OPINION | Hybrid classrooms are worst of both worlds

Hybrid classrooms come with a slew of technical issues

September 16, 2020

Since March, the COVID-19 pandemic has undoubtedly wrought havoc on the college classroom. Learning, in the traditional sense, is no longer feasible, a truth becoming more apparent by the day as Tulane University students carry on with their academic careers despite the challenges of adapting to new academic terrains. The solution to the pandemic’s academic interference at other institutions has been to conduct class completely online. Yet, Tulane has hopped on a different bandwagon: wildly inconsistent, eerily unfamiliar and inherently flawed hybrid, or “Tech-Enhanced,” coursework.

Hybrid classes were created to decrease the risk of spreading the coronavirus by thinning out in-person attendees during the week, supposedly guaranteeing fewer people in the same room and allowing more space within the classroom to social distance. Ideally, every lecture would be broadcast live for students unable to attend in person, allowing synchronous learning on any given day, leveling the access to information provided to those physically in the classroom and those at home.

This invention has essentially eliminated the need for the question, “Should we be going to classes in person or should we be taking classes online?” It responds, “Neither. You can have the worst parts of both.” And on this promise, it delivers.

A fundamental oversight in the creation of this plan was a lack of standardization. At times, it feels that there were no directions that accompanied its introduction to Tulane faculty. Instead of concrete and intentional science, it seems that every professor has chosen to interpret the meaning of “hybrid” in their own unique way.

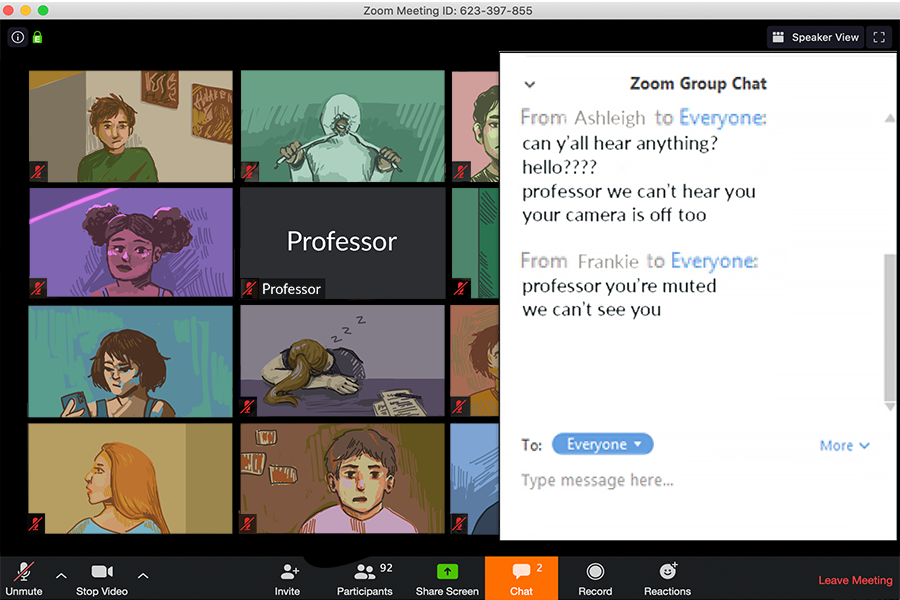

For some professors, the ‘hybrid’ experience entails expecting every student to attend class four times a week and includes paper, therefore introducing possibly contaminated syllabi, quizzes and tests. It is then a miracle when these same professors successfully broadcast their classes with both functioning video and audio.

On the other hand, for other professors, ‘hybrid’ means completely asynchronous learning at home, with the only live teacher-student interaction occurring for 15-minute intervals on Fridays via Zoom. Regardless of the actual efficacy of these approaches, it is indisputable that, despite their sharing of the ‘hybrid’ title, they are on completely different ends of a learning spectrum.

There is one aspect of this new type of learning that seems to be mutually agreed upon by every professor on Tulane’s campus, however. Academic expectations are nearly the same as they were pre-pandemic.

To succeed scholastically, students are expected to demonstrate the same level of understanding and competence as they were before the coronavirus. If students were provided with the tools to adapt to such unprecedented times, this might be a fair request. After all, Tulane students were given the opportunity to benefit from in-person instruction. Why should students get a pass if they are turning in assignments late or underperforming on tests?

First and foremost, the quality of education is not the same as it was, neither inside nor outside the physical classroom. Quite frankly, it is insulting to pretend otherwise. Inside, masks and distance measures, while required for good reason, inhibit simple comprehension of both the professor’s lectures and the students’ questions and contributions. This idea has been pushed even further in the temporary classrooms, in which the air conditioning units make learning nearly impossible.

Communication between both parties seems to be at an all-time low, with many students deciding that the struggle to get their question answered is not worth the effort.

From home, this result is imitated for the opposite reason; there is no way for a student to participate in class without their question ringing out from the surround sound speakers like the all-knowing voice of God. Those same students also rarely understand a single word from the professor who may forget to turn on their microphone, pace away from the podium or turn their head away from the computer to look at the white board.

Less tangibly, however, this expectation that ‘hybrid’ means a return to normal academic performance fails to take into account the stress of adapting to a public health crisis.

The pandemic has introduced new factors to students’ lives including regular testing, mandated isolation, increased responsibility for many on-campus jobs and decreased comfort in on-campus housing. While these factors help to ensure the safety of students, they come with their fair share of negative effects as well.

If executed properly, the hybrid classroom is a possible solution to the coronavirus learning problem. But, it doesn’t mean it’s the solution. These classrooms need serious adjustments as well as the recognition of their own shortcomings. This self-awareness could manifest in more flexibility on due dates or a more forgiving grading scale. It could also mean a complete departure and a return to 100% online classes.

Either way, there needs to be an institutional reflection of the qualitative deficiencies of hybrid learning compared to the pre-pandemic learning experience. Hybrid classrooms cannot be synonyms for traditional academic settings. Rather, they require new guidelines that reflect the unique predicament of Tulane students in an uncertain and precarious situation.

Student • Sep 21, 2020 at 11:17 am

Is the Tulane student body useful for anything accept constantly complaining? You people have no idea how privileged you are.