‘You are not alone’: Tulane sexual assault survivor speaks up

March 16, 2022

Content Warning: The following article contains subject matter pertaining to sexual violence.

On a Sunday night, in the late winter of 1984, 17-year-old Angela Lore found herself at a daiquiri shop on Bourbon Street. She met eyes with a handsome stranger wearing a Tulane University Athletics sweatshirt.

Soon, the bar became crowded and Bourbon Street filled with pedestrians. “Mr. Handsome” offered to drive her home. She knew she could trust him. He was a Tulane student.

As “Mr. Handsome” led Lore out of the bar and onto Bourbon Street, an older girl grabbed her arm and warned her not to leave with him. After that, everything went dark.

Lore awoke to something painful, naked from the waist down. A man, who was not “Mr. Handsome,” was assaulting her. Another man stood half dressed in the corner, and others were scattered around the room watching.

It all ended at 3 a.m., five hours past Lore’s curfew.

“Mr. Handsome” and two friends drove Lore to her home in North Kenner. They made her sit in the backseat. Her father was waiting outside when they arrived. Lore was missing a shoe.

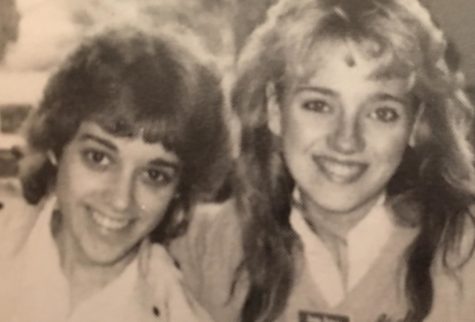

She walked into class late the next day. Lore remembers her best friend Donell asking if she was okay. Donell mouthed “they were naked?”

They never spoke about it again, not until 2018.

34-and-a-half years later, Lore could no longer be silent. In September 2018, Lore’s husband sat watching TV as Christine Blasey Ford gave her testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee, during which she waged allegations of sexual assault against now Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh.

Lore washed their dishes from dinner as Ford’s voice played in the background, drowning out the newscast until she heard the words “train rapes.”

“Suddenly, there was this 17-year-old, buried deep inside me for 35 years, screaming to be heard,” Lore said.

“With wet, soapy hands and a dish towel strewn over my shoulder, I charged toward the TV, grabbing the remote, pressing the off button with the force of a lifetime of built-up rage. And then, I said it. ‘That’s what happened to me.’”

On Oct. 4, 2018, Lore called the Tulane University Police Department to report her sexual assault, more than three decades after the fact.

“I felt their campus should know what happened to a 17-year-old high school student, who was taken to one of their residence halls, defiled, violated and without her knowledge, albeit 34 years earlier,” she said.

Lore says she appreciated the compassion and attentiveness of the TUPD detective who spoke with her, but more importantly, she says, made her feel believed.

Lore took her case to the New Orleans Police Department two days later. There, she said, the officer was less attentive. She recalls almost hanging up the phone, consumed by regret.

“I mentioned to him, ‘I’m not just part of the #MeToo movement,’ said Lore. “That statement felt more appropriate than ironic.”

The NOPD officer asked if she knew the name of her perpetrators. At the time, Lore could not recall “Mr. Handsome’s” or any of the other men’s identities.

According to Lore, NOPD notified her that her case was classified as simple rape.

“There is nothing simple about what was done to me,” Lore said.

Lore also hired a private investigator to help her find the men responsible for her assault and attempt to get justice. She did her own detective work as well, scouring the web, yearbooks and social media.

While searching the internet for leads in March 2019, Lore stumbled upon — and ordered — a 1984 Tulane football program on eBay. When it arrived in the mail, she said, she found “Mr. Handsome.”

“This 35-year-old picture is now my smoking gun.”

On April 11, 2019, Lore sent “Mr. Handsome” a text with a picture from her 1984 high school yearbook. He called her 40 minutes later.

According to Lore, “Mr. Handsome” admitted to the assault and named two of the other perpetrators during their phone conversation and over text. He denied doing so when contacted by NOPD.

Lore located the other accused men and sent each of them victim impact statements.

Lore’s charge conference to decide whether or not her case would move forward in the Louisiana court system was scheduled for June 31, 2019.

“Me, being resourceful and a bit impetuous, I decided to call the Supreme Court downtown and asked for the librarian,” Lore said. “On a hunch that she could help me, I asked for the rape statue from 1984.”

Lore then learned that the statute of limitations had run out on her case. It was not until 1985, just a few months after her assault, that Louisiana redefined aggravated rape adding a clause that included those committed by two or more perpetrators.

Unlike simple rape, aggravated rape has no statute of limitations.

Upon learning this, Lore’s charge conference was canceled. Lore’s investigative work, however, led to her case being “cleared by exceptional means.”

