OPINION | Jerusalem Declaration on Antisemitism presents improvement, not end goal

April 8, 2021

In May 2016, the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance, an intergovernmental organization headquartered in Berlin that is dedicated to advance and promote robust Holocaust education, touted its Working Definition of Antisemitism. The definition states that “antisemitism is a certain perception of Jews, which may be expressed as hatred toward Jews. Rhetorical and physical manifestations of anti-Semitism are directed toward Jewish or non-Jewish individuals and/or their property, toward Jewish community institutions and religious facilities.” Attached to this definition were several examples, ranging from application of tropes of Jewish people to certain forms of commentary on Israel.

Although this definition was first publicly discussed in 2016, in recent years there has been a large push by university groups, political coalitions and even the Israeli government to pressure different institutions to adopt this definition. Despite the definition being a “working” one and concerns over its implications for free speech from various Jewish, Palestinian and other actors, including its lead legislator, the definition continues to be adopted, even by the U.S. government.

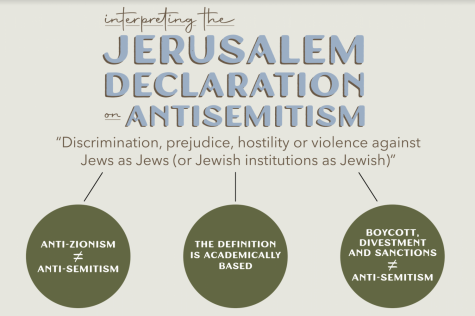

Citing the IHRA definition as a reason for its creation, the 200+ scholars who drafted the Jerusalem Declaration on Antisemitism sought to strengthen the fight against antisemitism while protecting free speech regarding Israel/Palestine when they presented it last month. The declaration defines anti-Semitism as “discrimination, prejudice, hostility or violence against Jews as Jews (or Jewish institutions as Jewish).” Attached to the definition are guidelines, both generally and specifically with respect to Israel/Palestine.

These two definitions differ tremendously. IHRA’s definition will not allow any racial critiques of Israel’s founding, while the JDA definition lists the boycott, divestment, and sanctions movement as legitimate, full stop. However, even JDA’s definition falls short. First, as a response to the IHRA definition, it is incomplete as a whole definition and narrow in scope. A definition that positions itself against an existing one, as opposed to one that is simply dedicated to encapsulating a certain construct, will ultimately fall short. Additionally, despite the heavy emphasis on Israel/Palestine politics in the definition, no Palestinians are undersigned.

The JDA definition is, in my mind, a step in the right direction for contemporary discussions of anti-Semitism and a useful tool in dealing with its manifestations. However, codification of systems of oppression is not a necessary nor always effective manner of combating them. Oppression may fluctuate over time, and definitions may seem dated over time.

Neither the IHRA nor JDA definition has provided a compelling argument as to why anti-Semitism needs to be spelled out in order to be combated, especially in the academic and legally binding contexts in which these definitions were forged. Definitions such as these are rigid and would presumably act as a “cheat sheet” for legislative or legal policy changes, thus limiting critical thinking on anti-Semitism as it emerges or dies out, and assuming a set of common experiences amongst global Jewry, a harmful monolithic misconception. These definitions may be rooted in or promote themselves unhelpful, misleading paradigms about oppression, such as the IHRA’s description of anti-Semitism as a “scourge,” which infects a society, as opposed to critically analyzing anti-Semitism’s source.

While potentially a useful template, codification of anti-Semitism has been shown to often lead into a hyperfixation on tropes that promote anti-Semitic rhetoric as opposed to material concerns, such as Jewish safety. Of course, harmful ideas and stereotypes may snowball into violence or harmful police, but modern-day Jews have better things to worry about than if “cabal” is an anti-Semitic term. Not least of all, the adoption of these definitions has implications for policy, and one that leans towards the criminalization of perceived anti-Semitism. A carceral perspective on ending anti-Semitism will not accomplish safety for Jews and may often lead to the targeting of other groups. In summation, though definitions of anti-Semitism are not made equal, treating these as anything other than general guidelines to critically engage and grapple with is an erroneous way to go.

Jimothy • May 27, 2021 at 10:50 pm

Jimothy

Julie • May 3, 2021 at 9:48 pm

Interesting that the “intersections” crew feels threatened by accusations of anti-semitism. I wholeheartedly agree with jewish!, above, who writes, “glad that y’all are giving up the pretense and just being blatantly antisemitic now.” I do disagree with Joshua Crommie’s assertion that the Hullabaloo should not be printing this. Censorship is wrong, and in this case would have allowed the “Intersections” staff to deny their anti-semitism instead of laying it on display for all to see, as they have in this article.

Jaap • May 3, 2021 at 11:34 am

Good article!

