Why Tulane left the SEC

September 23, 2022

On Dec. 8, 1932, Tulane University, along with 12 other schools from the 28 institution Southern Conference met in Knoxville, Tennessee to create a new athletic conference. Featuring teams such as in-state rival LSU and other football powerhouses including Alabama, Florida and Georgia, the new Southeastern Conference sought to be the most elite and powerful in all of college sports and would change the landscape of the sport forever.

On New Year’s Day earlier that year, the Olive and Blue had finished their season at the pinnacle of college football in “The Granddaddy of them All,” the Rose Bowl, narrowly falling to and having their national championship hopes crushed by the University of Southern California Trojans.

But it did not take long for Tulane to make an impact in their new conference. In the conference’s second season, the 1934 Green Wave team was crowned SEC co-champions in football, along with Alabama, after finishing 10-1 overall and a perfect 8-0 in the SEC. That same year, Tulane won the first-ever Sugar Bowl in Tulane Stadium, a feat that would take LSU 24 more years to accomplish. Tulane then won the SEC again in 1939, this time tying Tennessee and Georgia Tech.

Other major accomplishments by Tulane in the SEC include Wave baseball player Stephen Martin Sr. becoming the first Black athlete to compete for any of the conference’s teams at any level in 1965, and Tulane men’s tennis won a staggering 18 SEC championships during its 34 years in the conference.

Tulane’s football glory lasted until its 1949 campaign. The Green Wave had been selected by The Sporting News as its pre-season national champion and boasted the highest average attendance in the SEC the year before at 37,058 fans per game.

Looking to win their 11th consecutive game, No. 4-ranked Tulane traveled to face the No. 1-ranked Notre Dame Fighting Irish who had not lost in 31 consecutive games. The winner of the game would be the favorite to win the season’s national championship and legendary Notre Dame coach Frank Leahy viewed the Wave as a true threat to his team. To the surprise of many, Tulane allowed the Irish to score four touchdowns on their first four drives and ultimately lost 46-7.

Despite ending their season as undisputed SEC champions for the first time, the brutal loss to Notre Dame and a season finale loss to LSU cost the Wave a Sugar Bowl berth and Tulane football has been out of national spotlight ever since.

In this week's Looking Back series, we examine the 1949 @SEC Champion Green Wave.

The 1949 squad ranked as high as No. 4 in the national polls.

Full Story: https://t.co/MKQhnnwVcd#RollWave pic.twitter.com/R05V3eB5Tw

— Tulane Football (@GreenWaveFB) May 21, 2020

Following the 1949 season, several decisions led to the downfall of Tulane football. At the time, Tulane had about 100 athletes on scholarship — a typical number for an SEC program — and most football players studied physical education, which required no academic major and allowed 50 hours of P.E. coursework.

Tulane’s downward trajectory started when then-president Rufus Harris scaled back the university’s intercollegiate athletics. In 1951, Harris reduced the number of football scholarships to 75, cut the salaries of staff and coaches and limited its coaches’ ability to scout talent. Tulane also reclassified physical education as a minor, and athletes were required to follow tracks leading to bachelor’s degrees.

The new parameters set by Harris proved to be problematic for the Wave’s SEC prowess. During the 14-year de-emphasis period from 1952 to 1965, Tulane football went 37-95-8 overall, averaging less than three wins per season. The program had just two winning seasons and cycled through four coaches during that time. In SEC play, Tulane posted a dismal 16-71-5 record and the university’s scholarship restrictions were so tough that there were just 38 players on the varsity football roster one season.

In the late 1950s, many started to question Tulane’s future in the SEC and in September 1963, the university announced it would stay in the conference while “continuing to study the effects of changes that might occur both within and outside of the conference.”

There was talk about Tulane leaving the SEC for a “Southern Ivy League,” to be called the Magnolia Conference and would include schools such as Rice, SMU and Duke; however, each of the others stayed in its conference.

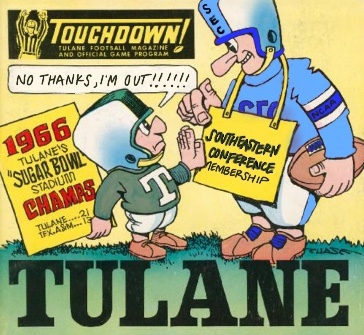

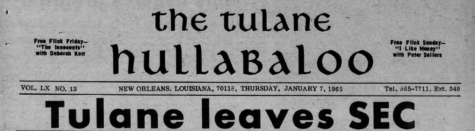

De-emphasis and its succeeding cutbacks led to the most consequential decision in the school’s athletic history — its decision to leave the conference it once chartered. After over a year of consideration, on December 31, 1964 then-Tulane president and SEC Vice President Herbert E. Longenecker announced that Tulane would leave the SEC in June 1966.

“Many people expected this, some were disheartened by it, and others just thought Tulane was ‘saving face’ before being expelled from the conference next Jan. 12th.,” wrote Hullabaloo sports editor Stuart Ghertner in January 1965.

Despite calling the Green Wave’s time in the league “pleasant,” President Longenecker said Tulane was withdrawing from the conference to play a more national schedule.

“Tulane University has changed in the past two decades from an institution, drawing its students mostly from the area to one attracting students from all states of the nation. The purposes of the university, for this reason, will be better served by scheduling intersectional games. We also wish to have freedom to design schedules that will improve our competitive position and avoid the overload situation Tulane has experienced in recent years,” said Longenecker.

