OPINION | Tulane film department requires modernization

March 24, 2021

Enrolling in a film class initially feels kind of like getting away with something, sort of how being a Moviepass subscriber in 2018 felt — excited to watch a bunch of movies, but still slightly suspicious of how sweet the deal really is. Everyone imagines that while their friends will be sweating over essays and exams, they will be reclining in their beds watching explosions, sex scenes or Adam Sandler, all for academic credit.

Sadly, this fantasy is short-lived. Mid-way through the course, students will often find that their idea of what makes an exciting movie has been warped. The humble presence of color and audio in the assigned viewings morphs into a special treat for which to be thankful. In reality, this is just a normal, albeit sad, reaction for anyone experiencing a variant of Stockholm syndrome wherein their captors are boring movies. This should not be the norm.

If the purpose of film analysis classes were just to teach the history of motion pictures from cave paintings to “Avengers: Endgame,” then there would be no contention that paragons like “Cleo from 5 to 7” or “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari” are important to talk about. Both certainly represent important benchmarks in the development of cinema, among others. But, this is not the case. Film classes focus on elements of production as well — the camera techniques and style that archetypal film-class films are lauded for are abundant in more culturally-relevant works. Exposure to films that reflect the issues and events of modern life is a crucial component of film analysis that is inexplicably overlooked in favor of prioritizing archaic cinematography.

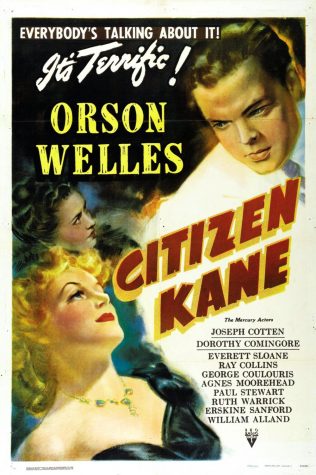

“Citizen Kane” is thought to be one of the greatest films ever made because it exemplifies mastery of the deep focus — a visual effect where every object in the field of view appears clear to the viewer no matter how distant it is from the lens. But what good is the educational value of this mastery if the students in the class are too daunted by the pallid scenes they know are forthcoming to ever press play? Of course, part of being a good student of any subject is being diligent and resolute, but leaving up extra barriers is not doing anyone any favors.

“Harry Potter and The Prisoner Of Azkaban,” as an alternative, uses the same deep focus camera technique but has a fraction of the think-pieces written about it. If “Harry Potter” were substituted for “Citizen Kane,” for example, students would be more compelled to watch the required viewing and thus would be more likely to learn the curriculum. And, those who have not yet been privy to “Harry Potter” will finally have that comparatively larger gap in their cultural knowledge somewhat mended. Professors should reconsider how important a film’s critical reputation actually is when trying to connect with a cohort of young people.

It is also in the best interest of the larger film community to ask students to challenge the orthodoxy that exists in cinema by giving them the tools and gall to decide for themselves what makes a film great. “Citizen Kane,” possibly the most commonly examined film across college campuses, was not fully appreciated until long after its time. Only when Andre Bazin rewatched it and paid closer attention to its merits did it become what it is today. This begs the question of how many contemporary movies are being ignored because incoming film students think there is such a thing as an absolute in a world of subjectivity.

It is annoying to be told the films shown in film classes are “great” and then not enjoy any of them. Students likely finish these courses feeling as though their “cultural palate” is unrefined when it might just be rightly expecting more. Shrugged shoulders at the finale of many allegedly “great” films are nothing to feel guilty about. What was remarkable 100 years ago is not necessarily as important now.

Mike Maloney • Mar 29, 2021 at 10:59 pm

I love the reference to Adam Sandler