“Without that identification by me, the text confession, my case may have been labeled unfounded. Rather, invalidated,” she said.

Although Lore will never know traditional justice, she is now a voice for survivors and an outspoken advocate.

“Like many survivors of sexual violence, it was the voices of others that gave me strength and hope as I came forward,” Lore said.

When she began crisis counseling with Sexual Trauma Awareness and Response, Lore said the organization’s advocates validated her emotions and listened to her. Lore recalls many days where she found it hard to breathe and that she did not imagine how exposed she would feel after disclosing.

Now, she says, “being by another survivor’s side, throughout their crisis, even just to sit quietly, lends itself to my own journey of healing.”

Alix Tarnowsky, vice president of survivor services at STAR, was one of the first people Lore worked with at the organization and has been a longtime member of Lore’s support system.

“Doing this work can be difficult as there are often barriers that we encounter that are demoralizing or make us feel like we’re fighting a losing battle,” Tarnowsky said. “Being able to work alongside Angela reminds me that there is a reason to keep fighting for and with survivors.”

After coming forward, Lore dove headfirst into advocacy. She was STAR’s Champion of Change in 2019 and a keynote speaker at STAR’s fundraising event honoring those who have shattered the silence of abuse. In 2021, Lore became a member of RAINN’s Speakers Bureau and recently appeared on Katie Koestner’s podcast “Dear Katie.” Koestner is the executive director of the Take Back The Night Foundation.

In the future, Lore hopes to become a volunteer through STAR and help assist sexual violence survivors of the Northshore.

She is set to speak at the University of Louisiana at Monroe in April for Sexual Assault Awareness Month and will share her testimony at Shreveport’s Men for Change event that same month.

“My new mantra to myself is ‘stand up and speak out’ and the only way to do that is make those calls to agencies in need, such as the Hope House in Covington, Louisiana.”

Lore’s husband, Brad Lore, has been by her side since her initial disclosure and is now an adamant supporter of her advocacy efforts.

“Watching her step outside of her comfort zone in the face of adversity has been truly inspirational for me … I am continually amazed at her ability to speak so eloquently about such a painful topic,” he said.

Coming forward and processing her trauma, Lore says, has allowed her to better understand the root cause of personal difficulties.

“It was three weeks after starting counseling through STAR as well as private therapy, where I learned my life-long insomnia and subsequent Nyquil/Benadryl abuse was part of PTSD; along with anxiety, depression, phobias and previous thoughts of ending my life, which required medication.”

Despite grappling with her identity as a victim and survivor, members of Lore’s support system say her strength and determination are ever present.

“It can be scary and difficult to share your experience with a stranger, to say ‘this happened to me’ and not know what their response will be,” Tarnowsky said. “Angela consistently shows up as her true, authentic self and when she [receives] disappointing news or information, she [doesn’t] let that stop her.”

For Lore, telling her story is integral to her recovery and advocacy. She says empowering others to find their voices is transformative.

“As survivors, our lives become mired down by our silence and the agony of injustice,” Lore said. “Knowing the startling statistics of those that never report along with difficulties in prosecuting those that do, evokes a passion within me to speak out loud in the hopes [that] those still suffering in silence will hear that it’s okay to talk about.”

Expanding on this, Tarnowsky said, “It can be easy to brush aside a survivor’s story when we don’t have a name or a face to attach to it. When survivors like Angela stand up and share their story, it inspires others to share theirs, and reminds our community what is at stake when we don’t hold offenders accountable.”

Lore’s story is most certainly not the only of its kind at Tulane, where, in 2017, 33% of women, 15% of men and 29% of gender non-conforming students reported being sexually assaulted since they enrolled at the university.

As one of many victims in Tulane’s history, Lore wants to see real change and more compassion from administrators.

“My hopes for Tulane or any university would be to acknowledge the ongoing and destructive sexual violence proliferating their campuses,” said Lore. “Victims of all gender-based aggression often suffer irreversible damage; especially the ones who are victim-blamed or not believed at all.”

Regardless of her advocacy’s outcome, Lore will continue to share her story. For victims at Tulane, Lore says “you are not alone.”

“My life is a true testament to unresolved trauma and the consequences of sexual violence,” said Lore. “This year, I’m realizing that I can overcome despair and hopelessness of both past and present.”

Resources are available for Tulane students who are victims of sexual violence. Contact Sexual Assault Peer Hotline and Education‘s 24/7 Peer Run Hotline at 504-654-9543 if you need help.

Tulane Emergency Medical Services can be reached at 504-865-5911. TEMS is a free, student-run service. In addition, Tulane University Police Department’s non-emergency Uptown number is 504-865-5381.

You can also reach out to Case Management and Victim Support Services at 504-314-2160 and they can offer support and help you file a report.

RAINN: Rape Abuse + Incest National Network provides resources that are LGBTQ+ inclusive and can be reached at 800-656-4673.

Leave a Comment