Joshua Crommie • Apr 21, 2021 at 3:09 am

Ok that is just franckly insane, non-Jews have absolutely no place in deciding a definition on Anti-Semetism. Regardless if it touches on Israel/Palestine it is Jews who experience anti-semtism especially in regards to Israel/Palestine who should define it. The fact that it was even implied that non-Jews should have an input in defining prejudice towards Jews is anti-semetic and something a university should not be printing.

jewish! • Apr 11, 2021 at 10:11 am

glad that y’all are giving up the pretense and just being blatantly antisemitic now

Fred Skolnik • Apr 9, 2021 at 9:11 am

One would naturally expect a declaration on antisemitism to have been produced by people who have spent their lives fighting it. This one has been produced by people who have spent their lives attacking the State of Israel, often in the most violent and malicious language imaginable, and it is in fact not very hard to see that its sole purpose is to legitimize these attacks by immunizing them to accusations of antisemitism. In other words, their real concern is not the victims of antisemitism but themselves.

As for antisemitism as it is expressed in attacks on Israel (and criticism of Israel as such is not necessarily an expression of antisemitism), the giveaway is always the vehemence of the language (wild and irresponsible accusations of Nazism, fascism, genocide, war crimes, racism, apartheid and a general tone of vindictive hostility), language which few of these great humanists would ever think to use with reference to truly genocidal nations and some of the greatest violators of human rights on the face of the earth (Sudan, Rwanda, Syria, Iran, Russia, China, etc.). When uninformed people come down very strongly on one side or the other of a regional conflict concerning countries they’ve never seen where people speak languages they don’t understand, popping up everywhere with their virulent “takes” on the situation, it also raises very natural suspicions. To take sides in the Arab-Israel conflict when one is totally unequipped to verify or evaluate what one finds in biased second- and third-hand English-language sources is certainly another giveaway. However, we don’t really need new declarations and definitions. All we need is half a brain and a little objectivity. It really isn’t that hard to spot a Jew hater. He always gives himself away. He can’t help himself.

One of the aims of the Declaration is of course to sanitize the BDS movement. Is the BDS movement antisemitic? No more than the previous Arab boycott of Israel that pretty much petered out in the 1990s, that is, it is one more anti-Israel measure initiated by Arabs and/or Palestinians to bring about the disappearance of the State of Israel, and even a relatively mild one compared to their barbaric acts of blowing up Israeli women and children in buses and restaurants to achieve the same ultimate end. This is not the question then. The question is whether the movement, along with countless I Hate Israel websites, attracts non-Arab supporters who are antisemites. Surely it does, for haters of Jews are bound to be haters of Israel too. How many? What percentage? Maybe a great many. Maybe most. How can you tell who is and who isn’t? Once again, by all the obvious signs, by the language, by the vehemence, by the venom.

Fred Skolnik • Apr 8, 2021 at 1:29 am

One would naturally expect a declaration on antisemitism to have been produced by people who have spent their lives fighting it. This one has been produced by people who have spent their lives attacking the State of Israel, often in the most violent and malicious language imaginable, and it is in fact not very hard to see that its sole purpose is to legitimize these attacks by immunizing them to accusations of antisemitism. In other words, their real concern is not the victims of antisemitism but themselves.

As for antisemitism as it is expressed in attacks on Israel (and criticism of Israel as such is not necessarily an expression of antisemitism), the giveaway is always the vehemence of the language (wild and irresponsible accusations of Nazism, fascism, genocide, war crimes, racism, apartheid and a general tone of vindictive hostility), language which few of these great humanists would ever think to use with reference to truly genocidal nations and some of the greatest violators of human rights on the face of the earth (Sudan, Rwanda, Syria, Iran, Russia, China, etc.). When uninformed people come down very strongly on one side or the other of a regional conflict concerning countries they’ve never seen where people speak languages they don’t understand, popping up everywhere with their virulent “takes” on the situation, it also raises very natural suspicions. To take sides in the Arab-Israel conflict when one is totally unequipped to verify or evaluate what one finds in biased second- and third-hand English-language sources is certainly another giveaway. However, we don’t really need new declarations and definitions. All we need is half a brain and a little objectivity. It really isn’t that hard to spot a Jew hater. He always gives himself away, He can’t help himself.

One of the aims of the Declaration is of course to sanitize the BDS movement. Is the BDS movement antisemitic? No more than the previous Arab boycott of Israel that pretty much petered out in the 1990s, that is, it is one more anti-Israel measure initiated by Arabs and/or Palestinians to bring about the disappearance of the State of Israel, and even a relatively mild one compared to their barbaric acts of blowing up Israeli women and children in buses and restaurants to achieve the same ultimate end. This is not the question then. The question is whether the movement, along with countless I Hate Israel websites, attracts non-Arab supporters who are antisemites. Surely it does, for haters of Jews are bound to be haters of Israel too. How many? What percentage? Maybe a great many. Maybe most. How can you tell who is and who isn’t? Once again, by all the obvious signs, by the language, by the vehemence, by the venom.