Entangled with plantation history, Tulane removes iconic campus bell

Elana Bush | Photography Editor

An empty pedestal stands in front of McAlister Auditorium where the Victory Bell once stood.

March 5, 2020

According to tradition, it only rings twice a year: once for convocation and once for commencement.

Graduating seniors in the Class of 2020 were gearing up to hear the Victory Bell ring — until it was abruptly removed, leaving a barren stand in front of McAlister Auditorium.

The decision came after a discovery that the iconic campus symbol was originally a plantation bell. President Mike Fitts and Board of Tulane Chair Doug Hertz formally announced the news in an email last Thursday.

“As an academic institution, we believe it is important to find a way to use this bell to further our knowledge and understanding of slavery and pursue a more just society,” Fitts and Hertz wrote in the email.

Since its removal last week, more of the bell’s history has been uncovered, and students have shared their reactions.

Tulane University has removed its Victory Bell after learning that it originally came from a plantation where Africans were enslaved https://t.co/rMgMEItbv5

— CNN (@CNN) February 28, 2020

The Discovery

During the week of Feb. 17, a Tulane staff member expressed concern about the bell’s origins, according to Executive Director of Public Relations Mike Strecker. Strecker declined to identify the staff member.

“When this message was shared with President Fitts, he ordered an immediate review of university and state archives,” Strecker said.

After the administration was able to confirm the bell’s origins, it immediately made the choice to remove it.

The bell’s origin as a plantation bell, however, was recognized in a 1985-86 student handbook.

“One of the more obscure artifacts on the Tulane campus is the L.S.U. Victory Bell — a handsome old plantation bell cast in 1825,” the guidebook reads.

In 2004, a “Victory Bell Rededication” ceremony was held. The pamphlet for that event had fewer details about the bell’s origins.

“Although the history of the Victory Bell is somewhat a mystery, Tulanians today do know that it was cast in 1825 and that Richard W. Leche donated the Victory Bell to Tulane University,” the pamphlet states.

Origins of the Bell

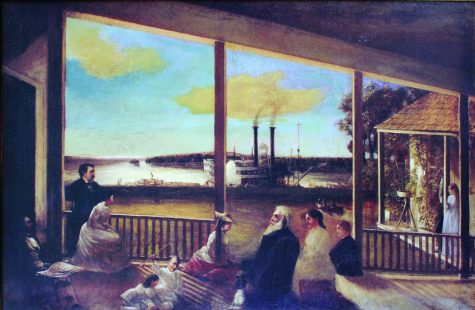

An image of a painting (ca. 1855) of the Columbia Plantation with the Mississippi River in the background. Pictured is the family of Valsin Marmillion. V. Marmillion is the white-haired man in center with wife. Marius Martin is far left with his family.

In 1751, the French King Louis XV gave the Marmillion family a property along the Mississippi river, making them the first family to live along Louisiana’s River Road. At this time, the land located about 40 miles west of Tulane’s campus would become the Columbia plantation.

Family member Valsin Marmillion owned the Columbia plantation and the enslaved African Americans who lived there. Norman Marmillion, distant relative of V. Marmillion and current president of the Laura Plantation Company, remembers V. Marmillion’s reputation through stories he has heard and read.

“Valsin Marmillion was known as a pretty cruel slave master,” N. Marmillion said.

Tulane’s Victory Bell was forged for V. Marmillion in 1825. For enslaved Africans who were not given their own pocket watches or clocks to check the time, the bell was used to communicate daily schedules.

“The ringing of the bell is very important, because the plantations are long, and the way you communicate on the plantations is with bells. You do that in the house with small bells and you do it outside the house with big bells,” N. Marmillion said. “The bell is a quivocal part of that plantation life and so it really has a significance that other bells won’t have.”

According to N. Marmillion, V. Marmillion had only daughters, one who married Marius Martin. When Martin died around 1888, the Columbia plantation was sold to the family who owns it today.