Longenecker was not wrong about Tulane’s position as a prestigious national university and the fact that its football program suffered tremendously in the SEC over its final 14 seasons. Tulane’s decision to leave came because administrators decided the school was no longer an athletic powerhouse. They could not compete in the SEC any longer, and if you cannot win, you cannot recruit, and if you cannot recruit, you cannot make money. In essence, Tulane’s athletic policy could not keep up with the university’s academic ambitions, and while the decision revolved around the football program, it would affect all varsity sports at Tulane.

When announcing Tulane’s departure from the SEC, President Longenecker said that the university had no intention to further de-emphasize football or any other teams, and that the cost of football was not a factor in leaving the SEC.

In the 1964 season, Tulane athletics spent $260,000 in tuition alone for football scholarships, not including the cost of housing and meals, and it was reported that the university was losing a half million dollars per year on the sport. However, money is exactly why the Green Wave should have never left the SEC.

On November 20, 1965, the Green Wave played their final SEC football game in Baton Rouge and were embarrassed by LSU losing 62-0. “Tulane’s route out of the Southeastern Conference Saturday night led through the valley of ineptitude and LSU couldn’t have scored any easier or any oftener in the first half if it had been playing the Tulane Stadium ground crew,” Pie Dufour of the Times-Picayune said following the contest.

After leaving the SEC, Tulane competed as an independent and faced teams such as Notre Dame and Stanford and kept its rivalry with LSU. Tulane saw success soon after leaving, ending their 10-year drought without a winning season in its first year outside of the league, followed by three more over the next seven years. The average attendance at Tulane Stadium shot up to 38,844 that season, including a crowd of 82,567 for the LSU game. However, Tulane’s success outside of the SEC would not last long.

As a consequence of its departure from the SEC and re-birth as an independent, the Wave lost its identity. It no longer played familiar SEC rivals and no longer fought for conference championships every year. Biggest of all, it had no share of any conference’s television revenue.

After already suffering from its previous era of de-emphasis, Tulane, like many other schools, did not foresee the financial burden that athletic facilities, higher coaching salaries and Title IX would bring to college athletics.

However, aside from the additions of Arkansas and South Carolina to the SEC in 1992, followed by Texas A&M and Missouri in 2012, the biggest difference between the league now and when Tulane left is the amount of television revenue the conference generates.

In February 2022, the SEC distributed an average of $54.6 million per school, comprised of revenue from television deals, bowl games, the College Football Playoff and conference championships.

This includes seven of the 14 current SEC schools that have less SEC football titles than Tulane — Mississippi State, Kentucky, Vanderbilt, Arkansas, South Carolina, Missouri and Texas A&M. Ole Miss, another SEC school, has not won the conference’s football title since 1963, three years before the Green Wave departed the conference.

In fiscal year 2019, LSU’s athletic department generated a grand total revenue of $160,460,476, with $95,063,116 coming from football alone according to the U.S. Department of Education. By comparison, Tulane generated a grand total of $31,836,150 in athletics revenue in 2019, with $11,487,992 coming from football.

Furthermore, LSU’s football stadium holds 102,321 fans and generated $1.175 million in gross concession sales in general admission in a single game against Florida in 2019 and although the Tigers and Wave haven’t met since 2009, LSU holds an 18-game win streak going back to 1983.

Tulane has not fared much better in recent times against its other traditional SEC rivals, Auburn and Ole Miss. The Wave faced Auburn in the 2019 season and fell to the Tigers 24-6 and were later walloped 61-21 by the Rebels in 2021 while repping throwback SEC helmets.

This Saturday we are stepping back in time to our days in the SEC.

Welcome back, Greenie! #RollWave 🌊 pic.twitter.com/eBoI0plCxX

— Tulane Football (@GreenWaveFB) September 16, 2021

On top of everything else, Tulane’s athletic department was plagued with issues in the 80s and 90s. The university was a single vote away from disbanding its football program in 1985, then again in the early 2000s and its basketball program was shut down from 1985-1989.

Tulane’s non-football programs joined the Metro Conference in 1975, and when the Metro merged with the Great Midwest Conference in 1995 to create Conference USA, Tulane football was part of a league for the first time since leaving the SEC.

C-USA is nowhere near the SEC’s caliber, and the Wave competed against teams such as Louisville, Memphis, Southern Miss and East Carolina among others. The Green Wave saw success shortly after joining C-USA when they finished undefeated 12-0 in 1998, but finished the year ranked No. 7 due to a weak schedule and home attendance hovered around 38,000 per game.

In 2014 the Green Wave switched conferences, joining the American Athletic Conference where it still competes today, but its athletic recruiting is still limited by academic standards, making it more challenging for Tulane to compete with its peers.

Ninety years later in 2022, the landscape is shifting once again, and the amount of money in the sport will only continue to grow over time. Last year, Texas and Oklahoma announced that they will join the SEC and earlier this summer UCLA and USC announced their move from the PAC-12 to the Big-10. After the move, the Big 10 signed a record breaking 7 year, $8 billion-plus television deal. Meanwhile, the American Athletic Conference’s television deal, worth $83.3 million per year runs through 2031-32 and will pay around $7 million a year per school.

It is hard to tell what college football will look like in even the next five years, but it seems like the Green Wave will not be joining a new conference. With the latest moves in the SEC and Big 10, forget the Power Five. Today, we have the Power Two — and it seems very unlikely Tulane will be joining either of them.

Leave a Comment