Letter to the Editor: New Orleans’ illustrious history deserves unvarnished retelling

February 21, 2019

While in New Orleans last year for an accepted students weekend at Tulane, my dad and I decided to kill an afternoon by driving outside of the city to Oak Alley Plantation. The plantation advertised itself as a lovely Greek revival mansion, and as visitors, we looked forward to seeing it. We would soon learn that enjoying many of New Orleans’ tourist attractions isn’t always as simple as it seems.

When we got to Oak Alley, we marvelled at the massive oaks lining the front walkway and the beautiful antiques inside, and we indulged in what it might be like to live in such a stylish and elegant house. We stood on the balcony, felt the breeze off the river rustle the leaves of the oak branches around us, and felt elated – at one with the allure of the South.

But when we got home, my mom and brother were horrified. Despite attempts to convince them otherwise, they berated us for buying into the charming facade of a dark and immoral story. To them, it was as if any appreciation of the house free of the burdens of slavery was obscene. It was as if we visited a concentration camp and complimented the landscaping.

In many ways, they aren’t wrong. And, to be fair, my dad and I spent a good amount of time also touring the former slave quarters and learning about the plantation’s specific slave history. Yet many people don’t, and even doing so doesn’t fully excuse deriving pleasure from a culture of oppression.

I’m a freshman at Tulane now — a history major — and like all newcomers to the city, I’m eager to explore New Orleans. Part of college’s allure for any high schooler is the opportunity to experience a new place on your own. For students interested in Tulane, that allure is magnified ten times over. And the school isn’t naive either, as a considerable part of its marketing capitalizes on New Orleans’ appeal.

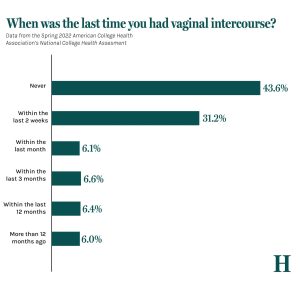

But the university attracts students from around the country and world (73.99 percent of undergrads are white, over 50 percent from outside the South), and a face-value tuition of nearly $75,000 ensures that many students come from privileged backgrounds. Statistics like those certainly don’t match those of the rest of the city.

Though the school undeniably has a strong connection with its surroundings, I’ve repeatedly encountered locals who describe New Orleans as a four-year playground for Tulanians before they head elsewhere. When NOLA seems like a temporary home, and a little foreign beyond the confines of campus, it’s easy to see how students may engage with it carelessly, or at least without taking the time to understand all sides of history.

This isn’t a critique of New Orleans and its residents. On the contrary, what I’ve observed of the city since becoming a resident myself has blown me away. There are things like Hurricane Katrina and the Saints that seem to unite New Orleanians well beyond their differences — to the point where neighborhood streets feel like a block party for a large extended family. If there’s a problem, it lies in New Orleans’ lifeblood: its tourism industry. In order to market their attractions successfully, cities and organizations seem to believe they have no choice but to appeal to the more idealistic side of history to be enticing.

For cities like New Orleans, that usually means peddling the allure of a genteel south. And New Orleans does it fantastically well — taking the streetcar, travelling along the Mississippi in a historic steamboat and listening to jazz amid its seemingly untouched facade is really an unparalleled experience. But underneath NOLA’s distracting colors are several revisionist histories, or at least overlooked truths.

Take Voodoo — originating from West African religions and some Catholicism, it preserved indigenous beliefs and strengthened slave communities in the wake of oppression. But now the term is often a catch all for “haunted” New Orleans. Countless French Quarter tour companies and Voodoo shops capitalize on tourists and their souvenir needs.

Perhaps the most obvious example is Voodoo Fest — since 2013, the event is produced by Live Nation Entertainment, based out of Los Angeles. This popular music festival differs little from those it brings to other cities, making “Voodoo” merely a personalization tool for an impersonal commodity. That shows just how far accurate history is often detached from marketable tourism.

Some might argue that the widespread use of the term “Voodoo” keeps Voodoo itself alive and celebrates the tradition rather than exploiting it. They might also argue that plantation houses preserve history and should be visited simply to learn about the past. Elements of that are true, but not when these artifacts of history are engaged with thoughtlessly. As a Tulane student and a newcomer to New Orleans, what I’m learning is that the amazing history here is certainly worth exploring — it just has to be sampled mindfully.

Leave a Comment