When the current family left, they took all their furniture with them, including Tulane’s Victory Bell, according to N. Marmillion.

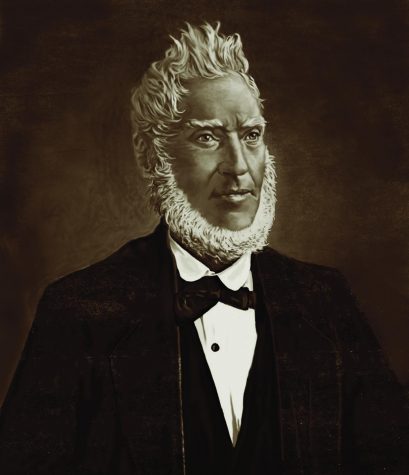

A 1870s portrait of Valsin Marmillion, retouched by Norman Marmillion.

From the collection of Dr. Olaf Schmidt, Washington University, St. Louis, MO, author of an upcoming book on the Marmillions.

“I think they took that bell because it was silver and it was quite valuable,” N. Marmillion said. “And all those things were being sold at a time when it was scarce and I think they wanted to keep whatever they had.”

The Martin family was also known in the 20th century for their strong support of former governor Huey Long. Martin family member Wade O. Martin Jr. later became the longest-serving Louisiana secretary of state and had close ties to former Louisiana governor Richard Leche.

Leche, a Tulane graduate, also graduated from Loyola Law School. He was one of two Louisiana governors to serve a prison sentence following corruption charges. After receiving a pardon from President Harry Truman, he continued to practice law in New Orleans.

Although there are no documents to confirm the bell’s whereabouts between V. Marmillion’s possession and Leche’s, N. Marmillion said he believes it was the Martins who gave Leche the bell.

“I don’t know whether it was the Sr. or the Jr. but that is always what I had thought because of the close connections politically with Richard Leche,” N. Marmillion said.

In 1960-61, Leche donated the bell to Tulane.

A Tulane Tradition

Upon its arrival at Tulane, the bell was rung for every athletic victory. As a rivalry with Louisiana State University formed in the 1930s, the bell came to be exclusively used for Green Wave victories against LSU.

In 2004, Tulane’s Undergraduate Student Government aimed to renew community appreciation for the bell in a rededication ceremony. During this ceremony, guidelines were set for the bell to be rung at the President’s Convocation and Commencement ceremonies. At the time, the bell had not been rung since 1998.

The guidelines set during the 2004 ceremony instructed three rings for any football victory and any postseason or conference tournament victory for any sport. Additionally, there were to be five rings following the President’s Convocation during orientation and at the start of the Wave Goodbye Commencement Weekend.

The #Tulane Victory Bell last night . S/O to @GreenWaveWBB on their win over UCF and to @GreenWaveWGolf at UCF. pic.twitter.com/2ZLksga7Di

— Parker Waters (@ParkerWaters) February 11, 2015

Most recently, the Victory Bell was dedicated to Tulane alumnus Bobby Boudreau, as the Bobby Boudreau’s Spirit Bell. As a part of the dedication, the bell was installed in front of McAlister Auditorium in 2011.

Boudreau graduated from Tulane as an undergraduate in 1951 and a law student in 1953. As an alumnus, Boudreau was a dedicated Green Wave fan. Winning the Volunteer Alumnus award in 2009, his loss was felt campus-wide upon his passing in 2010.

After the 2011 dedication, the bell continued to be a prominent symbol for Tulane spirit.

What will replace it?

The Victory Bell was also featured on photographs across campus, including a large image on a stairwell of the Lavin-Bernick Center for University Life. That image has already been replaced with an image of Crawfest, another Tulane tradition.

A photograph in a stairwell of the LBC that used to depict the Victory Bell has been replaced with an image of Crawfest.

The bell itself has been moved to storage as the presidential commission continues to investigate its exact history.

