Heard and the continued cultural backlash to “Me Too,” “Don’t Worry Darling” could have offered a meaningful critique of a culture that continues to exercise control over women’s lives and bodies. Instead, the film spends so much time critiquing structures that no longer exist, and has no time to make meaningful comments about the ones that still do. It’s no surprise that “Don’t Worry Darling” is unlikely to appear on the awards circuit — I was disappointed to see that much of the film’s early criticism was true.

Leave a Comment