A special committee composed of students, faculty, alumni and staff will decide what will replace the bell’s spot in front of McAlister Auditorium.

“In doing so, we hope to establish a new tradition that truly represents a victory for all,” Fitts’ email read.

Marmillion thinks the bell could be a good addition to the Laura Plantation where he gives daily tours to educate visitors on the history of plantations along Louisiana’s River Road.

“It needs to go to a place where it can tell a story, that’s what it needs to do,” N. Marmillion said. “We would love to have it at Laura because it would be personal in that sense. I could say, ‘This is my family’s bell and this is what happened here.’ I think that would make a difference for people when they heard a story that is personal like that.”

Campus-wide efforts

The removal of the Victory Bell is a small part of efforts around campus aimed at dismantling racist history entrenched in the physical spaces of campus.

In fall of 2017, USG passed a resolution to rename Hebert Hall. Tulane alumnus F. Edward Hebert opposed the desegregation of schools and was a supporter of the “war against Civil rights.” Hebert Hall’s title has not changed since the legislation was passed, however.

All of which is laughable at a university named Tulane.

— (((Michael Jacobs))) (@ChipJake) November 29, 2017

Following these efforts, co-author of the legislation Sonali Chadha felt skeptical of the motivation for taking down the bell.

“I — as well as a lot of students — believe this information came to the President’s office and they were worried it’s publicity would harm the image of the school,” Chadha said.

Following efforts to change namesakes and dedications in 2017, a Campus Recognition Committee was added as a sub-committee of the President’s Commission on Race and Tulane Values. According to its website, “this sub-committee has engaged the university community to identify and recommend a diverse group of individuals for special recognition in various ways on our campuses.”

Last November, the committee’s Trailblazer Initiative led to the renaming of what was formerly Willow Residence Hall. The building was renamed Decou-Labat Residences after Dr. Diedre Dumas Labat and Reynold T. Decou Sr., who were the first African-Americans to earn undergraduate degrees from Tulane.

Sophomore Maya Black was glad to see the bell removed but wondered why it hadn’t been removed before last Thursday.

“I thought it was fair, I didn’t think that the bell should continue to stay, especially if it’s not something that we as a school say that we stand for,” Black said. “I was a little surprised and distrusting that it hadn’t been removed before because I feel like it’s pretty unlikely that Tulane didn’t catch that before it erected that bell in the first place.”

Some students are looking to Tulane’s peer institutions as models for what Tulane should be doing to address its racist past.

“Tulane is continuously doing the least amount of work possible to then go and applaud their work as if they are some radical institution,” Chadha said. “The reality is all of our peer institutions are doing way more work in this realm to reach some sort of equity.”

The National Movement

In the past several years, universities around the world have made similar decisions to Tulane’s removal of the bell in efforts to address racist histories.

In May of 2019, a college at the University of Cambridge similarly removed a bell they suspected to be linked to slavery. In light of their discovery, the University of Cambridge began a two-year study on how their institution benefited from the slave trade.

Similarly in 2017, Georgetown renamed two of its buildings that honored the university’s presidents who had overseen the sale of 272 slaves. They also gave preferred admission to descendants of those slaves.

George Washington University student body voted Thursday to ‘remove and replace’ its mascot, the George the Colonial, because George Washington owned slaves.

California University Dumps 'Offensive' Mascot – Big League Politics https://t.co/csErtUVhla

— Buddahfan (@Buddahfan) April 28, 2019

Rutgers University and Princeton University also renamed two buildings on their campuses around the same time.

USG President Joseph Sotile said he was not surprised to find out that a prominent symbol on campus was linked to slavery.

“While I appreciate the expediency in taking down the bell and the transparency to the student body with the process, this is a stark reminder that Tulane has a long way to go in terms of reckoning with our past and giving all students, especially black students, the necessary support to let them know that they belong here,” Sotile said.

Leave a Comment